Right now is fish fry season! For many that observe Lent or live in communities that practice Lenten traditions, the Friday fish fry is a common practice in the 40 days that precede Easter. Growing up I was largely vegetarian/pescatarian (a hard thing to do surrounded by Texas BBQ) so I rejoiced this time of year where fish was plentiful and commonplace on menus. For others in my family this was the only time of year they eat fish. This time often brought up a lot of confusion in which fish to eat, or reservations about how “fishy” it was going to taste.

Fish can be downright confusing. For instance, there exist tradeoffs in nutrition and taste. Many fish are rich in Omega-3 fatty acids (the “good” fat), but this contributes to the “fishy” ocean taste, so more palatable fish have lower levels of omega-3s. There are also a variety of fish categories: wild caught, farmed (aquaculture), and shellfish. Becky Mansfield (2004) observed the debate over organic certifications for fish, and found that many views relate to the way fish elude classification. Her research highlights the ways people draw distinction between soil and water-based agriculture, and the troubles in defining ‘livestock’ or ‘wild’ and outside of producers’ control.

“Fish are different from everything else, but just what makes them different is not clear.” Mansfield, pg. 230

Fish also provide an avenue for examining connections between food production and sustainability goals. Much of the basis for expanding aquaculture is predicated on global fishery collapse. Aquaculture now makes up over half of the relative contribution of fish for human consumption (FAO, 2020). Sustainability is touted as a driver for expanding aquaculture production, however it also remains a point of contention against the industry. Aquaculture growth will increase demand for groundwater, and farm systems present contamination risks due to their large wastewater holdings. Growing fish on land still takes large amounts of marine inputs. Fish oils and protein for feeding raised fish have increased strain on wild stocks of input fish, like sardines and anchovies. Feeding fish alternatives, like plant proteins (ie. corn and soybean) encourage the problem of monocropping in the US and have nutritional compromises in the final fish product.

From a consumer standpoint it is extremely difficult to make purchasing decisions. As Michael Pollan made famous through “Vote with your fork,” food decisions are political and our choices can transform the food system. Julie Guthman (2007) provided a thought provoking account of subjectivities at play in these discourses, specifically in relation to the “epidemic of obesity.” She writes that Pollen and others “see themselves as morally superior to fat people in the sense that they characterize fat people as being short of subjectivity.” The core issue is that these types of food writers push a politics that is to do as they do. In Pollan’s case it is eating as an affluent thin white man.

In this vein I will resist telling you which food decisions to make, as is often the relation between academic “subject” writer and “object” reader needing intervention. Instead, I think talking about food should instead spur creativity and nuance in the ways we identify problems and propose solutions. Sustainability is vague and needs to be more specifically defined in conversations. When promoting “better” outcomes we should be explicit in the people considered in those politics. I want a food system that works for everyone- across race, class, ability, and gender.

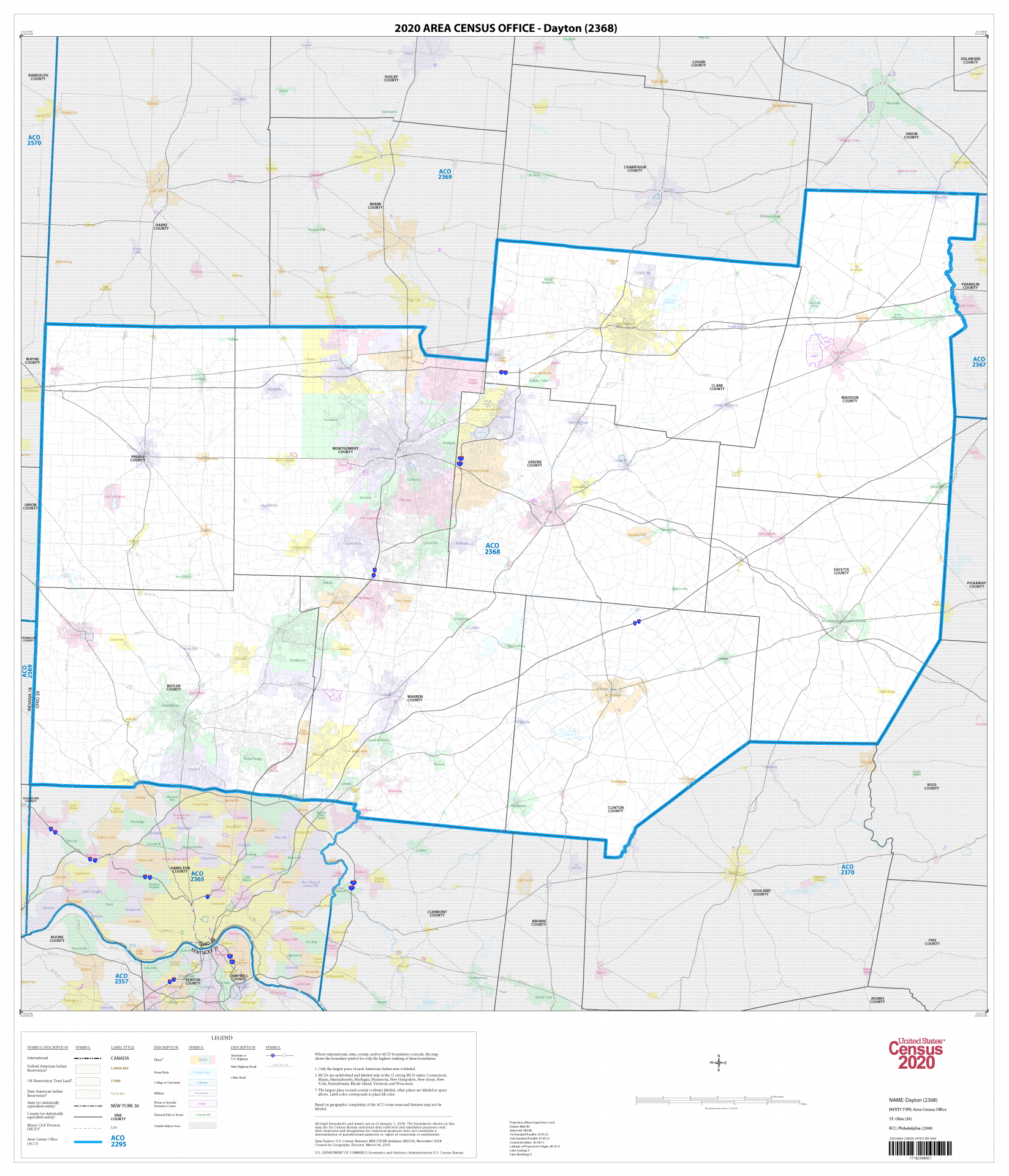

Finally, I will tell you what I have enjoyed in my own exploration into Midwest aquaculture. Fish offerings are much different here than when I grew up in Texas. Redfish isn’t on the menu but Walleye is. I was also surprised to see how many farms there were in the Midwest (see below). You can, in fact, get fresh live shrimp over 800 miles away from an ocean. I plan to continue researching Midwest fish over the next two years. If you have a fish farm- I’d love to stop by!

Map of aquaculture farm totals in the “Midwest” region. Data source: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Online_Resources/Aquaculture/index.php

Rebecca Chapman

Doctoral Student

chapman.751@osu.edu

Pronouns: she/her/hers

References:

FAO. 2020. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in action. Rome.

https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9229en

Guthman, Julie. 2013. “Can’t Stomach It How Michael Pollan Et Al. Made Me Want to Eat Cheetos.” Gastronomica 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2007.7.3.75

Mansfield, Becky. 2004. “Organic Views of Nature: The Debate Over Organic Certification for Aquatic Animals.” Sociologia Ruralis 44(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2004.00271.x

Pollan, Michael. “Voting With Your Fork” The New York Times “On the Table” Blog, May 7, 2006

https://michaelpollan.com/articles-archive/voting-with-your-fork/