Comparative anatomy is among our oldest scientific pursuits as humans, allowing us to differentiate between delectable and deadly, and helping us to make inferences about novel organisms, the threats they might pose, and the uses to which they might be put. Because the diversity of organisms in a museum collection exceeds that of any one location or habitat, museums are the premiere resource for comparative anatomy, allowing scientists to look at many individuals and many species, and to consider how form relates to function, evolutionary lineage, or location.

Fish Division collections manager Marc Kibbey has been using the Museum of Biological Diversity collections to study the anatomies of the feeding apparatus in suckers and minnows (order Cypriniformes). These fish (and several others) have a complex palatal organ (PO), first described by Aristotle from a common carp, that enables them to sort out food items from the inorganic material vacuumed from the bottom of the stream. Strongly analogous to a tongue, the organ is covered with taste receptors that send information to gustatory regions of the fish’s brain. The palatal organ’s motile structure is comprised of muscle, adipose and connective tissue, and fibers. Muscular expansion of the palatal organ pins food items to the gill arches allowing expulsion of the non-food items out of the gills. The food is then selectively moved back to the area between the chewing pad (CP) and the pharyngeal teeth for mastication.

This photograph is from Michael Doosey (2011), showing the head of a Sacramento Sucker with the operculum and gill basket removed, revealing the palatal organ (PO) and chewing pad (CP). The preparation of our skeletons uses dermestid beetles that would consume the muscular palatal organ, but the skeleton of the keratinous chewing pad remains.

Sacramento Sucker, northern and central California. Image from Fishbase.

The food of suckers is chewed, but not by teeth in the mouth: suckers have throat teeth instead of jaw teeth. These teeth are part of the gill apparatus, and differences in the shape and number of the teeth, and depth and breadth of the pharyngeal bones, help identify species and determine the types of food items they eat. Pharyngeal teeth are constantly replaced as they are lost.

The gill basket of a Northern Hogsucker, showing the pharyngeal teeth on the posteriormost gill arch.

Northern Hogsucker, Mississippi River and Great Lakes drainages. Photo by Uland Thomas.

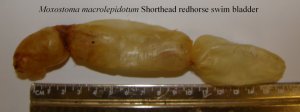

Other clues to the biology and ecology of fishes lie in the anatomy of their swim bladders. Morphological differences in size and shape, and number of chambers in the swim bladders vary between and can help identify the species. Size of the swim bladder corresponds to where the fish spends most of its time (suspended above or on the bottom). As with pharyngeal teeth, correspondence and consistency in the distribution of these features allows us to make inferences about the biology of new species.

The swim bladders of the two sucker species shown here are diagnostic for their genera in that redhorse swim bladders are three chambered while carpsucker species have two chambers. The Ostariophysi (group that includes the minnows, suckers, characins and catfishes) have larger swim bladders that enable them not only to more easily maintain position in the water column but also to more effectively detect vibrations in the water due to connection to the Weberian apparatus. While most of the sucker species do have large swim bladders their bodies and skeletons are rather heavy, suiting them to their benthic lifestyle.

About the Authors: Dr. Marymegan Daly is an Associate Professor in the Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology and Director of the OSU Fish Division. Marc Kibbey is Associate Curator of the Fish Division in the Museum of Biological Diversity.

I appreciate the effort Pututogel puts into security. Pututogel