The census data we use today is a symbol of American democracy. The U.S. Constitution states that “the actual enumeration shall be made … within every subsequent term of ten years, in such manner as they shall by Law direct” (Article 1, Section 2). After this historical point, the census has a brand new meaning beyond the mere means for the royalty or state to make their economic or political gains. Today, U.S. census data are commonly used for mapping and many other purposes. It is literally the textbook example of spatial data and applications in GIS and cartography education. Indeed, the U.S. census has empowered individuals and organizations around the world. A few simple clicks on an interactive map shown below, for example, will reveal some stunning pattern of spatial dynamics across America, even at a county level.

However, as useful and powerful as the census data are, shortcomings and challenges are also noticeable. Let’s start from a spatial perspective and ask ourselves this question: are census data safe? The following map comes from the dark side of using census data. It was made by Nazi Germany circa 1940, before the U.S. formally entered the Second World War. This map details the first and second generation of middle and western Europe immigrants in the United States, based on the publicly available data from the 1930 U.S. Census. It also has a label at the top left corner that reads “For official use only!” Its cartographic achievement aside, this map was used by the Nazi propaganda machine to strategically spend their war money to persuade the public opinion in the U.S. to avoid being involved in the war raging in Europe. Many believed such a campaign was successful to some extent. It is safe to say that, ever since then, the use of the census data and maps in today’s affairs, from political campaigns to social media disinformation to foreign meddling of our elections, is everything but the lack of imagination.

The arguably darkest moment of the U.S. census also came in the Second World War, when the census information used by the U.S. government directly led to the internment of Japanese Americans after the Pearl Harbor attack. So is it really provocative to ask will the census data, mapped or not, put us in danger? Will history repeat itself in the 21st century? Will another ethnic group become the victims? While the 2020 census eventually did not include citizenship questions, it should not be the time to celebrate. Instead, we should ask will such questions ever come back, and in what form? These issues may be beyond the scope of the census, but the census has been the vehicle that carries these issues.

Also from the spatial perspective, it is well known that census geographies are designed in a hierarchical fashion where the blocks are the smallest spatial units and from there we can aggregate to units such as block groups, tracts, and counties. Census tracts have been considered to be the relatively stable units for statistical analysis because by design they aim to have an ideal population of 4,000. But why should space be delineated in such a fixed and perhaps artificial way? What if we can re-arrange the blocks and come up with different kind of units that are compatible with the official tracts? This is a notoriously difficult task because there are an astronomical amount of ways to recombine the blocks. But if we test some algorithms on a manageable number of units, we can see how the world can be different. The two figures below show the result of such an exercise. It is clear that we can actually achieve a better set of spatial units where the population is more evenly distributed and more centered around the ideal size. Also, the new aggregated units show no significant spatial auto-correlation, which makes them more suitable for statistical analysis.

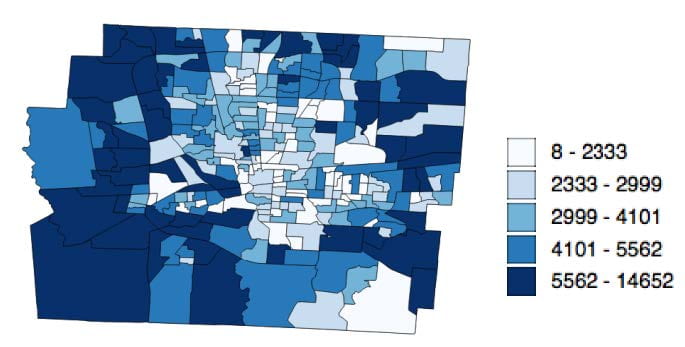

Population of the 284 census tracts in Franklin County, Ohio.

Population of the 284 new units that are aggregated using the 887 census block groups in Franklin County, Ohio.

Issues related to spatial units are not new and have been around in statistics and geography for at least more than a half century. Computational advances have made it possible to explore new and different approaches to spatial organization. The question is: how can we embrace such a new way of thinking about these statistical units? Should we even go down this rabbit hole where things will become constantly changing.

We can certainly read the history of the use of census data through different lenses. But, however we read it, we will find both bright and dark sides that are full of conflicts, betrayal, conspiracy, struggle, and promises. The world envies the richness of the census data available in the United States that dates back to the beginning days. From this perspective, I personally do see more promises than anything else, as the new century should be the time for us, the research community as well as the general public, to re-imagine what the census data could be.

Ningchuan Xiao, Professor

Department of Geography