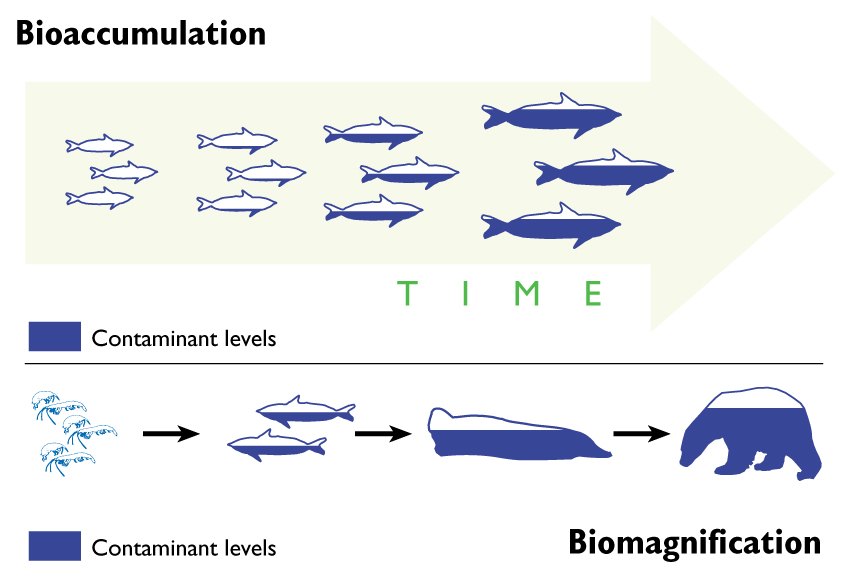

Mercury is the famous metal that is liquid at room temperature that was commonly found in old fashioned thermometers. While it is cool to look at in chemistry class, mercury is very toxic to humans as well as animals causing damage to your brain and nervous system. Mercury pollution in the environment is mostly as a result of industrial activity such as burning coal, releasing into the air, and then depositing in aquatic ecosystems in the form of methylmercury (Dietz et al. 2013). Methylmercury eventually finds itself in fatty tissues of aquatic species and builds up as it is consumed over its lifetime, which is described as bioaccumulation (Branco et al. 2021). This is why you often hear warnings from doctors to watch your intake of ocean fish in order to avoid excessive mercury intake.

While the melting of ice caps due to global warming is the primary concern for the conservation of polar bears (Ursus maritimus), accumulation of contaminants in its body are a close second. Polar bears are a top predator in the Artic region of the planet, their diets mostly consisting of fatty seals and fish. This diet rich in fat causes them to be exposed to extremely high concentrations of contaminants of chemicals such as mercury as it travels up the food chain (Routti et al. 2013). Studies suggest that this accumulation of contaminants will cause polar bears to have weakened immune systems, making them vulnerable to disease (Routtie et al. 2013).

Mother and cubs on a small ice floe, taken near Svalbard. Image courtesy of Russel Millner and National Geographic Your Shot (2021).

High levels of mercury, in particular, can have many negative effects on polar bears. The primary danger of mercury is the risk of neurotoxicity, which is when the nervous system is damaged by toxins in the brain and brain stem (Branco et al. 2021). This can result in an impairment of many brain functions, which can impact the success of hunting. Prolonged high levels of mercury toxicity can impair mobility and the senses and can even result in the death of the polar bear (Branco et al. 2021). Studies show that developing mammals’ growth is also impaired when exposed to high levels of mercury (Branco et al. 2021).

Data shows that mercury concentrations in Arctic animals have increased over the last 150 years, showing that human activity is likely to blame (Dietz et al. 2013). This shows how our carbon emissions are continually discovered to have additional negative effects on our planet. Polar bears are amazing animals and as this blog shows, our damage to the environment is hurting and will continue to hurt them if we do not take action.

References:

Branco, V., Aschner, M., & Carvalho, C. (2021). Neurotoxicity of Mercury: An old issue with contemporary significance. Neurotoxicity of Metals: Old Issues and New Developments, 239–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ant.2021.01.001

Dietz, R., Sonne, C., Basu, N., Braune, B., O’Hara, T., Letcher, R. J., Scheuhammer, T., Andersen, M., Andreasen, C., Andriashek, D., Asmund, G., Aubail, A., Baagøe, H., Born, E. W., Chan, H. M., Derocher, A. E., Grandjean, P., Knott, K., Kirkegaard, M., … Aars, J. (2013). What are the toxicological effects of mercury in Arctic biota? Science of The Total Environment, 443, 775–790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.11.046

Millner, R. (2021). Will There Be Ice When We Grow Up? National Geographic Your Shot. National Geographic. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from http://yourshot.nationalgeographic.com/photos/2348856/.

Routti, H., Atwood, T. C., Bechshoft, T., Boltunov, A., Ciesielski, T. M., Desforges, J.-P., Dietz, R., Gabrielsen, G. W., Jenssen, B. M., Letcher, R. J., McKinney, M. A., Morris, A. D., Rigét, F. F., Sonne, C., Styrishave, B., & Tartu, S. (2019). State of knowledge on current exposure, fate and potential health effects of contaminants in polar bears from the Circumpolar Arctic. Science of The Total Environment, 664, 1063–1083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.030