The Kellerman Displays for the 1903 Chicago Exposition

Most of the specimens at the Ohio State University Herbarium (OS) are tucked neatly into cabinets, not on display. But adorning one long wall are what at first glance look like pictures. Artfully arranged, with wood frames and a glass front, a close look reveals they are not paintings but are in fact real, once-living, plants and fungi.

The displays are quite pretty and they’re obviously rather old, but I never stopped to consider just how old they are, or how they came to be. A modern interpretive sign explains that they, along with four larger, more intricate panels of Ohio trees, were assembled for display at the World’s Columbian Exposition, a big world’s fair held in Chicago for six months in mid-1893.

At the top of each 18 x 22-inch panel is a printed heading “Flora of Ohio,” and beneath that, in ornate old-style penmanship, are the words “Prepared by Professor and Mrs. W. A. Kellerman.” William A. Kellerman was remarkably energetic and wide-ranging in his botanical interests. Making these panels was an appropriate hobby for a person whose life revolved around plants and fungi. An Ohio native born in 1840, he attended Cornell University for undergraduate studies and later received his Ph.D. from the University of Zurich, Switzerland. He taught at schools in several nearby US states before returning home to become OSU’s first botany professor and Chairman of the Department of Botany when it was formed in 1891. That same year, he established the Herbarium in a building aptly named “Botany Hall” that unfortunately no longer exists on OSU’s oval. Since then the Herbarium has moved twice, first to the also aptly named “Botany and Zoology” building (now Jennings Hall) and then to its present location as part of the Museum of Biological Diversity on West Campus (1315 Kinnear Rd.). While his principal research interest was rust fungus diseases of crops, Kellerman’s numerous works on the flora of the regions where he lived reveal an extraordinary breadth of knowledge. He wrote a guide intended principally for use by teachers entitled “Spring Flora of Ohio” (1895) and co-authored, beginning in 1894 and subsequently updated several times, “A catalogue of Ohio Plants.” Sadly, while Kellerman was on a research trip to study fungi in Guatemala, he contracted a fever (most likely malaria) from which he died in 1907.

The panels are an interesting snapshot of the flora of Ohio. While aesthetics and enthusiasm for particular plants may have played a major role in their selection by the Kellermans, the panels were indeed portrayed to fairgoers as indigenous representatives of our flora. As there have been substantial changes in the composition of our vegetation, especially for such pollution and disturbance-sensitive organisms as lichens, they arouse curiosity about the past versus present status of these organisms.

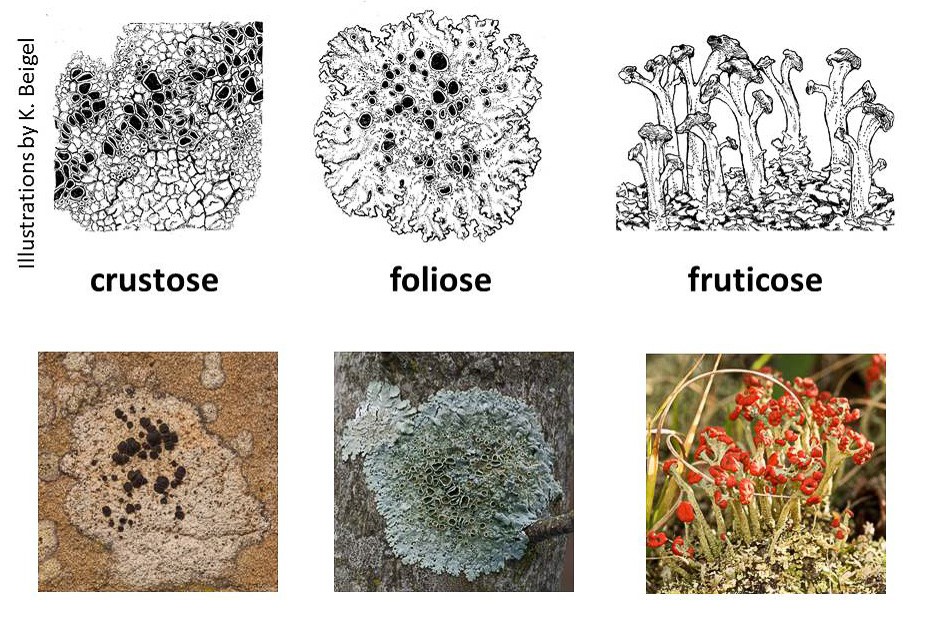

Lichens are dual organisms consisting of fungus plus alga. The algae are single-celled photosynthetic organisms. The fungus, which constitutes most of the body of a lichen, provides a home for the algae, usually in a layer just beneath the surface. Most lichens fall into one of three growth-form categories: (1) usually small “crustose” lichens that are tightly attached to the substrate and so don’t have a discernable lower surface; (2) small to medium-sized “foliose” lichens that are flattened and can usually be separated from the substrate, and (3) “fruticose” lichens that have a bushy shape, either standing upright from the surface they are growing on, or dangling off a tree branch or trunk. Most of the lichens in the panels are foliose species.

There doesn’t seem to be a strict organization scheme for the lichen panels; they’re not in alphabetical or taxonomic order, except that one panel consists mostly of crustose species, while the few fruticose ones represented are grouped together, sharing space with some foliose ones. I suspect that the paucity of fruticose types is attributable to the display method only being suitable for flat or readily flattened specimens.

Each panel includes 9 specimens, with handwritten labels. The classification of lichens has undergone substantial change in the past century and a quarter, hence many of the names written by the Kellermans are not in use today. Fortunately, an on-line database called “Consortium of North American Lichen Herbaria” lists specimen records for lichens residing in collections spanning the continent, and the site lists all the names by which a species has been known in the past.

The present distribution of lichens in Ohio is well described in The Macrolichens of Ohio by Ray E. Showman and Don G. Flenniken, published in 2004 by the Ohio Biological Survey, and distribution maps presented on the web site of the Ohio Moss and Lichen Association. The status of the lichens more broadly is set forth in a monumental book, Lichens of North America by Irwin M. Brodo, Sylvia D. Sharnoff and Stephen Sharnoff, published in 2001 by Yale University Press, along with an updated companion volume by Brodo published in 2016 by the Canadian Museum of Nature, Keys to Lichens of North America: Revised and Expanded.

One panel caught my eye. This is a group of mostly rather large foliose lichens, including several “lungworts,” members of the Lobaria –robust broad-lobed species found on bark.

Among the most easily recognized of all lichens, lung lichen, Lobaria pulmonaria, was once widely distributed across Ohio, but no more. All but one of the 14 county records for lungwort are pre-1945, with the other one record being sometime between 1945 and 1965. Extensive searching has failed to find lung lichen today.

Why is it lung lichen gone from Ohio? It’s probably due to a multiplicity of factors that prevailed during the late 19th, and early 20th centuries: air pollution and disturbance of old-growth forests. Now that conditions are better for it to grow, perhaps a lack of propagules is keeping it from reestablishing itself. While eventually a warbler or vireo might fly in from some north woods with a little piece of lungwort on its foot, this might be a good candidate for a deliberate reintroduction.

This is what lungwort looks like, growing on a tree in Maine. It’s a beautiful lichen and that just might still be growing in in a bottomland forest somewhere in Ohio, or it might soon return. Keep an eye out for it the next time you go hiking!

About the Author: Bob Klips is Associate Professor Emeritus in the department of EEOBiology at The Ohio State University. He currently assists with moss and lichen databasing in the OSU herbarium. His research focuses on bryophyte ecology.

About the Author: Bob Klips is Associate Professor Emeritus in the department of EEOBiology at The Ohio State University. He currently assists with moss and lichen databasing in the OSU herbarium. His research focuses on bryophyte ecology.