Working with small organisms such as mites presents some interesting problems. One of those is getting folks interested in just thinking about something they usually cannot see. Of course a few mites are big enough to see and critters like ticks, velvet mites and water mites do enjoy some “popularity”. But for most mites we have only fairly bad photographs of crushed specimens on slides (often good for seeing specific characters, but horrible for outreach). Without nice images, we can still go for gross (I do admit that I occasionally enjoy going that route), with disgusting images of humans with scabies (Sarcoptes scabiei), or sad looking plants covered in spider mite silk, but it is not the same. And it really does not do much for improving the image of mites. Plus, most mites do not do any significant damage. So how should we present the “real” mites?

Let’s start with the high-tech approach.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was the first good option. Because of the high depth of field, SEM gives very nice, 3-D images at very high magnification. It works well for highly sclerotized mites (oribatid adults, uropodids) but it is less successful with small, soft-bodied species because most SEM techniques require critical point drying, which makes those soft bodied mites shrivel into ugly blobs. Using live mites can alleviate that problem but (a) most SEM operators do not like it (it introduces humidity into the machine and may damage it) and (b) mites are often not cooperative. As a beginning graduate student I had the option of putting some live sarcoptid mites in an SEM. The specimens were on sticky tape and everything looked great as the SEM got close to vacuum. However – there is always a “however” in these stories – just before we could get our first images the last of the great looking mites managed one more spurt of energy, and fell over, exposing nothing but its sticky stuff covered underside. That took care of my hopes for great pictures.

Low Temperature SEM (LT-SEM), uses liquid nitrogen to flash freeze the mites (no critical point drying), allowing views of live mites frozen in time. This completely bypasses the shriveling problems of standard SEM with stunning results. The folks at the USDA in Beltsville, MD, have generated some beautiful images of plant feeding mites. Sam Bolton, graduate student in acarology, worked with them to get the images of his “dragon mite”. Add some color (based on images of the mite taken before going into the SEM) and we end up with poster-worthy pictures.

Even LT-SEM has limitations, as we can only see surface structures. We are overcoming that limitation by using confocal laser scanning microscopy. With this technique you can also see internal structures, and with the right software, you can construct 3-D images that can be sliced any way you wish. Not quite as detailed as Synchroton X-ray microtomography, but that technique requires a particle accelerator the size of a football field, and at this point only one (in Grenoble, France) seems to be set up to handle images of mites. Confocal microscopy is great for research, but 3-D printing of the models also makes for excellent teaching tools (or gift store items).

Of course all of those techniques require highly specialized and expensive equipment. For day-to-day use we use an automated compound microscope and image stacking software to generate images that are both relatively detailed and retain some color. These tools finally allow generation of well-focused detailed images of very small organisms and structures. Unfortunately we do lose some of the 3-D effects in the process of image stacking, but on a good day, these images are publication quality.

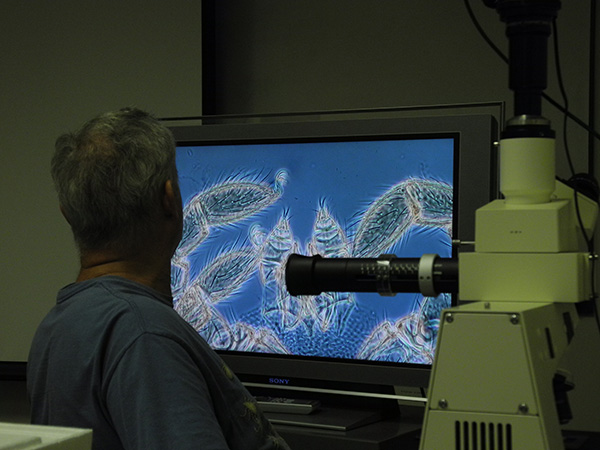

For more hands-on displays, mites can be viewed on a 40 inch TV-screen using a video camera connected to a compound or dissecting microscope. This is wonderful for teaching (6-12 people can all watch what you are seeing in the microscope), research (sometimes the image on the TV is more detailed than the one you get through the eyepieces of the microscope itself), and of course outreach. We use that set-up at the annual Museum Open House to show live mites in detail.

With enough technology, mites are coming out of the deep and dark, and into the light, where they of course belong. We are slowly generating more high quality images and making them available through the collection database. Check it out, the small can be beautiful.

About the Author: Dr. Hans Klompen is professor in the Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology and Director of the Ohio State University Acarology Collection.