The second country I visited for my study abroad tour was France. On Saturday, May 14th we took a ferry across the English Channel from Portsmouth, England to Caen, France. Our journey began here because of the historical significance of this area in 1944 and 1945 when the Allies launched the D-Day invasion at Normandy beach. We stayed in a small town named Bayeux. This is a humble town is centered around a cathedral that was built in the medieval times. Our main excursions while here were to museums and monuments in and around Omaha and Utah beach, which are the locations where American forces began the Normandy invasion. It was an incredibly moving experience to stand on the beaches where men gave their lives in order to help liberate Europe from Nazi control. I was particularly moved by a few specific experiences during my six-day stay in Bayeux. These experiences led me to get to know two people in very different ways. One was an owner of a café in Bayeux. The other was a soldier who died on June 6, 1944.

This small town was a change of pace after being in a city like London. The only way to travel around town was to walk. There was one main street and one grocery store. However, the town did not disappoint with the number of eateries and cafes. They lined most of the little streets. During my stay, I became particularly fond of a small café named Au Georges II. I went there frequently to get a Crepe with Nutella on it (tastes as good as it sounds). After a couple of days, I befriended the owner of this shop. I learned that his name is Jacques. Despite the obvious language barrier (he only spoke French and four years of high school Spanish didn’t really help me in France), I said hello to him every day I passed the café. On our last day in Bayeux, I was able to memorize a few sentences and give him a small gift.

This unlikely friendship is symbolic of what it was like to live in small town France. It had a feel unlike the large cities that we will be spending much of our trip in. It was a more relaxed pace and it was easy to feel at home. At the same time, this was nothing like the suburban lifestyle I have become accustomed to in the United States. Everybody walked to the outdoor shops and restaurants that were located along the river that ran straight through the town. The biggest concern as a tourist in Bayeux was whether or not the wifi would work (it usually didn’t). This peaceful town with beautiful architecture was a great change of pace for a group that also went to London and Paris.

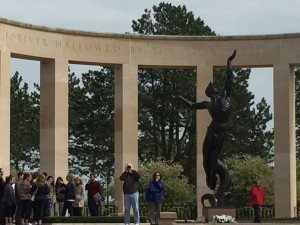

In addition to my stay in Bayeux, another big part of this site was the cemeteries we visited. In total, we visited three cemeteries: a German cemetery, a British cemetery, and an American cemetery. They each held the graves of soldiers who were killed during the Normandy campaign. It was stunning to be at both the places soldiers fought and the places they were laid to rest. I was particularly struck by the American cemetery. The cemetery is located just beyond the sands of Omaha beach, where the bloodiest fighting took place on D-Day. We began by placing a flag at the grave of twelve Ohio State students and faculty that died during the Normandy campaign and are buried in that cemetery. After this, we were given time to look around the grounds where 9,387 young men were buried. Time to pay our respects. Time to reflect. Time to contemplate. The rows and rows of crosses made it easy to yearn to know the stories of each individual soldier represented by each gravestone. This really hit me during my time alone at the cemetery. I wanted to know about each man, or at least think about who he was. When this thought hit me, I immediately walked down a row and stopped at a random grave to contemplate and gather my thoughts.

I don’t know Private First Class Fred W. Plumlee. I don’t know where he was when he died in combat on June 6, 1944. I don’t know where he lived in Georgia, what his family was like, or what he wanted to do with his life. All I know is what is engraved on his gravestone. A simple google search did not lead to anything definitive about this man. All I know is that his grave was in the exact spot where I stopped to spend a half an hour contemplating individuality in World War II. Though he is just a small grave in a sea of thousands of gravestones, he was still a person. I thought about what his dreams may have been, what his past was, and who the people were that he loved. Though I can’t answer any of these questions, I thought about who he might have been and considered whether or not he had anything in common with me. It was here that I reached a great understanding. Though we can’t know the story of every soldier who died in World War II, that’s not the part that matters. What matters is that we recognize that behind each gravestone is a unique man who deserves to be recognized as such. Though I couldn’t and think at all 9,387 graves, I did stop at one. And that made all the difference.