Uzbekistan has a total area of 447,400 square kilometers ranging from the Hazrati Sulton Peak at 15,233 feet (4,643m) above sea level to the depths of Sariqamish lake at 39 feet (12m) below sea level. It is about the size of Sweden and its territory is larger than the State of California. It is home to over 33 million people today.

Hazrati Sulton peak (view from Tajikistan)

Hazrati Sulton peak (view from Tajikistan)

Uzbekistan has twelve different provinces: Andijon, Bukhoro, Farghona, Jizzakh, Khorazm, Namangan, Navoiy, Qashqadaryo, Samarqand, Sirdaryo, Sukhondaryo, and Tashkent. Each one has its own unique culture and geography. Before moving to the next part of this module, take a few minutes to locate each province (in Uzbek “viloyat”) on the map provided below:

In this section, we are going to take a virtual tour of some of the diverse environments of Uzbekistan. After that we are going to learn about climate change in Uzbekistan and some of the modern environmental issues facing this beautiful country today. A glossary of key terms is provided at the end.

Our first stop is the Chimgan mountains outside of Tashkent, Uzbekistan’s capital city.

The Chimgan mountains are a famous tourist attraction, with world-class skiing in the winter. In addition to some more moderate routes, Chimgan also has “wild routes,” which are only available by way of a helicopter drop off and can be as long as 7 kilometers (about 4.3 miles). The Grand Chimgan peak (3,309 meters) and Small Chimgan peak (2,100 meters) are both fully covered in snow during the winter.

Chimgan during the winter of 2010 (photo by Pitirimov via wikicommons)

Chimgan during the winter of 2010 (photo by Pitirimov via wikicommons)

Heading to the southeast from the Tashkent region we arrive in the Ferghana valley. Famous for its blood sweating horses since the first century BCE, the lush valley surrounded by mountains has been a key environment in Uzbek history.

Ferghana Valley (Photo by Advantour)

Ferghana Valley (Photo by Advantour)

We now head to the southwest. Our next stop is the Zarafshan State Nature Reserve, located in the Samarkand region. It is named after the Zarafshan “spreader of gold” river.

The Zarafshan reserve (qo’riqxona) was founded in 1975 with the intention of saving the endangered Zarafshan pheasant as well as rare plant species. The park is also home to twenty-six different species of freshwater mollusks, including two endangered species, the colletopterum sogdianum (in Uzbek so’g’d tishsizi “the Soghdian toothless”) and the daryo savatchasi (“the river basket maker”). This reserve also preserves a rare example of the unique Tugay landscape.

Traveling down to the south, our next stop is the Sangardak waterfall in Surkhandarya region’s Sariosiyo district.

(Photo by Jonibek Kuzimurodov)

(Photo by Jonibek Kuzimurodov)

Now watch this video to see more of the nature of the Surkhandarya region and listen to the Uzbek language explanation.

Another attraction of the Surkhondaryo district are the ancient sycamore trees. Many of these trees are around a thousand years old and have become Sufi shrines over the centuries. In modern times, they have been used for other purposes as well. One of these trees was used as a school in the early twentieth century and then as a village administrative center in 1920, and then as a cavalry regiment’s library in the 1930s, and finally as a village shop.

Sycamore tree in the Surkhondaryo province of Uzbekistan, original photo by Yulduz, Alisher’s sister (2020)

Sycamore tree in the Surkhondaryo province of Uzbekistan, original photo by Yulduz, Alisher’s sister (2020)

Here are some photos from inside this tree:

original photos (2020)

Follow this link for a quick overview of sycamore trees in Uzbekistan: https://edgeofhumanity.com/2018/01/31/sycamore/.

Follow this link for a virtual tour of the inside of one of the trees: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FND3nlCNDhE.

We’ll now travel northwest until we reach the Qyzyl Qum “red sands” desert. It’s a big contrast with the mountains and valleys of eastern Uzbekistan.

The Qyzyl Qum desert (photo by Noelia)

The Qyzyl Qum desert (photo by Noelia)

The view from camel trekking in the Qyzyl Qum

The view from camel trekking in the Qyzyl Qum

Climate Change and Global Warming in Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan’s climate is continental. This means that it is affected by circulation patterns that originate in the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean and then flow across the Eurasian continent. The majority of the country’s water comes from rain and snow falling in the mountains during the winter and spring.

Uzbekistan, and Central Asia more broadly, have interacted with natural climate change events throughout earth’s history. A stalagmite record from the Ton cave, in the Surkhondaryo province, provides a record of the natural fluctuations in climate over glacial time scales (tens to hundreds of thousand of years). Since the end of the last Ice Age, around eleven thousand years ago, Central Asia’s climate has fluctuated between periods of warm and dry conditions and periods of cold and wet conditions.

These natural fluctuations in the earth’s temperature during the Holocene epoch were caused by periods of increased volcanic eruptions and decreases in the energy coming from the sun. More volcanic eruptions and less solar energy caused periods of global cooling. On the other hand, periods of decreased volcanic activity and stable solar energy cause natural increases in average temperatures.

During globally warmer periods, winter westerly Atlantic precipitation was drawn towards the north of Eurasia, which made Central Asia (and what is today Uzbekistan) drier. However, periods of colder global temperatures pushed this same flow of Atlantic precipitation to the south making Central Asia wetter, famously during what scientists call the Little Ice Age (roughly 1420-1825 CE). A recent study of temperature histories recorded in tree rings from the Pamir region (upriver from Uzbekistan, in Tajikistan), published by Polish climatology researcher Magdalena Opała-Owascarek, shows significant cold periods during the Little Ice Age, especially during the periods 1450-1650 and 1750-1790. These records also record a cold spike in response to the Tambora eruption in Indonesia in 1815. A separate study, based on a synthesis of twenty-one different climatic records, including historical documents and bubbles of compressed historical air trapped in ice-cores, shows that the colder temperatures coincided with increased moisture during the Little Ice Age.

These changes occurred at a much slower speed than the rapid human-caused climate change we are experiencing today. However, historical warm periods especially from 50BCE to 400CE and from 800 to 1200 CE, show that warmer global temperatures bring a drier climate to Central Asia.

Since the turn of the twentieth century, we have begun to see the impacts of modern human activity both on the ground and on the atmosphere. In what is today Uzbekistan, rivers were diverted and overexploited for cotton growing during the Soviet period as part of an economic policy that was based on misunderstandings of Central Asian ecology left over from the Russian imperial period.

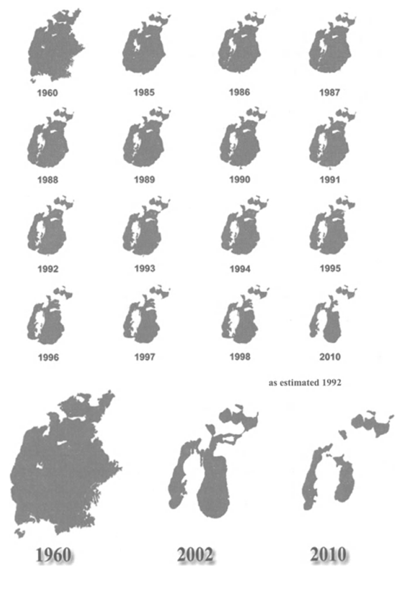

This policy changed the water balance of Uzbekistan, increasing ground-level aridity especially in the non-mountain regions. The drying up of the Aral Sea since the 1960s was a direct result of these policies. Now watch this video from NASA showing the transformation of the sea over the past two decades: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/world-of-change/AralSea.

Land water masks estimated from satellite imagery by Ressl and Micklin (2004): 80

Land water masks estimated from satellite imagery by Ressl and Micklin (2004): 80

Google maps image of the Aral Sea from November 2020

Google maps image of the Aral Sea from November 2020

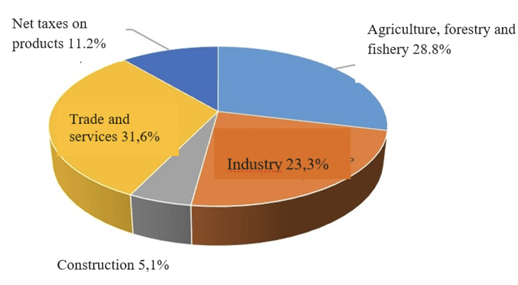

Global warming caused by the burning of fossil fuels also plays a role in this increased aridity on the ground, as less water is transported inland from the North Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean. Human-caused global warming is already influencing agriculture in Uzbekistan. A 2010 report from the World Bank, working in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources of Uzbekistan, found that approximately 34% of the country’s population was employed in agriculture and 23% of the country’s GDP comes from agriculture. This same study found that over 85% of Uzbekistan’s cropland is irrigated, which suggests that changes in overall temperature and annual rainfall over the next few decades will directly impact the economy. Just like in the US.

Uzbekistan’s economy in 2018 by sector

This report also predicted that the mean annual temperature will increase by between 1.9 and 2.4 degrees Celsius (3.4-4.3 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2050 with the greatest warming occurring in the winter and spring. (More recent studies predict up to 7 degrees Celsius of warming in mountain regions by the end of the century if there is no global mitigation, a scenario referred by climate change scientists as RCP8.5.)

With the predicted increase in precipitation occurring during the summer months, when evaporation is at its highest, the overall change in total water availability after evapotranspiration will lead to a more arid climate.

These ecological changes have economic consequences. A 2016 study, found that the economic costs of land degradation changes in Uzbekistan from 2001 to 2009 have reached as high as 0.85 billion USD annually (by today’s exchange rate that’s just short of nine trillion Uzbek so’m). Another study from that same year estimated that 0.3 billion USD of that cost is caused by deforestation alone. Senior Researcher at the University of Bonn and Coordinating Lead Author for the IPCC special report on Climate Change and Land (2019) Alisher Mirzabayev emphasizes that farmers in Uzbekistan are already experiencing ecological shocks from human-caused global warming.

Glossary

Viloyat — a province of Uzbekistan, kind of like a state in the US. Uzbekistan has twelve provinces, viloyatlar.

Tugay Landscape — a landscape characterized by vegetation, forests, bush communities, and meadows relying on water coming from rivers or underground water systems in the desert and semi-desert regions of Asia.

Glacial Time Scales — also called “orbital time scales”, cycles of hundreds of thousands of years, when earth’s climate was driven by changes in the shape of its orbit around the sun, the angle of its axis and the wobble of its axis, also called the Milankovich cycles.

The Last Ice Age — a period of wide-spread glacial expansion from around sixty thousand years ago to thirteen thousand years at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, with the coldest period at roughly 20-25 thousand years ago, a time called the Last Glacial Maximum.

The Holocene epoch — the geological period between the end of the last “Ice age” around 11,700 years ago and human-caused warming starting around 1850.

The Little Ice Age — a period of global cooling caused by volcanic eruptions and solar minima, around 1420-1825 CE.

Evapotranspiration — the sum of evaporation from the ground to the atmosphere and transpiration from plants (in other words plants “breathing,” well technically transpiring, water vapor into the atmosphere).

Suggested Learning Activity

Despite the challenges of human-caused global warming, there are ways to mitigate the global crisis! Now watch this video about land use in the Khorazm region of Uzbekistan. Based on what you learned from the video complete the following three tasks:

- Write down on a sheet of paper one of the environmental problems facing this part of Uzbekistan.

- On that same piece of paper, write down one of the suggested solutions that the video talks about. Choose whichever one you think will be most effective!

- Share your results with your fellow classmates and discuss possible future courses of action we could take.

References and Additional Resources

- To learn more about Uzbekistan’s natural attractions go to the National PR-centre’s website: https://uzbekistan.travel/en/c/nature-of-uzbekistan/

- (This center is part of the State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan for Tourism development.)

- Basic travel information about nature in Uzbekistan: https://centralasia-adventures.com/en/sights/uzbekistan/natural_sights_of_uzbekistan

- A travel guide to the Qyzyl Qum desert: https://caravanistan.com/uzbekistan/center/kyzylkum/

- A video by the Vagabrothers about the Aral Sea: What Happened to the Aral Sea? | Travel to Uzbekistan’s Worst Disaster

- A summary of Central Asian climate history: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-00728-7_1

- A summary of Aral Sea research: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783540882763

- For an account of the modern Aral Sea and irrigation history, see Maya Peterson’s masterful Pipe Dreams: Water and Empire in Central Asia’s Aral Sea Basin Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- For more about Central Asian climate history: https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-285

- For more on water in Central Asia see: https://water-ca.org

- A discussion of land degradation in Central Asia: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-19168-3_10.pdf

- More about the village of Sayrob: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Amr74YVfxzk

- A resource about ecology in Muslim culture: https://muslimheritage.com/category/environment/ecology/

- An article about Ibn Sina and the earth sciences: https://muslimheritage.com/ibn-sina-development-earth-sciences/

- A discussion of Islamic scholars’ views on evolution: https://muslimheritage.com/islamic-foreshadowing-of-evolution/

- An online resource for the Milankovich cycles: https://cimss.ssec.wisc.edu/wxfest/Milankovitch/earthorbit.html

- An assessment of organic agriculture in Uzbekistan: http://www.fao.org/3/i8398en/I8398EN.pdf