[This site went public in August 2017. with continued additions and editing. Comments are encouraged – if a topic seems to be missing or restricted, we welcome suggestions or contributions. We hope the site is a useful resource for the research community

[This site went public in August 2017. with continued additions and editing. Comments are encouraged – if a topic seems to be missing or restricted, we welcome suggestions or contributions. We hope the site is a useful resource for the research community

SIGNIFICANT RESEARCH NEWS: (we highlight a recent report that we deem of general interest; earlier entries can be found on a subpage).

The journal Tropical Medicine and Infectious Diseases released, in May 2018, a special topics issue “The Past and Present Threat of Rickettsial Diseases” which contains several papers focused on scrub typhus.

[July 25, 2018] – Fleshman, A. et al. 2018 – Comparative pan-genomic analyses of Orientia tsutsugamushi reveal an exceptional model of bacterial evolution driving genomic diversity. Microbial Genomics 2018; 4. — compared 40 genomes of O.t. from geographically dispersed areas. Confirmed patterns of extensive homologous recombination likely driven by transposons,

conjugative elements and repetitive sequences. High rates of lateral gene transfer (LGT) among O. t. genomes appear to have effectively eliminated a detectable clonal frame, but not the ability to infer evolutionary relationships and phylogeographical clustering.

[May 12, 2018] Batty,M.E. and Batty M,E. of OXFORD UNIVERSITY, Wellcome Centre for Human Genetics have released on GenBank the complete sequences of eight isolates of O. tsutsugamushi. These strains include Karp, Kato, Gilliam, FPW1038, TA686, TA763, UT76 and UT176. The importance of this release is that it represents high-quality genomes generated using PacBio single molecule long read sequencing. This procedure allows the gene order to be determined with high confidence despite the presence of large numbers of repeated elements within the genomes. Sequences available in GenBank. citation: Batty EM, Chaemchuen S, Blacksell S, Richards AL, Paris D, Bowden R, et al. (2018) Long-read whole genome sequencing and comparative analysis of six strains of the human pathogen Orientia tsutsugamushi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12(6): e0006566. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006566

THE HISTORY OF SCRUB TYPHUS

Scrub typhus, tsutsugamushi disease, or more accurately, chigger-borne rickettsiosis is an acute, febrile illness of humans caused by infection with the bacterium Orientia tsutsugamushi following the bite of infected Leptotrombidium sp. mite vectors.

Like many infectious diseases, the early recorded history of scrub typhus is somewhat sketchy, although some early accounts appear to describe the disease. What was possibly the earliest published account of scrub typhus was from the Ming Dynasty in China during the 3rd century A.D. Symptoms associated with scrub typhus were first described in China in 313 AD. According to a Chinese “Material Medica,” as reported by Li Shih-Chen in 1885, this early description was in a patient with disease symptoms consistent with scrub typhus The vector of scrub typhus may also have been described in China in the first millennium. Small red insects, possibly the red chiggers of scrub typhus, were described in the account from 313, while a Chinese medical book in the 6th century described a “sand louse” vector found along river banks (Kawamura, R. 1926).

The first modern report of the disease appeared in Japan in 1879 (Bälz & Kawakami), where it was labeled ‘tsutsugamushi fever’. This report, from the Niigata Prefecture, described scrub typhus as “river” or “flood fever”.

There were reports both within Japan and in other regions within what had become to be called the “Tsutsugamushi Triangle,” including Sumatra (1902), the Philippines (1908), Queensland, Australia (1910), Vietnam, and Malaya (1915). Primarily Japanese and British investigators were involved with scrub typhus research during the 1920’s and 1930’s prior to World War II. In the decades between the wars Japanese scientists were heavily involved in characterizing the disease including identification of the etiology (Hayashi, N. 1920). In fact the actual agent of the disease, then named “Rickettsia orientalis” by Japanese scientists and now known as Orientia tsutsugamushi was further described in a series of studies by Nagayo, et al. from 1921 to 1931 (reviewed in Oaks et al., 1983).

About the same time British scientists also became involved with diagnosis and characterization of the disease. Misdiagnosis of scrub typhus in that era was common, and to this day diagnosis can be difficult. Generalized signs and symptoms of scrub typhus include fever, headache, and rash, which are also common to several other febrile illnesses such as dengue, typhoid fever, and malaria and can confuse the diagnosis. Even the tell-tail eschar, often associated with the bite site of the infected chigger, is present only about half the time. In fact it wasn’t until the 1930’s that scrub typhus had been clearly differentiated from other typhus fevers. British scientists working at the Malayan Institute for Medical Research (IMR) in Kuala Lumpur were able to definitively separate typhus-like fevers into distinct entities, the form known as urban, endemic or murine typhus, from rural or scrub typhus (Maxcy, 1948) .

Research on scrub typhus accelerated rapidly during World War II, when military operations occurred in areas of endemic scrub typhus in Eastern and Southern Asia and the islands of the Western Pacific. Based upon prior experiences during the “Great War” or First World War, the United States of America Typhus Commission was constituted early in the war, 1942, in anticipation of the expected impact of epidemic typhus. The Americans would soon discover the impact of another rickettsial disease in military actions primarily in the Asia-Pacific Theater of Operations.

THE PRIMARY AGENT OF SCRUB TYPHUS

O. tsutsugamushi is a member of the rickettsiaceae, within the alpha proteobacteria. It is an obligate intracellular bacterium. O. tsutsugamushi differs from the members of the genus Rickettsia in cell wall structure, as well as by significant genetic differences. The size of the genomes of different isolates of O. tsutsugamushi (in nucleotides) appear to be slightly in excess of 2Mb (compared to genomes of 0.7-1.3 Mb for various members of Rickettsia). This difference in genome size is accompanied by an increased number of genes in Orientia compared to Rickettsia. (Information is expanded on another page). Recently, additional agents have been identified in dispersed localities far from the “Tsutsugamushi triangle” of Asia/Western Pacific rim.

SCRUB TYPHUS – THE DISEASE

The disease is characterized by lymphadenopathy, high fever, and a rash. Often headache, anorexia or general apathy may occur. The rash is accompanied by an eschar in ~50% of individuals (reference needed).

Individuals usually have a history of exposure to areas in which the disease and its vectors (trombiculid mites) are endemic. It is transmitted by the bite of infected chiggers particularly of the genus Leptotrombidium. Further information is available in several reviews (1) (2).

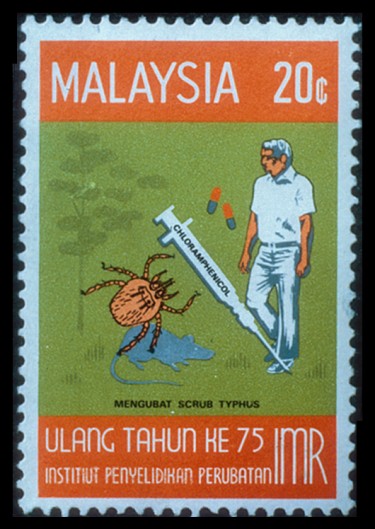

The clinical and laboratory features of scrub typhus are notoriously nonspecific. Physicians often misinterpret early clinical signs, although clinical diagnosis has improved markedly over the last 30 years (see lecture notes from George Lewis). The single most useful diagnostic clue is the eschar, but this may appear in only about 50% of infected individuals. When an infection is recognized early, and correctly diagnosed, scrub typhus is usually easily treated with chloramphenicol or tetracycline. The first successful treatment of scrub typhus by antibiotics was accomplished by a multinational team in 1948, using the drug chloromycetin. Information on this treatment of scrub typhus is given on the accompanying page on “Antibiotics“. Mortality rates may exceed 5% in untreated individuals, and may still be 1% or higher when antibiotics are used. There is currently no effective vaccine available.

Stamp issued by Malaysia in 1976 as part of a three stamp issue celebrating the Institute of Medical Research. The stamp shown at left commemorated the first successful treatment of scrub typhus by antibiotics in 1948.

Although scrub typhus is usually successfully treated with antibiotics, there appears to be some evidence of antibiotic resistance, especially in areas of Southeast Asia, although the basis of resistance remains to be elucidated. (Watt, 1996).

GEOGRAPHY

The primary geographic range of infection is a 13,000,000 sq km region along the Asia-Pacific rim (see page on geography) but recently cases have been reported is such disparate regions as the Arabian peninsula, Chile, Peru, and West Africa. Disease in these dispersed localities may not be due to infection by O. tsutsugamushi, but might potentially be attributed to newly described or even undescribed members of the genus Orientia. Further details are presented on another page.

DIAGNOSTIC METHODS (further details on a subsequent page)

Diagnostic methods based on serological approaches resulted in more accurate ways to identify scrub typhus infections and separate them from other fevers of unknown origin. By the end of the Twentieth Century, advances in molecular biology had provided new tools for increasingly sensitive and accurate study of the disease, its agent and its vectors. Details on serological diagnostic methods are detailed on a subsequent page.

Early approaches at identifying or phenotyping virulent Orientia strains included mouse cross-neutralization assays, complement fixation tests and, later, direct and indirect fluorescent antibody typing, and strain specific monoclonal antibody typing (see Kelly at al., review, 2009). These methods have proven to be confusing and somewhat difficult to reproduce. Nevertheless, they indicated that the global population of O. tsutsugamushi is characterized by significant variation in the microbial components that lead to serological responses by infected humans.

Since the early 1990’s, genotypic based methods have become available that allow a more detailed identification of isolates of the organism. Information about the genetics/genomics of Orientia are presented on another page.

THE OBJECTIVES OF THIS SITE

In developing this website we are attempting to build on work that was previously published in a review paper coauthored by the contributors to this site. We hope to provide basic information on the epidemiological occurrence of scrub typhus, on aspects of its serological and genetic variation, on aspects of the epidemiological and genetic history of scrub typhus research, on what has become recently known about the genomes of members of Orientia, and on the geographic distribution of genetic types of Orientia, as defined by the DNA genotypes at various loci that have been accumulated in the international DNA databases (GenBank and DDBJ). We hope that the information that we will provide is useful to the international research community working to understand and treat scrub typhus throughout its distribution.

———————————————————————————–

Concerning this web site:

January 2018 – present: The site is still “under construction” with significant additions expected. See the updates page for the most recent additions or changes.

This site is a joint effort by researchers at The Ohio State University (Paul Fuerst and Daryl Kelly) and members of the Viral and Rickettsial Diseases Department, Naval Medical Research Center (Allen L. Richards).