When someone decides whether to read something or not, including a blog post, they look at the title and determine whether it seems of interest. National income accounting (taxes, spending, the deficit, etc.) is not the most glamorous title in the world BUT maybe the part about money grabbed your attention. Conventional wisdom is that money is the root of all evil, but Mark Twain said it best when he wrote, “Money is not the root of all evil; the LACK OF MONEY is the root of all evil.” And besides, people perk up when the subject turns to money.

Humor aside for a moment, the topic of the deficit and the debt is extremely important. Remember back in 2011 and 2013 when the Congress of the United States seriously threatened to refuse to raise the debt ceiling? Remember the “fiscal cliff” of late 2012? These events caused shock waves to drive through the entire world and almost led to a catastrophe that would have severely damaged the world economy and cost hundreds of millions of people their jobs. And I am not talking about people in the financial sector. I am talking about people in all lines of work – people in communities throughout the United States. You want to talk about community development? Extension does a great job in this effort, but national recessions always rob communities of resources they need in order to thrive, despite the best efforts of elected officials, business people, or outreach educators. That is one of the reasons why I, as a faculty member in Extension Community Development, often teach and write about the national economy and government policies that can damage it or help it.

Humor aside for a moment, the topic of the deficit and the debt is extremely important. Remember back in 2011 and 2013 when the Congress of the United States seriously threatened to refuse to raise the debt ceiling? Remember the “fiscal cliff” of late 2012? These events caused shock waves to drive through the entire world and almost led to a catastrophe that would have severely damaged the world economy and cost hundreds of millions of people their jobs. And I am not talking about people in the financial sector. I am talking about people in all lines of work – people in communities throughout the United States. You want to talk about community development? Extension does a great job in this effort, but national recessions always rob communities of resources they need in order to thrive, despite the best efforts of elected officials, business people, or outreach educators. That is one of the reasons why I, as a faculty member in Extension Community Development, often teach and write about the national economy and government policies that can damage it or help it.

The difference between the budget deficit and the national debt

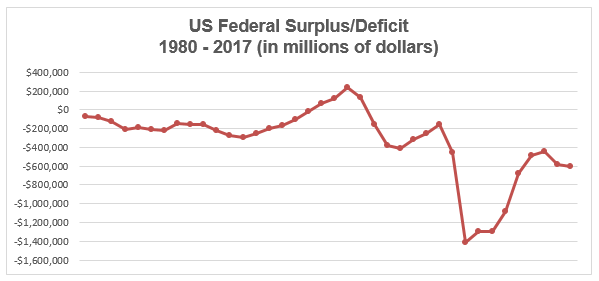

Each year the US government collects taxes from the public and spends money on everything from national defense to education. When the government spends more money than it takes in by way of taxes, it runs an annual deficit. If tax revenues exceed spending, we have a budget surplus. Budget deficits are the norm in the USA. Over the past 50 years, we only have had five years of surpluses, one under President Johnson and four from 1998-2001 under President Clinton. As deficits accumulate from one year to the next, the total amount the government owes is called the national debt. The government finances its debt by selling treasury bonds. We hear a lot of hype about who owns these bonds and what happens if they quit buying them. But the truth is that most treasury bonds are held in one form or another by the American public. Pension funds for example, put an enormous amount of the contributions they collect from workers into these bonds because they are such a safe investment. Commercial banks do the same.

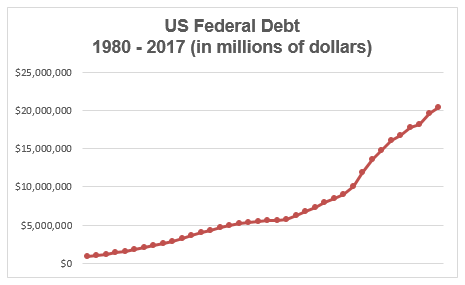

Since the US almost always runs an annual deficit, it is obvious that the national debt increases over time. To many people, when they see these numbers, they become alarmed. The national debt first reached $1 trillion about the time Ronald Reagan took office in 1981. President Reagan created all kinds of useless descriptions about the magnitude of this debt – for example stating how high a stack of 1 trillion dollars would be if you piled them all up. This is not a very constructive way to describe any kind of economic phenomenon, but it does often succeed in scaring or angering voters.

The 2011 Debt Ceiling Crisis

As I explained before, the US government acquires a debt by running annual deficits over time. Those deficits are the result of the policies in taxing and spending (called fiscal policies) passed by the Congress and signed by the President. But the Congress also passes laws that limit the amount of national debt the US can acquire. This limit is called the “debt ceiling.” A debt ceiling may seem strange to you, and it really does not make economic sense, but that is what they do. It does not make sense because the debt the US acquires is just a result of the fiscal policy the Congress itself has set. It would be like a family acquiring debt by financing a house, car, etc., based on a household budget it has developed, but then setting some arbitrary debt number that it cannot exceed. Over the years however, raising the ceiling had just been a formality. After all, the Congress had raised the ceiling an average of about 5 times each under President Reagan, Bush 41, Clinton, and Bush 43. But that would all change under President Obama.

In 2010 the Congress set the debt ceiling at about $14.4 trillion. It soon became clear that the US would hit the ceiling by August 2, 2011. Once the ceiling would be reached, the US government would face the likelihood of default on its debt, and would have to take drastic measures, like refusing to pay bond holders, shutting down entire programs, refraining from paying government obligations like money to defense contractors, laying off government workers, etc. More importantly, it would almost certainly cause a US recession and a worldwide economic crisis like we had in 2008.

The Republican leadership of the Congress informed President Obama that they would only raise the debt ceiling under certain circumstances. Many insisted that the President agree to a dollar for dollar cut in government spending (one dollar cut for each dollar increase in the ceiling). Realizing the urgency of the situation, the President agreed to large budget cuts, but only those that would take place in the distant future. As a result, an agreement was reached and the ceiling was raised to $16.4 trillion, which would put off any further crisis until after the 2012 election. Essentially, the parties agreed to “kick the can down the road.”

Junk Economic Science Meets Junk Politics

One question you might be asking is why would the Republican leaders of Congress risk pushing the economy to the brink of a crisis like this? Well that is a great question. Some people really do become alarmed when they see very large numbers, say in the trillions, especially when they are tied to debt. Unfortunately, very few people and as we shall see, including economists, understand the role that national debt plays in an economy of a country that issues its own currency (see my previous blog “Could America Become like Greece?”).

It turns out that a year before the 2011 ceiling crisis, a pair of very well-known economists (Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff – hereafter R&R) published an article in the American Economic Review that purported to show that countries with high debt levels experience low rates of economic growth.

Now, if this notion were true, it would provide quite a bit of rationale for “deficit hawks” and others who wish to maintain a debt ceiling or impose a balanced budget requirement on the US government. But some enterprising and skeptical economists soon got hold of the data that R&R used. Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin – (hereafter HAP) showed that R&R had omitted a great deal of the data and had coding errors in other parts. These are egregious mistakes, and when HAP corrected them, they showed that the conclusions R&R had made were completely false. R&R acknowledged some of the mistakes fairly quickly, but they denied others, and have since doubled down on the basic claim that high national debt is associated with low growth, even though scholars like HAP have shown that this is simply not the case. Unfortunately, the erroneous view provided by R&R continues to provide cover for politicians who want to maintain the national debt as an issue over which to fight.

The 2013 Debt Ceiling Crisis

At the end of 2012, just after the re-election of President Obama, the US was about to reach the new debt ceiling of $16.4 trillion it had set in 2011, along with a related threat called the “fiscal cliff.” The Congress and the President agreed on a set of continuing resolutions that kept the government funded until October 1, 2013. On this date, the government began a partial shutdown by laying off slightly more than three quarters of a million workers. The Treasury Department warned that even with the layoffs, the government would default by October 17th. On October 16th, the Congress passed a resolution that suspended the debt ceiling. All federal employees went back to work and received full payment for the time they had been laid off. The crisis was over. Seeing the public opinion numbers, Senator Mitch McConnell (R-Ky) vowed that the Congress would not force a ceiling crisis or a government shutdown again. A dreary and completely unnecessary saga in the history of American political economy had finally ended.

Aftermath and Outlook

And the national debt? Well it has risen from $16.7 trillion in October 2013 to $19.8 trillion in July 2017, and is currently rising at $602 billion per year. So, why don’t we hear much about it anymore? I mean, if the debt was a problem at $14 trillion in 2011, and worth a partial government shutdown at $16 trillion in 2013, surely it is a tremendous threat at nearly $20 trillion now – right? It stands to reason, doesn’t it? No, the truth is, it doesn’t, because the national debt was never a problem to begin with. And the alarmists who said it was, whether they were economists who were incompetent or worse, or whether they were politicians who had an axe to grind with a President they wanted to humiliate, dragged the country through years of uncertainty and alarm over nothing.

And the national debt? Well it has risen from $16.7 trillion in October 2013 to $19.8 trillion in July 2017, and is currently rising at $602 billion per year. So, why don’t we hear much about it anymore? I mean, if the debt was a problem at $14 trillion in 2011, and worth a partial government shutdown at $16 trillion in 2013, surely it is a tremendous threat at nearly $20 trillion now – right? It stands to reason, doesn’t it? No, the truth is, it doesn’t, because the national debt was never a problem to begin with. And the alarmists who said it was, whether they were economists who were incompetent or worse, or whether they were politicians who had an axe to grind with a President they wanted to humiliate, dragged the country through years of uncertainty and alarm over nothing.

So you might be wondering – if the government can just run up debt to pay for what it wants, why have taxes? Just borrow the money, right? The answers to those questions lie in the final part of the title to this blog – the part about the value of money. Taxes are used in part to pay for government expenses – that is true. But taxes are what provide the foundation for the value of money. That’s right, the reason that those paper bills and coins you carry around, or those digits on your computer screen when you check your bank account balance or make an online purchase have value at all is because of taxes, as we will see in detail in my next blog.

References

Herndon, T., Ash, M., & Pollin, R. (2014). Does high public debt consistently stifle economic growth? A critique of Reinhart and Rogoff. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 38(2), 257-279.

Reinhart, C. & Rogoff, K. 2010. Growth in a time of debt, American Economic Review, 100 (2), 573-578.

Tom Blaine is an Associate Professor, OSU Extension.

So the ability

To raise taxes ensures we have a healthy

Currency or

Value in that currency and therefore a healthy economy despite our debt level .. And a healthy economy produces more tax revenue and more investors who want to buy your currency .. So best to create and maintain a healthy

Workforce ?? Kieran J aka Special K