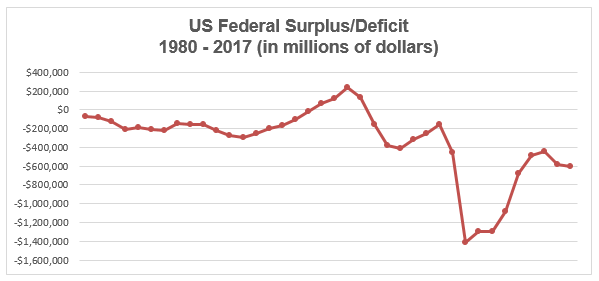

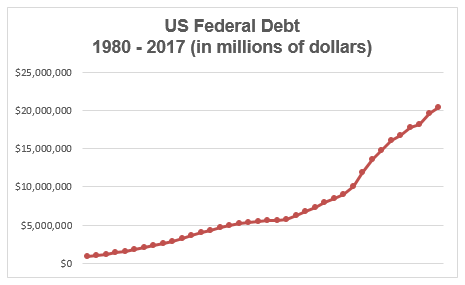

In my last blog post, which you can read here, I explained the difference between the federal budget deficit and the national debt and showed how they are related to each other. I severely criticized the Republican party for the way its leaders used the issue of the national debt to try to humiliate President Obama throughout his presidency. The Republicans claimed that a $14 trillion dollar debt and then a $16 trillion dollar debt etc. were grave threats to the national economy. I showed that the national debt at these levels was in fact not a threat at all, and that the Republicans and some rogue economists either knew or should have known that this was the case.

Update: Now that the Republicans control both houses of Congress and the White House, they recently passed “tax reform” that will cause the debt to soar to well above $21 trillion. This of course proves that Republican political leaders have simply been opportunists and hypocrites all along, confirming the charges I was making in the previous blog piece. For the purposes of my point, the timing could not have been more ideal.

I ended the previous blog piece by asking the questions: If the national debt is not the problem that “deficit hawks” claim it is, then why should the federal government levy taxes at all? Why not just borrow the money?

How the Modern Monetary System Works

Before I give you the answers to these questions, let me remind you that modern economies use as money what is called fiat currency. This means that the currency is not backed by any physical commodity like gold or silver, it is only backed by government fiat – Latin for “let it be done.” The American dollar, the Chinese yuan, the euro, the yen, the British pound, the Russian ruble are all fiat currencies.

Now we are ready to answer the questions about taxes and debt. The answer to these questions is that taxation is what gives a currency its value. If you ever thought much about it, you probably have considered the horrors of living in a barter economy – where you have to find somebody who has what you want and also happens to want what you have and then strike a deal. So money, of course, ends this problem. But money (read: currency) such as the US dollar must have a foundation in taxation in order to have intrinsic value so that people will accept it in lieu of a good or a service (barter).

The best explanation I have ever heard for this reality comes from Warren Mosler. He was giving a seminar at the time and the story runs something like this. Suppose someone is in a room giving a seminar and holds up his business card and asks who wants one. Many in attendance will take a pass and turn down the offer. After all, you can probably get the presenter’s contact information from the Internet, so the card has little to no value. Now suppose the presenter says, “There is an armed man outside the door who is going to escort you to jail if you attempt to leave the room without handing him one of my cards.” Suddenly everybody wants a card! They simply must have it. Now the presenter says that you must do something like tidy up the room a bit in order to acquire a card. People went from being indifferent about having a card, to wanting one, to even being willing to work to obtain one. That’s quite a turnaround. And it happened because they were coerced by the threat of losing their freedom if they did not hand over the card upon leaving the room.

This is precisely why fiat money has value. As Benjamin Franklin once said, “Nothing is certain except death and taxes.” One way or another, you are going to have to pay your taxes, and since the issuer of a currency (in this case the United States government) only accepts payment for taxes in dollars, you must obtain dollars, just as the folks in the seminar must obtain the business cards. And since everybody ultimately needs dollars to pay their taxes, there is simply no substitute for them. You can talk about gold, silver or even bitcoin all you want, but in the final analysis, you must obtain money in the form of the currency with which you pay your taxes.

Pushing the analogy a little further, imagine what might happen if there are 50 people in the room but the presenter only brought 40 cards. Everyone may be willing to work, but there are simply not enough cards to go around. So some people are just not going to make it out of the room. These people are stuck. In economic terms they are unemployed. No matter how genuine their intentions, they are in dire straits – not because of anything they did wrong, but because of something the presenter did wrong – not bringing enough cards. In other words, the root cause of unemployment is that the government has not produced enough currency. It needs to issue and spend more in order to make it possible for everyone to get out of the room (read: to be employed).

Suppose the presenter brought 60 cards. Some people might be willing to do some extra work to obtain extra cards and they may “employ” someone in the room to do a task for them to in order to obtain a card that they have earned. So now cards are circulating among attendees, just as money circulates between consumers and businesses in the economy. Some attendees may work to gain extra cards so that they will have them when they come to a future seminar. This is the equivalent of economic growth, and is of course desirable. But at some point, if the presenter has brought and hands out an overabundance of cards, attendees who want others to do tasks for them are going to have to offer more cards per chore. The value of the cards will eventually decline in this circumstance. This is inflation, and it comes about when the government issues too much currency for the amount of economic activity people need or desire.

So there you have it. Money has value, not because it is shiny or aesthetically pleasing. It has value because government taxation gives it the traction it needs to have value. And you and I reap the benefits of a stable currency within a stable economy. The challenge is to manage the supply of currency in order to prevent unemployment and inflation. Artificial restrictions on the federal government’s ability to manage the money supply (like a gold standard, fixed exchange rates, a debt ceiling or a balanced budget amendment) are counterproductive and must be avoided. It took decades of the recurrence of devastating depressions, culminating in the catastrophe of the Great Depression of the 1930s before countries such as the USA learned that using a currency backed by metals such as gold was a recipe for continued needless hardship – hence the move toward fiat currencies.

Two Kinds of Entities in the World: (1) The One Who Issues a Currency and (2) Everybody Else

With its own fiat currency, concern about the federal government “running out of money” because of debt is unfounded because the federal government alone creates currency and therefore can never run out. Note that this is NOT true however for state and local governments because they cannot create currency like the federal government can. If they get into debt, it can mean very serious trouble. That is why many states and municipalities have balanced budget requirements.

The same thing is true for a country that does not issue its own currency, like those in the eurozone, such as Greece, which has been facing a national debt crisis for nearly a decade now. Read my blog on a comparison between the debts of a country with its own currency like the USA and one that does not have its own currency like Greece here.

So when the economy of a country that issues its own currency slows down, goes into recession, and unemployment rises, the government has a duty to respond by producing and spending more currency. This will cause the deficit and the debt to rise. Sayings such as, “businesses and families are tightening their belts, so the federal government must tighten its belt too” are erroneous because as we have seen, the entities are not comparable. If the government fails to increase spending in such circumstances, more people will become unemployed and the recession will get worse, just as more people will be stuck in the room if the presenter failed to bring enough cards.

On the other hand, tax cuts when the economy is strong, as it is now, make no sense at all and will increase the debt for no reason other than to transfer wealth from the middle and working classes to the wealthiest, which has really been the Republican economic agenda all along.

A Government That Issues its Own Currency Does Not Need Tax Revenue to Fund its Operations, But it Does Need to Levy Taxes

Another point of the business card analogy is that the federal government does not tax anyone because it needs the money. When you think about it, it would be absurd to imagine that the US government needs dollars from anyone, since it literally can create all the dollars it wants out of thin air. In fact, every dollar you have in your possession or ever have had was literally created by the federal government and then spent. Otherwise you simply would not have it. On the other hand, when the federal government obtains the currency back, it just destroys it – literally, and then creates new currency in its place. It doesn’t need your money any more than the person presenting the seminar needs the business cards collected by the man at the door.

Moreover, notice that taxes do not come first – federal government spending comes first. If the presenter in the seminar analogy does not bring cards and spend them into circulation, then there would be no cards available for the man at the door to collect from the attendees. Similarly, if the government does not spend first, there would be no dollars in circulation among businesses and consumers to collect in taxes. Think about that the next time you hear a person complain about “tax and spend.” They have it backwards – it is spend and tax – and without that, we simply could not have a modern economy at all.

I encourage you to watch the video where Warren Mosler gives the analogy to business cards and money in a debate he had with a “libertarian” economist. Including what I have discussed in the blog, Warren describes the differences between private and sovereign government debt, the benefits of a currency not backed by gold or other metals, and why US government spending, which is often vilified by right wing politicians and the media, is imperative to maintaining a sound economy.

Warren Mosler and Tom Blaine, 2015, Saint Croix

I had the opportunity to meet Warren personally in 2015 near his home in Saint Croix. Here is a photo of the two of us talking economics on an 80 degree January day. Not only is Warren a formidable thinker, he is a gracious host.

So of the two questions I posed near the beginning of the blog, we definitely have an answer to the first: why the federal government must levy taxes. But now a question may have entered your mind that flips the second question (about borrowing) on its head: Why does the US government have to borrow money at all? In other words, if the government can issue dollars out of thin air, why does it borrow money in the form of dollars (from, say China) to finance the debt? We know it really does not need to levy taxes to obtain dollars, so why does it need to borrow to obtain them?

The US undertakes borrowing primarily by selling bonds to banks, pension funds, other governments, etc. with a promise to repay the money with interest by a certain date. As we have seen, the value of the outstanding US federal debt is now approaching $21 trillion. But if we go back to our analogy from Warren Mosler, that would be like the seminar presenter offering bonds to anyone who would lend him his own business cards with the promise that he would pay them back with interest in the future. Why would he do that? It doesn’t seem to make sense, does it? Well it may not make sense, but it is the way the system works, and I will explain why in my next blog.

Tom Blaine is an Associate Professor, OSU Extension.

Humor aside for a moment, the topic of the deficit and the debt is extremely important. Remember back in 2011 and 2013 when the Congress of the United States seriously threatened to refuse to raise the debt ceiling? Remember the “fiscal cliff” of late 2012? These events caused shock waves to drive through the entire world and almost led to a catastrophe that would have severely damaged the world economy and cost hundreds of millions of people their jobs. And I am not talking about people in the financial sector. I am talking about people in all lines of work – people in communities throughout the United States. You want to talk about community development? Extension does a great job in this effort, but national recessions always rob communities of resources they need in order to thrive, despite the best efforts of elected officials, business people, or outreach educators. That is one of the reasons why I, as a faculty member in Extension Community Development, often teach and write about the national economy and government policies that can damage it or help it.

Humor aside for a moment, the topic of the deficit and the debt is extremely important. Remember back in 2011 and 2013 when the Congress of the United States seriously threatened to refuse to raise the debt ceiling? Remember the “fiscal cliff” of late 2012? These events caused shock waves to drive through the entire world and almost led to a catastrophe that would have severely damaged the world economy and cost hundreds of millions of people their jobs. And I am not talking about people in the financial sector. I am talking about people in all lines of work – people in communities throughout the United States. You want to talk about community development? Extension does a great job in this effort, but national recessions always rob communities of resources they need in order to thrive, despite the best efforts of elected officials, business people, or outreach educators. That is one of the reasons why I, as a faculty member in Extension Community Development, often teach and write about the national economy and government policies that can damage it or help it.

And the national debt? Well it has risen from $16.7 trillion in October 2013 to $19.8 trillion in July 2017, and is currently rising at $602 billion per year. So, why don’t we hear much about it anymore? I mean, if the debt was a problem at $14 trillion in 2011, and worth a partial government shutdown at $16 trillion in 2013, surely it is a tremendous threat at nearly $20 trillion now – right? It stands to reason, doesn’t it? No, the truth is, it doesn’t, because the national debt was never a problem to begin with. And the alarmists who said it was, whether they were economists who were incompetent or worse, or whether they were politicians who had an axe to grind with a President they wanted to humiliate, dragged the country through years of uncertainty and alarm over nothing.

And the national debt? Well it has risen from $16.7 trillion in October 2013 to $19.8 trillion in July 2017, and is currently rising at $602 billion per year. So, why don’t we hear much about it anymore? I mean, if the debt was a problem at $14 trillion in 2011, and worth a partial government shutdown at $16 trillion in 2013, surely it is a tremendous threat at nearly $20 trillion now – right? It stands to reason, doesn’t it? No, the truth is, it doesn’t, because the national debt was never a problem to begin with. And the alarmists who said it was, whether they were economists who were incompetent or worse, or whether they were politicians who had an axe to grind with a President they wanted to humiliate, dragged the country through years of uncertainty and alarm over nothing.