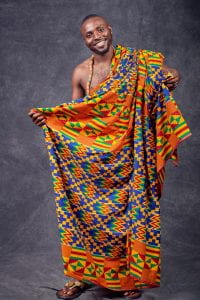

Ishmael Konney is an OSU alumnus who earned his M.A degree in International Studies from Ohio University and his MFA degree in Dance from Ohio State University. Shurouq Ibrahim, CSR’s Graduate Research Associate, interviewed Ishmael to ask what the Iles Award meant to him!

Shurouq: Could you tell me about your research as a graduate student/alumnus of OSU?

Ishmael: Thank you for this opportunity. My larger research interest focuses on the promotion of the Ghanaian cultural identity and every project I embark on is under the auspices of this research. My immediate research explores the intersectionality between Ghanaian cultural practices and contemporary dance.Looking at ways that I can share my Ghanaian values in the work I make on and off stage. Currently the cultural practice I work with is traditional Ghanaian storytelling.  Ghanaian storytelling encompasses music, dance, theatre, other visual arts and dissolves any division between the performers and the audience, creating a participatory environment in which every person involved is important. With my training in music, theatre and dance, storytelling becomes a conglomerate and a medium for me to share my artistic expertise while fostering a communal experience for the audience and performers. So, you can think of my research as a pyramid scheme, where the main idea at the top births multiple interests but every new interest is tethered to the main idea at the top.

Ghanaian storytelling encompasses music, dance, theatre, other visual arts and dissolves any division between the performers and the audience, creating a participatory environment in which every person involved is important. With my training in music, theatre and dance, storytelling becomes a conglomerate and a medium for me to share my artistic expertise while fostering a communal experience for the audience and performers. So, you can think of my research as a pyramid scheme, where the main idea at the top births multiple interests but every new interest is tethered to the main idea at the top.

Shurouq: How does your research intersect with the study of myth and religion, if at all? Why do you think the study of religion is important?

Ishmael: The research that got me the [Iles] award “W)gb3j3k3” was investigating the migration of the Ga people. History has it that the Ga people migrated from Israel to their present location. Most of the Ghanaian stories are embedded in our oral traditions and these stories are passed on from generation to generation through folktales, legends, and myths. My culture is preserved through myths and folktales so my history cannot be accessed without talking about and honoring these oral traditions. According to Paschal Younge in his book I Am a Ghanaian Cultural Ambassador: A Manual for Traditional Drumming and Dance Groups of Ghana, “there were no tangible or reliable documentary sources on Ga history before the 1600’s. Most of the history can be found in folktales, songs, legends, myths, poems, and other traditional oral sources” (2016, 135). The study of religion aids in understanding the people that are being studied, their beliefs and their way of life. This becomes a bedrock to understand how these histories exist and are embedded in the culture of the people. It is essential to examine the religion of a group of people while studying their history.

Shurouq: How did you hear about the Iles Award offered through the Center for the Study of Religion?

Ishmael: Faculty in the dance department at OSU always share funding resources to the grad students. Similarly, an email was shared about this funding opportunity, and I did not hesitate to apply because my research project was a perfect fit.

Shurouq: And how did the Iles Award contribute to the advancement of your research?

Ishmael: Firstly, it was and is still expensive to travel to Ghana from the US and this award defrayed majority of the travel cost. I was able to have conversations around the traditions of the La people and that developed into a documentary which was not part of my initial plans. The initial goal was to record the conversation about the migration so I could generate movements and build the concept for my final piece. The conversations were educative, and I wanted to share the information with other people and the world so I scheduled with the religious leader to have another interview that developed into a documentary about the history of the La people.

Shurouq: Where are you currently? And what are your current projects?

Ishmael: I am currently an Assistant Teaching Professor of Dance in the Department of Theatre and Dance at Ball State University, located in Muncie, Indiana. I also serve as a dance faculty at Kentucky Governors School for the Arts Summer program. My recent project was a collaborative piece choreographed by myself and Jenn Meckley (dance faculty at Ball State) titled “Fusion”. It was a piece that celebrated community through various cultures, identities, movement, and music, and emphasized the dynamic interweaving of traditional West African forms, American house dance, Afro-house dance, dancehall, Afrobeats, and Hip-hop.

Shurouq Ibrahim: Thank you!

To watch Ishmael’s documentary, click here.

At different times, throughout history, this myth becomes a source for people to perform a vernacular religious theatre that is called Ta’ziyeh, and I have that in the title [of my dissertation]. As I said, Ta’ziyeh literally means mourning. So, people reenact that story via Ta’ziyeh. Throughout history, sometimes [Ta’ziyeh] was complicated; it was forbidden, [but] sometimes it was a national symbol of the country [Iran] — we have a Karbala vernacular folkloristic theatre…

At different times, throughout history, this myth becomes a source for people to perform a vernacular religious theatre that is called Ta’ziyeh, and I have that in the title [of my dissertation]. As I said, Ta’ziyeh literally means mourning. So, people reenact that story via Ta’ziyeh. Throughout history, sometimes [Ta’ziyeh] was complicated; it was forbidden, [but] sometimes it was a national symbol of the country [Iran] — we have a Karbala vernacular folkloristic theatre…