Congratulations to CSR’s latest Iles Award winner, Evan DeCarlo!

Evan is a doctoral fellow in the interdisciplinary Folklore Program of The Ohio State University’s English Department. His research interests cover the legendry genre, digital narrative, and the intersection between folklore and Web 2.0 era vernacular spaces and modes. Shurouq Ibrahim, CSR’S Graduate Research Associate, sat down with Evan to see what the CSR’s Iles Award means for his research!

Shurouq: Can you tell me about your research as a graduate student at OSU?

Evan: I am a Ph.D student of the English department but, also, as a person with their focus in folklore, half my research is also involved in Comparative Studies which is how the folklore program works. My research, as a folklorist, focuses primarily on the legend genre, which is an interesting term. Legend. It has a particular meaning to folklorists and one that I’ll talk about a little bit; it has a kind of all-over-the-place meaning. But it also has a more exoteric definition in the broader — we can say, the Anglophone world — particularly North America. And I have looked at legend from a lot of different angles for a lot of my research career as a grad student…But for my dissertation, I wanted to take a look at what I have decided to call “hoax-lore”— manufactured legend — legend we wouldn’t, by a conventional, sort of traditional, definition of legend…recognize as necessarily belonging in that genre because of their authorial provenance. The full title of the dissertation, which is kind of a mouthful, is “Hoax-Lore: The Aestheticization of Truth through Fabricated Legend,” which is a lot, but [it] gives you the components of what’s going on…The big two things that stick in addition to legends being localized are these two other factors that really oscillate a lot: truth and belief in the way that — throughout the twentieth century — trying to define legend has a lot to do with what different scholars have to say about truth and belief…Going into mid-century folkloristics and beyond, we have this idea that when we use the term “legend” out and about and in our daily lives, I think what we tend to mean is: it’s fiction, that’s just a legend; it’s just made up, it’s not real, it’s not true. Folklorists have been using a — not identical — but in many ways similar definition for legend especially as a way to delineate or delimit, or even demarcate, the genre from its sister genres of something like tale, or fairy tale, and then myth, on the other hand. The way legend has been variously defined then floats around these two factors: truth and belief.

Shurouq: Right. And this brings me to my second question: How does your research intersect at all with the study of religion?

Evan: Sure. Certainly, nominally, I am not studying religion at all, but what I am definitely studying is belief, which certainly has quite a lot to do with religion. There’s been a lot of talk in folkloristics about the rhetoric of believability, and I think to some extent my research really embraces this. It says: What are we learning about what it takes to believe something? Another way of phrasing that question would be: What does it take to understand something as true, as potentially believed, or as truly believed? And to that end, I think what looking at hoax-lore and the way it moves (and legend in general) has taught me is that truth has a lot less to do…with a platonic sense of truth than it might with…believability…This really interesting idea of truth as collectively and culturally instantiated via repetition and consensus, and then the sort of simulation of that process is very interesting to me at least in the way it’s been expressed in…hoax-legends. Now I don’t know how much you might be able to move this into the world of the study of religion, but I certainly think there is application especially just via the ritualization of a lot of these factors — the traditionality of them as well.

Shurouq: Nice! And what did the Iles Award mean for your research? How did it advance your research in any way?

Evan: Well, I think building on what I just said, that was the idea that my research could have some cachet, some legs, in a field nominally other than folkloristics was really inspiring to me. A group of people who were working for the Center for the Study of Religion and participating in all these other different disciplines could still look at it and say, “I think there’s something here worth talking about” — outside the primary context of folkloristics — was definitely [important]. Other than just the monetary aid of the award…maybe there is some utility to what I am looking at here….That’s a really nice way for a graduate student to be inspired to keep working. Maybe what I’ve considered as a very esoteric little niche [interest] isn’t so squirreled away after all. And then over the summer, I took my project to an interdisciplinary conference in Serbia, of all places, which was primarily an international relations conference and got some political scientists to comment on it. And it turns out there may be applications there too. When you take a concept like the “fake,” the “hoax”…and you give yourself permission to not think about it that way…you get a lot of mileage out of it. And I think that the Iles Award, for me, was sort of like a permission to start examining this from other perspectives. That there was a hospitality to this kind of thinking in disciplines other than my own sub-sub-sub field, which was really encouraging. And then, of course, just being able to have some money as a graduate student has been extremely helpful.

Shurouq: Wonderful! Thank you for this, Evan!

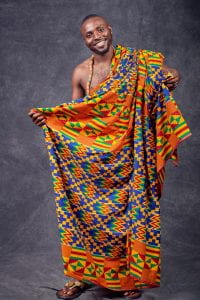

Ghanaian storytelling encompasses music, dance, theatre, other visual arts and dissolves any division between the performers and the audience, creating a participatory environment in which every person involved is important. With my training in music, theatre and dance, storytelling becomes a conglomerate and a medium for me to share my artistic expertise while fostering a communal experience for the audience and performers. So, you can think of my research as a pyramid scheme, where the main idea at the top births multiple interests but every new interest is tethered to the main idea at the top.

Ghanaian storytelling encompasses music, dance, theatre, other visual arts and dissolves any division between the performers and the audience, creating a participatory environment in which every person involved is important. With my training in music, theatre and dance, storytelling becomes a conglomerate and a medium for me to share my artistic expertise while fostering a communal experience for the audience and performers. So, you can think of my research as a pyramid scheme, where the main idea at the top births multiple interests but every new interest is tethered to the main idea at the top.

At different times, throughout history, this myth becomes a source for people to perform a vernacular religious theatre that is called Ta’ziyeh, and I have that in the title [of my dissertation]. As I said, Ta’ziyeh literally means mourning. So, people reenact that story via Ta’ziyeh. Throughout history, sometimes [Ta’ziyeh] was complicated; it was forbidden, [but] sometimes it was a national symbol of the country [Iran] — we have a Karbala vernacular folkloristic theatre…

At different times, throughout history, this myth becomes a source for people to perform a vernacular religious theatre that is called Ta’ziyeh, and I have that in the title [of my dissertation]. As I said, Ta’ziyeh literally means mourning. So, people reenact that story via Ta’ziyeh. Throughout history, sometimes [Ta’ziyeh] was complicated; it was forbidden, [but] sometimes it was a national symbol of the country [Iran] — we have a Karbala vernacular folkloristic theatre…