Congratulations to CSR’s latest Iles Award winner, Matt Maynard!

Matt Maynard is a PhD candidate in Classics. He is writing a dissertation on the god Pan and ancient Greek ideas about wilderness. Shurouq Ibrahim, CSR’S Graduate Research Associate, sat down with Matt to see what the CSR’s Iles Award means for his research!

Shurouq: Could you tell us what you’re working on?

Matt Maynard

Matt: Sure. I’m a Ph.D student in the Department of Classics. I’m currently in the end stages of my dissertation work. I am planning to graduate this summer. About my work: I began my graduate stiduies with a general focus on the religious thought and practices of the ancient Greeks and then I came to focus on the god Pan in particular, who is a god who held particular significance to shepherds, and who was thought to dwell in the wild places of the world. At the same time, I’ve been digging into the newish field of eco-criticism and finding that some of the ideas that have come out of that field have potential to change the way that we read landscape and environment not only in literature but in other forms of cultural expression like myth and religious beliefs, too. I have been bringing those ideas into my study of the god Pan to just think through Ancient Greek ideas about the natural world.

Shurouq: Nice, that’s fascinating! So you already touched on this, but how would you expand on this to say how your research intersects more with the study of religion?

I look at a number of texts and myths concerning Pan for my dissertation, but I focus primarily on a poem that’s known as the Homeric hymn to Pan, which was composed — we don’t know exactly — but some time in the 6th or 5th century B.C. As a hymn, the poem has a clear religious orientation, so a big part of what I am doing is commenting on the relationship between religion and the environment, and I look at other Greek hymns too and suggest that these occasions for religious expression were also felt by the Greeks to be apt occasions for reflections on human ecology, not just in terms of our place in the cosmos, but also more narrowly our place and function on the earth with regard to other life forms and materials that we share this place with.

Shurouq: Thank you. And my last question, how is the Iles Award meaningful for your research? How will you use it to expand on your work?

It’s a great encouragement first of all for me to keep working with these ideas, and it’s a real validation that my project has some legs. I would say it’s especially gratifying to see that people from outside of my home department saw some worth and took an interest in what I have been working on. Eco-criticism is by its nature an interdiscplinary field that seeks out and really needs conversation between people with different specializations. The financial support is of course very welcome, too. And getting to the end of a Ph.D I’m finding is a very hectic time, so the award has also made it possible to take a little bit of time and develop this project, hopefully, into something that’s publishable.

Shurouq: Wonderful! Thank you, Matt!

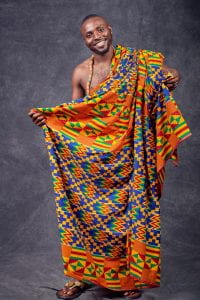

Ghanaian storytelling encompasses music, dance, theatre, other visual arts and dissolves any division between the performers and the audience, creating a participatory environment in which every person involved is important. With my training in music, theatre and dance, storytelling becomes a conglomerate and a medium for me to share my artistic expertise while fostering a communal experience for the audience and performers. So, you can think of my research as a pyramid scheme, where the main idea at the top births multiple interests but every new interest is tethered to the main idea at the top.

Ghanaian storytelling encompasses music, dance, theatre, other visual arts and dissolves any division between the performers and the audience, creating a participatory environment in which every person involved is important. With my training in music, theatre and dance, storytelling becomes a conglomerate and a medium for me to share my artistic expertise while fostering a communal experience for the audience and performers. So, you can think of my research as a pyramid scheme, where the main idea at the top births multiple interests but every new interest is tethered to the main idea at the top.

At different times, throughout history, this myth becomes a source for people to perform a vernacular religious theatre that is called Ta’ziyeh, and I have that in the title [of my dissertation]. As I said, Ta’ziyeh literally means mourning. So, people reenact that story via Ta’ziyeh. Throughout history, sometimes [Ta’ziyeh] was complicated; it was forbidden, [but] sometimes it was a national symbol of the country [Iran] — we have a Karbala vernacular folkloristic theatre…

At different times, throughout history, this myth becomes a source for people to perform a vernacular religious theatre that is called Ta’ziyeh, and I have that in the title [of my dissertation]. As I said, Ta’ziyeh literally means mourning. So, people reenact that story via Ta’ziyeh. Throughout history, sometimes [Ta’ziyeh] was complicated; it was forbidden, [but] sometimes it was a national symbol of the country [Iran] — we have a Karbala vernacular folkloristic theatre…