A few weeks ago, we had the pleasure to host Dr. Solimar Otero, professor of folklore at Indiana University, at OSU as she presented on some of her most recent work, including her 2020 book Archives of Conjure: Stories of the Dead in Afrolatinx Cultures. We also got the chance to sit down with her and talk in more detail about her work in the book—her approach, motivations, biggest take-aways, and future plans. Take a look at the video and interview below to get a taste of how Dr. Otero’s research opens up new possibilities to think about how the material artifacts of the archive actively forge meaningful and transformational bonds with our ancestors. FOLLOW THIS LINK to learn more and purchase her book!

Q & A with Dr. Otero:

How did this project start?

I began the fieldwork and archival research for Archives of Conjure at the Harvard Divinity School’s Women’s Studies in Religion Program (WSRP) as a Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of African Diaspora Religions in 2009–2010. The support from the WSRP allowed me to travel to Cuba to set up the initial framework for the book, which at that point was primarily ethnographic interviews and participant observation in rituals conducted with women and LGBTQ practitioners of Afro-Cuban religions. My move to incorporate the archives of Ruth Landes and Lydia Cabrera came later with additional support from The Reed Foundation. With these elements in place, I felt I could creatively incorporate literary criticism of Mayra Santos-Febres’ and Lorna Goodison’s works as a way to bring together interdisciplinary explorations of gender, sexuality, and spirituality in Afro-Caribbean and Afrolatina religiosity.

How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

The relationships I established in Cuba with the religious community started with my dissertation research that eventually led to my first monograph, Afro-Cuban Diasporas in the Atlantic World (University of Rochester Press, 2010). The fieldwork and oral histories for this book took place primarily in Lagos, Nigeria. However, the connections and circulation of religious practices, particularly creolized religious practices, between Cuba and Nigeria made a deep impression on me. Doing the work of reconstructing the lives of Afro-Cuban repatriate Yoruba with their descendants planted the seeds of doing the of work vivifying ancestors through research. I wanted to focus more deliberately on gender, sexuality, and race in Archives of Conjure. Thus, I incorporated queer theory, transnational feminist thought, as well as the important theoretical interventions and practices of the communities I worked with in Cuba into the project. The result is a book that reflects a range of interests, approaches, and geographies that is tied together by the idea of tracing ancestors’ intentions, movements, and interventions in the words and material culture they leave behind.

Why was it important for you to write this book?

I wanted to highlight the Afrolatinx communities, past and present, that were doing creative work in archiving their rituals through what I call residual transcriptions. These transcriptions can take on many forms, paper, beading, dolls, altars, etc. It seemed significant that these practices and objects could be shared transnationally and across linguistic differences. I believe these forms of interacting with memory, the world, and each other is an important way to grapple with the trauma of the violence of colonialism and slavery.

Can you describe your methodology/methodologies?

I am an interdisciplinary folklorist who engages with fieldwork, archival practices, and critical methodologies. My work involves thinking through cultural and artistic practices through multiple lenses guided by Afrolatinx religious communities’ ways of being in the world. I am particularly excited by practitioners’ own methods for documenting, reinventing, and activating their history. The theoretical perspectives of Édouard Glissant and José Esteban Muñoz also provided much inspiration for navigating issues of creolization and queer identity in the text.

What key questions do you hope this book will raise for readers?

I hope readers will take seriously the ways that everyday people practicing Afrolatinx religions work through the historical legacies of colonialism and slavery through spiritual inventions that are complex, open, and oriented towards healing. This means looking at rituals and archives in ways that make us question the authority and grand narratives that usually guide ethnography and historiography.

Where did this project lead you? What are you working on next?

Archives of Conjure made me pay attention to the relationship between material culture and storytelling in a new way. I am working on a co-edited volume, with folklorist Anthony Bak Buccitelli, on performance and folklore, Emerging Perspectives in the Study of Folklore and Performance. The book has essays written by folklorists, theatre scholars, and communication studies. My chapter in the volume focuses on how performances that call on the ancestors, like songs and the spoken word poetry, think through the materiality of the spirit through bodily imagery. These metaphors mark the mutable and pervasive nature of Black performance and ritual in a way that fights institutional objectification, violence, and eradication.

* * *

Video Transcript: My book Archives of Conjure: Stories of the Dead in Afrolatinx Cultures, deals with spirit mediums in Afro-Cuban religion, archival research from Brazilian Candomblé culture from the late 1930s, as well as Afro-Puerto Rican literature that deals with Orisha traditions and trans and LGBTQ communities. So, the book is actually really trying to get at the ways that ritual practice, archival artifacts and materials, as well as literature all come together, in Afro-Caribbean and Afrolatinx understandings of what ancestors do and their presence in our world. So, it’s an interdisciplinary book. But it’s a book that’s really based on how artists, scholars, and practitioners have ritual practices that intersect and create this—and it’s called ‘Archives of Conjure’—that create these ways of knowing that can be vivified or conjured in ways that allow us to think through histories that may not be found in the archive, that may not be found in traditional ethnography, but can be elaborated upon if we look at these folkloristic or vernacular ways of how people understand themselves, their history, and their communities.

It’s very rhizomatic. So, the cover of the book has these beads, right? Like these, this is an idé, but the beads that are on the cover are mazos. It’s actually very similar. So, when you see somebody wearing one of these, that usually means they are a priest or priestess. And it actually relates to a story, to a narrative and a particular road of the gods. Every Orisha has an avatar, and those avatars have colors and numbers and symbols associated with them. I’m a daughter of Oshun, so when people see this, they know that my road is Ibu Kole. Because the beads and the colors, have a specific rendering and numbering. And these relate to specific verses and stories that are all bunched up in these many different strands. So, the book, I tried to write it as if it was one of these strands, and they come together in these, we call this a moño, like a knot. And everything comes together, and they’ve come apart and together. So that’s the kind of rhizomatic, diasporic structure of how people can pass on these histories through difference in language, right, because you have similar beading, same beading happening in Brazil, Cuba, Nigeria, and other spaces, and coded because of the ways that black religion was demonized during the colonial period in particular, is still demonized because of class and racism, in many different iterations in different places. So, this coding is something that can be read, but it also is a way of keeping history that’s not found in an archive or an ethnography or necessarily in historiography. So, this is a vernacular way of reading who somebody is, and it brings up all those other elements.

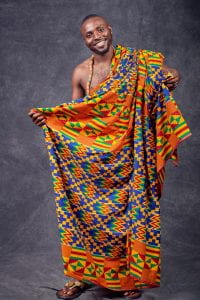

Ghanaian storytelling encompasses music, dance, theatre, other visual arts and dissolves any division between the performers and the audience, creating a participatory environment in which every person involved is important. With my training in music, theatre and dance, storytelling becomes a conglomerate and a medium for me to share my artistic expertise while fostering a communal experience for the audience and performers. So, you can think of my research as a pyramid scheme, where the main idea at the top births multiple interests but every new interest is tethered to the main idea at the top.

Ghanaian storytelling encompasses music, dance, theatre, other visual arts and dissolves any division between the performers and the audience, creating a participatory environment in which every person involved is important. With my training in music, theatre and dance, storytelling becomes a conglomerate and a medium for me to share my artistic expertise while fostering a communal experience for the audience and performers. So, you can think of my research as a pyramid scheme, where the main idea at the top births multiple interests but every new interest is tethered to the main idea at the top.

At different times, throughout history, this myth becomes a source for people to perform a vernacular religious theatre that is called Ta’ziyeh, and I have that in the title [of my dissertation]. As I said, Ta’ziyeh literally means mourning. So, people reenact that story via Ta’ziyeh. Throughout history, sometimes [Ta’ziyeh] was complicated; it was forbidden, [but] sometimes it was a national symbol of the country [Iran] — we have a Karbala vernacular folkloristic theatre…

At different times, throughout history, this myth becomes a source for people to perform a vernacular religious theatre that is called Ta’ziyeh, and I have that in the title [of my dissertation]. As I said, Ta’ziyeh literally means mourning. So, people reenact that story via Ta’ziyeh. Throughout history, sometimes [Ta’ziyeh] was complicated; it was forbidden, [but] sometimes it was a national symbol of the country [Iran] — we have a Karbala vernacular folkloristic theatre…