The words “text” and “textile” share a common root in the Latin word texere, which means “to weave.” The art of weaving in the Andes is considered to be divinely passed down from the mamachas (little mothers or patron saints).

Ethnographic information by Devin Grammon

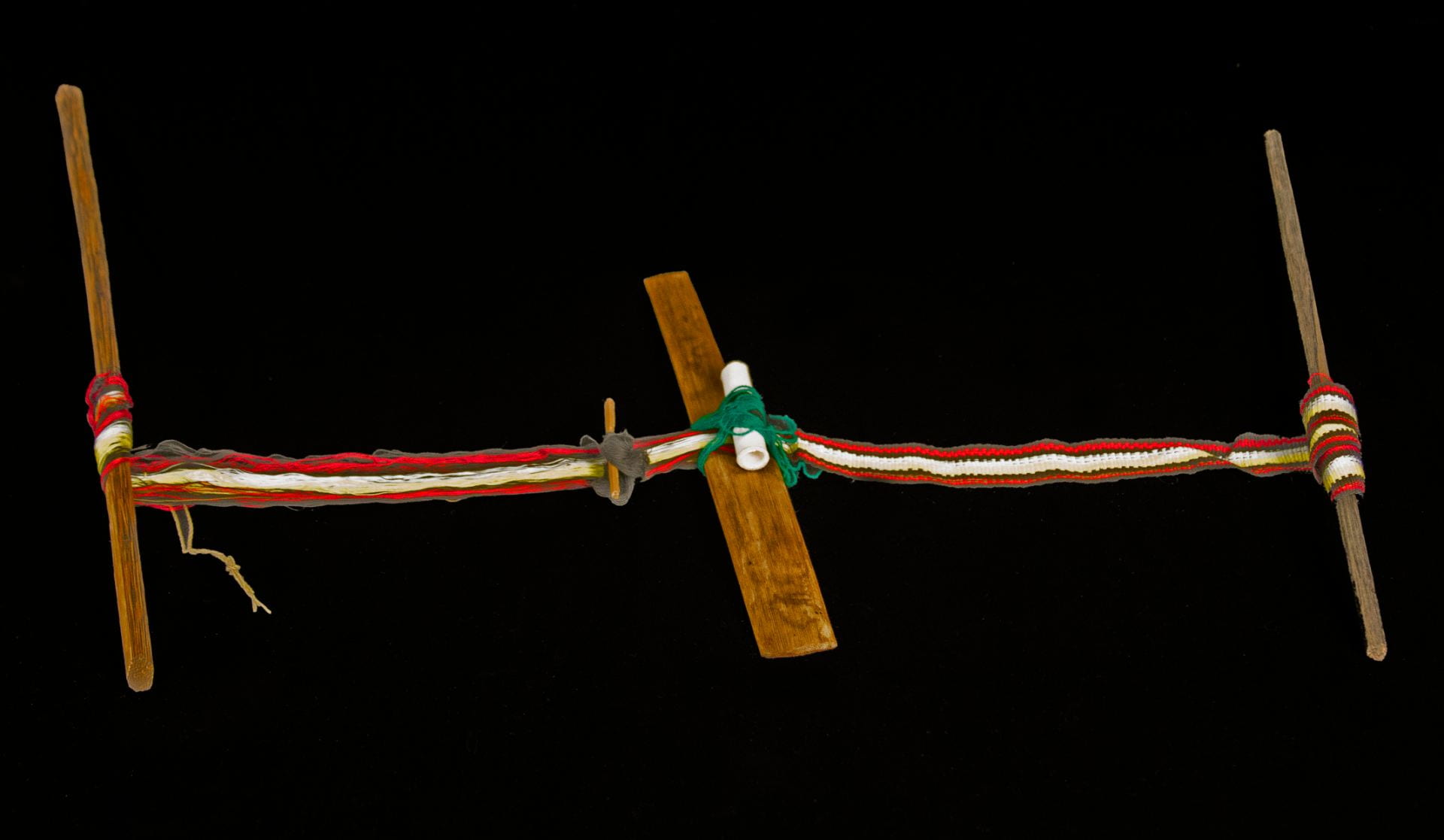

This belt, known in the local Quechua as chumpi or Spanish as faja, was made by local weaver Doña Julia and acquired in Cuzco, Peru. Doña Julia is originally from the community of Chinchero and weaves daily on the steps of Qanchipata in the San Blas neighborhood of Cuzco.

The belt’s patterns consist of repeating diamonds, joined spirals, arrows and heptagons. All of these shapes have meanings that come from pre-Columbian times and are associated with Andean cosmovision or worldview: their deities, worship of the Earth Mother or Pachamama, conceptualization of time and space. Some patterns also record historical events that persist in the collective memory of the community.

The large diamond symbols at the center represent a relationship to female fertility while the S-shaped spirals relate to the universe. Other woven representations that endure today depict the execution of indigenous rebel leader Tupac Amaru II and the foretelling of his millenarian return, with four horses quartering Tupac Amaru II and four condors pulling apart the horses.

Woven textiles were an important measure of social and economic status, and played a central role in civil and religious ceremonies. Everything from the spin of the yarn and the symbols woven into the textiles, to the colors used and techniques employed, conveys meaning about the weaver and the community.

Both men and women in Andean communities spin yarn, and children start to learn to spin around six years of age. Use of contrasting colors allows weavers to create patterns of repetition, contrasts, juxtapositions, reversals, symmetries and asymmetries, as well as use of negative space to encode meaning and communicate a worldview.

The kallwa or beater is a weaving tool designed to push and compact the weft yarn into place. Size and weight varies depending on the dimensions of the tapestry and thickness of the yarn.

These small textiles, known in the local Quechua as ukhuña, originate from the town of Chinchero in the Cuzco region of Peru. They are used in traditional ceremonies such as the pago a la tierra and are often worn on the back. While the woven patterns are typical of local textiles, the blue and red blocks are especially representative of Chinchero. Also note the intricate woven borders on each example, referred to in Quechua as awapa (the edge).