Walking through England, there are museums, monuments, and historical sites everywhere you look. When I visited the Imperial War Museum, the Churchill War Museum, and Bletchley Park I found them to represent history in completely different ways.

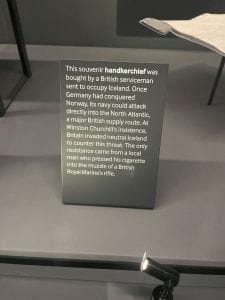

The Imperial War Museum was immense and it displayed a lot of items and descriptions for soldiers from England, soldiers from Germany, families at home, and so much more. I feel like every corner I turned, there was a new gas mask or uniform I was looking at. One room was built to look like the inside of a house. It’s wallpaper showed pictures of families wearing gas masks, pictures of kids playing, and pictures of soldiers. There was a fire flickering in the middle of the room, and a radio next to that. The radio was playing an old broadcast that was talking about the war, but it was hard to make out exactly what the voice was saying. As I was walking around it was insane to imagine that this was how people lived for six years. Leaving the house, there was an air raid shelter that I was able to squeeze inside. I wasn’t even able to stand up straight while I was in there. Right outside of the shelter was a display showing all of the bombs that might have been dropped on the fake home I was just in which was chilling to imagine. The Imperial War Museum explained so many different topics by trying to have them be as relatable to viewers as possible, and walking around really showed me a lot of different perspectives of the war. It it helped me understand just how many different perspectives there could have been during the war, whether that be that of a soldier, or that of families sheltering in place at home.

Opposing the broad perspective of the Imperial War Museum, the Churchill War Museum focused completely on Churchill and the behind-the-scenes of planning the war. In all of my history classes we have always talked about important people meeting in a room to discuss big plans for the war. I don’t think I completely understood the work that went into planning such complex things as war until I was able to walk through the war rooms and hear workers from this time talk about their jobs and experiences. There were maps that took up the entire wall that had lines and pins scattered all over them showing where troops from both sides were. There were statistics posted everywhere showing casualty rates of both friend and foe, and every wall that surrounded me was covered in paper. I can’t even comprehend the amount of work that went into keeping such accurate information and deciding which information was important enough to be posted. In addition to looking around, I was listening to an audio guide that was explaining what I was looking at. When first person accounts started playing of the people that worked there it showed me everything in a new perspective. So many of the rooms had typewriters and beds in the same space. Listening to a woman tell me how she would wake up, start working and continue working all day, only to go to bed and repeat the same process the next day told me exactly how dedicated everyone involved in the behind the scenes of the war was to this cause. This museum was a lot more specific to what kind of work these people were able to complete and how it helped the outcome of the war overall.

Bletchley Park was similar to the Churchill War Museums in how it focused primarily on one thing, which in this case was codebreaking, but it differed because it explained how the workers did their jobs. Bletchley Park focused on explaining the Enigma machine, and all over the park there were little interactive games that explained the process of codebreaking. The first thing I saw when I walked into the museum was what looked like a little gear. I found out that this “gear” was actually a ring of letters that made up a rotor. This rotor was then set to a certain order of letters (depending on which code was being used) and there was a plugboard that lined up each letter typed to what the coded letter would be. Despite seeing the enigma machine being taken apart in front of me, I still don’t completely understand how it works. This helped me to develop a deep respect for those that worked here and understood such a complex concept. This respect was only grew because there were pictures of young women all over the walls next to explanations about how they worked all day every day to break this code, yet they couldn’t let anyone know what they were doing. They were about my age, or even younger which completely blows my mind. This museum was different because it explained the process of how information was gathered and how workers did their jobs instead of simply explaining the overall effect this work had on the war.

These museums represent history in completely different ways, but I find this valuable as it shows how there are many ways to view a national war. Every single person has a different memory of WWII, and seeing so many different museums has let me start to understand that the collective memory of WWII is insanely varied. Depending on what your experiences were or what you’re focused on studying, you can view WWII completely differently than someone else which I has made me love learning about it even more.