During World War II, the Vichy government in France collaborated with the Nazis. It deported people to concentration and death camps who were considered unworthy of living as well as accommodating other needs of the Nazis. This bit of history is learned when a student starts studying World War II in depth, but when students are taught about the war in middle school they are just told that it only took six weeks for France to fall to the Nazis and that is the end of the lesson. What I found in France is that the museums pretty much stop there too and move on to D-Day.

On May 15, we went to the Caen Memorial Museum. The museum started off with a downward spiraling staircase taking us through the years leading up to World War II. The downward spiral is supposed to symbolize the world’s descent into hell as Nazi Germany gained more and more power. Then came the section on the invasionn of France. This part of the museum made me feel like I was being geared to pity the French much more than I normally would have. It was dimly lit with pictures of recently homeless French children and dead soldiers. Having studied World War II in depth for the past four months, it was easier for me and most of my classmates to pick up on the manipulation of the museum.

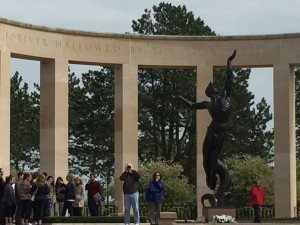

A photo also displayed at the Caen Memorial Museum. This photo depicts that the French people were lively and happy, and then suddenly surrounded by the Nazi forces out of the blue.

Then the museum had a very small section on the Holocaust. It displayed the basic information that most people already know about the Holocaust. It had said that the Germans were systematically killing Jews and others in an effort to exterminate undesirables. However, there was absolutely nothing in the museum about how the Vichy government, under the control of Marshal Pètain, helped deport people from France for the Nazis. In fact, there was nothing in the Caen Memorial Museum or any museum we travelled to in Normandy or Paris that even mentioned the Vichy government.

I have learned in these past months that the French government ignored the Holocaust for a few years when the war ended. It is evident that the French government knows it made a mistake in doing this, but I found a quote in the Caen Memorial Museum that almost excuses the lack of action from the French government: “It took some time, however, for comprehension of what had been happening to sink in, given the near impossibility of grasping a reality so monstrous that it seemed inconceivable to those alive at the time.” This was at the very beginning of the Holocaust section of the museum. This quote is blatantly excusing the French government for ignoring the Holocaust for so long.

There is a similar pattern in most governments where the state barely acknowledges something they did wrong if it is acknowledged at all. I have yet to see information in a museum about the Japanese internment camps that were set up in the United States after the bombing at Pearl Harbor. Children are told that Thanksgiving was a time when the Pilgrims and Native Americans shared a dinner when they finally settled their differences. In reality, it was a celebration thrown on by a hand-full of colonists after they massacred an entire tribe of Native Americans.

Another student mentioned during a reflective talk that he would have preferred to be left with questions after having received all the facts instead of having questions because of a lack of facts, referring to the museums we have seen. This moment just keeps reoccurring to me because he was one-hundred percent correct. Without all of the information, there is no logic in drawing conclusions about a specific topic, especially one about a serious blunder made by a government. The museums in Normandy and Paris gave the impression that it is much better to forgive and forget than to actually discuss what went wrong and why. If we choose to forgive and forget, how will we ever learn from our mistakes?