We arrived to France by ferry. The first day we settled into the hotel. It had been a long day, and after being away from home for a week Brittany Habbart, Chris Herrel and I were craving American food. So, we went to the one place I never go to at home – McDonalds. It never tasted so good.

The next day we visited the Museum of War and Peace. This museum commemorates World War II and the Battle for Caen. It is dedicated to the history of violence and conflict in the 20th century. The museum opened on 6 June 1988, the 44th anniversary of D-Day. The thing I noticed most about this museum compared to other museums I have visited is that it consist of much more reading. I thoroughly appreciated the information given. Instead of having a simple excerpt pertaining to a piece in front of you, the museum was organized in chronological order providing the main details of the war.

Our next stop was Pegasus Bridge. Pegasus Bridge, originally referred to as the Benouville Bridge, was built in 1934 across the Caen Canal. In World War Two control of the bridge was the objective of Operation Deadstick. This operation was in preparation for the Allied invasion of Normandy. Control of the bridge was imperative in limiting the effectiveness of a Germany counter-attack following the Allied invasion. The bridge was renamed in honor of the soldiers who captured it. Today, a replica stands in its place, while the original bridge is now displayed in a museum.

As we made our way to Utah Beach we made a stop at the Statue of Major R.D. Winters. Winters was a solider of the United States Army. He commanded Easy Company of the 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, part of the 101st Airborne Division during WWII. Easy Company parachuted into Normandy early in the morning on D-Day, June 6th, 1944. Their objective was to capture the entrances to and clear any obstacles around the route selected for Allied forces. Immediately issues arose. Winters and his men landed without a single weapon. Easy Company were using British designed leg packs, which held their belongings and weapons. As soon as Easy Company jumped the packs were torn away. Easy Company landed completely unarmed. Even so, Winter’s and his company charged on, securing the way.

Utah Beach was the code name for one of the five areas where the Allies invaded German-occupied France on D-Day. It is located on the Cotentin Peninsula. Amphibious landings were undertaken by the United States Army, with support of the United States Navy. The objective was to secure the beachhead, the location of the vital port of Cherbourg. We spent some time at the Musee du Debrquement de Utah Beach. This museum detailed and highlighted some of the important parts of the Normandy invasion at Utah. Throughout the museum were some personal articles, such as letters, from soldiers displayed. Personal items are always my favorite. Most of these men and women fell in combat. I think reading there personal letters is the closest we could ever come to the mindset of the men and women who gave their lives. It’s incredibly humbling.

We made a quick stop at St. Mere Eglise. It’s a small town that witnessed some of the first fighting after the D-Day invasion. It was one of the first towns to be liberated. While in town we made a stop at the Musée Airborne. This museum is dedicated to the memory of American paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st airborne divisions who parachuted into Normandy on the night of June 5th and 6th of 1944.

We ventured on to Angeoville au Plain Church. This church was used by 2 US Army Medics, Robert White (a fellow buckeye) and Ken Moore of the 101st Airborne, as an aide station during the Battle of Normandy. White and Moore treated 80 injured soldiers, American and German. The story behind this little church is amazing. Two men came together and saved the lives of not just their comrades, but their enemies. To them the injured were not G.I.s and Nazis, but simply men in need of help. Robert White survived the war and passed on some years ago. Half of his ashes are buried on the church grounds, the other half back home.

Our last stop of the day was the German cemetery. This cemetery contains roughly 21,000 German military personnel of World War II. As staggering as that number is, it is not the only Germany cemetery of WWII causalities. The cemetery, as all are, was sad. The layout of the cemetery, together with the dark grave stones and simplicity, made the experience harrowing. Seeing grave stone after grave stone, most the final resting place of two men (as space was limited), was overwhelmingly depressing. At the center was a mound of the unknown. This is the resting place and dedication to those dead who were unidentifiable. That was the most heartbreaking. So many families were never given an answer to the fate of their loved one. So many of the fallen are never to be known. Something that I thought of while walking the grounds is the idea that while these men were on the wrong side of history, they were fighting for their home. The Nazi regime rained hell upon Europe, claiming so many innocent lives. But the men buried here, these soldiers, were not all fighting for Nazi ideals, they were fighting for their home and their family, others forced into service. Most of these soldiers were my age, many younger. They were left with an unbelievable burden and deserve to be remembered.

The next day we visited Point du Hawk, Omaha beach and the American cemetery. Point du Hoc is a promontory with a cliff overlooking the English Channel. The German army fortified the area. On D-Day the United States Army Rangers were tasked with the objective to capture Point du Hoc to ensure that the German 155m guns would not threaten the Allies during the invasion and to prevent the Germans from using the area for observation. Omaha beach, another area of the Normandy coastline invaded on D-Day, had a heartbreaking story surrounding the fates of the “Bedford Boys”. Company A of the 116th, a former National Guard unit, was comprised of 35 men from Bedford, Virginia. Company A participated in the initial wave invading Omaha and was slaughtered. With war, these sort of casualties were not uncommon. However, what is so devastating is that Bedford, a town so small that everyone knew just about everybody, began receiving telegrams informing families about their loss one after another. A total of 22 young men lost their lives. Everyone in Bedford was affected by the devastation.

The American cemetery, which overlooked the water, was beautiful. The thing that stood out to me most, which I thoroughly appreciated, was that while a theme of the cemetery was uniformity, those who were of the Jewish faith were buried with the Star of David as the headstone, not a cross. The cemetery remembered the men lost in typical grand American fashion and highlighted the cause for which they fought. A quote that is located inside the accompanying museum by the doors which leads to the cemetery sums it up quite well – “If ever proof were needed that we fought for a cause and not for conquest it could be found in these cemeteries. Here was our only conquest: All we asked…was enough soil in which to bury our gallant dead.” (General Mark W. Clark)

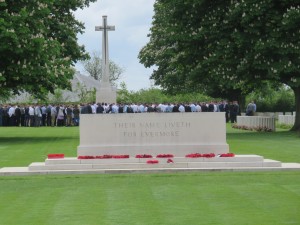

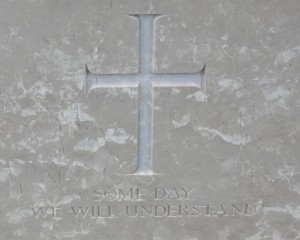

The next day consisted of the Bayeux Tapestry, the Arromanches 360 Theater and the British cemetery. The Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered cloth nearly 70 meters long depicting the entente leading up to the Norman conquest of England, was interesting. The museum that accompanied it, not so much. We saw a short video at the Arromaches 360 Theater that I found intense. The theater overlooks the water where several Mulberries, or artificial harbors, are located that were used during the D-Day invasion. The British cemetery was our last stop. It was my favorite out of the three. The graves in the cemetery were personalized with an inscription picked by the family located at the bottom of the grave stone. This personalization made the tremendous loss of life much more real. The surrounding area, just like the German and American cemetery, was beautifully sad.

Our last day consisted of a day trip to Mont. St. Michel. I was very excited about this. Mont. St. Michel is an island commune in Normandy, France. The island is home to a monastery which bears the same name. The position of the island made it accessible to pilgrims during low tide. During high tide the island was nearly impenetrable. Today, the abbey is home to a handful of monks and nuns.

We were in Bayeux for about a week. The quaint little town was beautiful, almost like it was straight out of a storybook. Our next stop in France was Paris. I loved Paris. I hope I’ll be able to come back one day. We were there for just a few days and it was most certainly

enough.

While in Paris our group visited the Memorial de Martyrs de la Déportation and the Musée de l’Armée. The memorial was my favorite stop in Paris. The memorial is dedicated to the 200,000 people who were deported from Vichy France to the Nazi concentration camps. What I appreciated most was the inclusiveness of the memorial. European Jewry was by far the most devastated by the Nazi regime. However, I think it is important to remember that not all victims were of the Jewish faith. The memorial does not simple recognize the deportation of French Jews, but all those who were deported under the Vichy regime.

What I took away most from my time in France are the various ways the war is remembered. In the United States it was the “Good War.” Our cemetery is grand and beautiful. American boys fought and died for people they have never met and never would meet. The British cemetery was personalized and very much representative of the “People’s War.” The German cemetery on the other hand, while peaceful, was very dark. I feel as if Germany rightly so remembered their dead and remembered the destruction it caused. The difference, however, between the German cemetery and the American and British, is that it did not remember the cause. The American and British cemetery highlighted that the soldiers lost their lives defending the ideals of freedom, while the German cemetery did not emphasize Nazi ideals. Instead, they highlighted each individual man whose life was cut short.

t had sets of 5 crosses placed sporadically throughout with a large monument in the middle. This site did not seem to be well traveled and had a very somber feel to it. Aside from the lack of people, the small brown graves that were embedded in the ground made the area seem much more open and empty. These graves were also generally honoring two soldiers which added to the magnitude of death that could be felt there. Walking into the American cemetery overlooking Omaha Beach, I was struck by how large it was. There was row after row of white crosses that I think accurately depicted the destruction that the soldiers were faced with during the beach landings. The memorial at the beginning of the museum depicted a muscular man with his arms outstretched.

t had sets of 5 crosses placed sporadically throughout with a large monument in the middle. This site did not seem to be well traveled and had a very somber feel to it. Aside from the lack of people, the small brown graves that were embedded in the ground made the area seem much more open and empty. These graves were also generally honoring two soldiers which added to the magnitude of death that could be felt there. Walking into the American cemetery overlooking Omaha Beach, I was struck by how large it was. There was row after row of white crosses that I think accurately depicted the destruction that the soldiers were faced with during the beach landings. The memorial at the beginning of the museum depicted a muscular man with his arms outstretched.