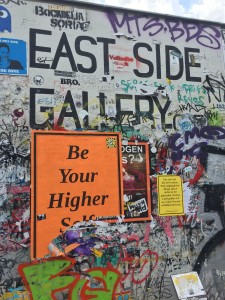

The first thing I saw when approaching the East Side Gallery. This is near the edge of a piece of the Berlin Wall that still stands.

The East Side Gallery is long and winding along the Berlin Wall. When we got there, the day was hot and sunny, and the city was alive with people. There was a train station near the gallery that undoubtedly left off many interested in viewing the art. There were many restaurants on the streets near the Wall and their smells wafted over to those walking past. As we approached the Wall on our left, we could see it curving far into the distance. It stretched forward as a lengthy testimony to the past and the present, and baring prophecy for the future.

The East Side Gallery is a long stretch of the Berlin Wall that remains up in the middle of Berlin. Artists have come for years to paint whatever they wish on the Wall, each getting a section to call their own. A fence protects a lot of the art, not even it is protected from the ubiquitous graffiti of the city. The top is high, seemingly at least ten feet when looking up at it, a testament to oppression. It is because of the Wall’s oppressive history that the art seems so appropriate; expression rightly covers repression.

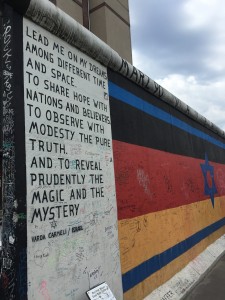

The first writing I encountered on the Wall. This text mentions dreams among other texts and pictures along the Wall.

The Wall looks like it was made of cement and is quite thick, seemingly around six inches. But amazing art covers much of the cement, and now, there seems to be more bright color than the dull gray of the original Wall. There is some writing on the Wall among the pictures and designs. One of the first things written that we came to said “Lead me on my dreams among different time and space.” Dreams seemed to be a reoccurring theme at the wall. Perhaps the Wall held in dreams for so long that it was inevitable that it would be decorated in dreams once that was allowed.

The painting of colorful, futuristic-looking gas masks on the Wall. War seems to be a common theme in the Gallery.

Not far into our walk we came upon a painting of gas masks. They were blue, yellow, red, and black and looked futuristic. Their tubes were twisted and knotted. The masks were disembodied, but strange and darting eyes appeared in their openings and were unnerving. War, death, and destruction were other common themes of the Wall. Perhaps that too is appropriate for a Wall built in the mounting tensions of the post-World War II world. It seemed further appropriate for a wall maintained in an age of possible nuclear destruction. Like the shadows of people burned into the ground of Hiroshima, the Wall, in a way, documents the possibility of total annihilation.

A colorful painting on the Wall. Here, panicked people seem to curl into the distance in some kind of explosion.

The Wall is happy also, and vibrant and artsy. The art covers the ugly Wall beneath it and symbolizes a new nation and a new people, or perhaps an old people finally let loose from the fetters of oppression. The art is more than a mere mask though. It cannot simply fall off at any moment, caught in a brisk wind. The art is there to stay. Now, the only thing to replace the art is another coating of art. And I don’t think that would be a bad idea either. Just as nations and people built their culture and themselves upon the previous nation and people, the wall can built upon itself. New paintings could cover and use the paintings beneath them to create new things. Just as the German people are built now on the Cold War generation, and the World War II generation before them, they will continue to build. In fact, the Wall as a medium is kind of the first painting in itself. The first layer of art is only the second painting, and happily a more colorful and expressive one. The art and the Wall carries repression and dreams, real and prophetic death, art and artlessness. And the Wall carries on it Berlin and its people. I think maybe every city would do well to find its Wall, whatever that may be, and begin painting. The layers of the past don’t need to be permanent. Art can always cover the dull gray Wall.