Berlin’s a pretty forward place. And I don’t mean modern, though it certainly is. I mean forward. There’s no beating around the bush or hiding the past. Not anymore, anyway.

I’m given to understand that after the War, Germany didn’t know quite how to feel about the whirlwind it had just been through. Lucky for Germans, their country was thrust straight into the Cold War, so they had other things to worry about. But this all meant that for years, Germans couldn’t face their Nazi past. There was no dialogue and no honesty, only trepidation and nagging discomfort.

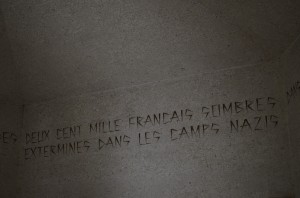

Decades later (especially after the reunification), Germans began to talk a bit more openly about their experiences during the War. From what I can tell, the way they talk about their War embraces all of the moral uncertainty and guilt that comes with it. They are acutely aware of the murder that their parents and grandparents either committed or helped. But they’ve collectively decided that the only way to deal with such guilt and disillusionment with national identity is to talk about it. And they do: every tour guide I’ve had here and every museum I’ve been to have mentioned German atrocities during the war, and not just ones committed by the Nazi regime. There’s plenty of talk about civilian complicity. And though it would be easy to make excuses for the Germans’ behavior during the war, they don’t. By law, by convention, or by determination to end hate, they force themselves and everyone else to remember.

The most powerful example of this that I’ve come across is Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. It’s a massive grid of gray concrete blocks sitting smack in the middle of Berlin. It’s impossible to ignore, probably by design. Even the name is matter-of-fact: It’s not just to the victims of the Holocaust; it’s to the Jewish victims who were murdered.

What I like about the Memorial is that it’s interpretive. It doesn’t put a clear face or name to those slaughtered by the Nazis, which forces you to think about the victims and what they went through. Or maybe it forces you to think about why exactly the Holocaust is so important to remember. Either way, the Memorial stands as a constant reminder and thought-provoker to everyone who passes it. Here are some of my thoughts, which I jotted down as I walked through the site:

– The Memorial, like the Holocaust, is systematic, deliberate, and organized.

– It’s enormous, but one can’t really grasp its size except from the outside. I think this is similar to how it’s difficult to perceive the enormity and terror of the Holocaust except with the benefit of hindsight and reflection.

– From the inside, it’s dark and somber, but when you look up, you see sunlight. Despite the darkness people are capable of, there’s always a ray of hope.

– The blocks are all of different heights, but they are of the same color. This reminds me of how the people murdered by the Nazis were of so many different backgrounds, but were the same in that they were unwanted (by virtue of their religion, nationality, mental ability, etc.).

– It’s a collective memorial to all of the Jews killed. I interpreted this as a reference to the mass graves in which so many Jews were buried during the Holocaust. The only difference is that the Memorial has individual blocks, almost like gravestones. Maybe this is an attempt to honor each individual killed.

– There’s no rhyme or reason to the direction in which you walk through the Memorial. I read this as a reference to the lack of any sense or logic behind mass murder and hatred.

I could keep going with the interpretations, but that seems adequate to describe what the Memorial means to me. Obviously, I have no way of telling if any of this is what the designers actually intended, but I like that the thoughts that the site stirs are deeply personal.

I wanted to feel sad when I visited the Memorial. Sorrow is the only emotion that really feels appropriate to me when it comes to remembering the Holocaust. I can’t help but think about how had my family and I been alive at the time, we would have been, by law, subordinate and unwanted. I can’t imagine how I would have coped with a life of fear and violence like that. And it pains me to think of those millions of people who suffered and died because they were different.

For some reason, I didn’t feel pure sadness at the Memorial. I couldn’t put my finger on why, but I think there was a sort of comfort in knowing that an entire nation had put so much thought and energy into memorializing something so important to me. After I’d spent about twenty minutes standing in the center of the grid, I tried my best to get exactly what I was feeling on paper. Here’s what I wrote:

“[It] does seem almost hopeful. I’m not fully sad here, weirdly. It’s stark, and it’s striking. It makes me want to remember all those people. My people. I didn’t know a single one of them, but they stood like stones in the face of certain death. I’m proud to be one of them. What an odd thing to feel Jewish pride at a Holocaust memorial. But I’m proud. I’m deeply sad; moved. But always proud.”

It shouldn’t have taken 11 million murders for us to realize how poisonous it is to hate people. But it did. So let’s follow Berlin’s example and keep talking about the Holocaust. Let’s remember it for the torture and violence and destruction and slaughter it was. Let’s never, ever forget.