Out of all of the cities in the program, I was the most excited for Berlin. My family has German roots, I took German language classes at Ohio State, and my focus of study the past semester was the Nazi Regime. Having studied Berlin’s past and present during my first two years at Ohio State, I felt that I would learn more from Berlin than some of the other cities. I was not disappointed. As I write this post I am sitting in a hostel near Alexanderplatz, a hub of transportation and shopping in the Mitte district of Berlin. I will be sad to leave this city in the morning, but I know that I will return in the future.

Out of all of the cities in the program, I was the most excited for Berlin. My family has German roots, I took German language classes at Ohio State, and my focus of study the past semester was the Nazi Regime. Having studied Berlin’s past and present during my first two years at Ohio State, I felt that I would learn more from Berlin than some of the other cities. I was not disappointed. As I write this post I am sitting in a hostel near Alexanderplatz, a hub of transportation and shopping in the Mitte district of Berlin. I will be sad to leave this city in the morning, but I know that I will return in the future.

I absolutely fell in love with this city. Every aspect of Berlin left me wanting more. Being surrounded by the language, and being able to pick up some of it, was extremely satisfying. Navigating on yet another public transit system was challenging, yet very rewarding. The walls and buildings here are covered in graffiti, but the graffiti didn’t make me anxious or alert like it would in Cleveland or in Chicago. In Berlin, graffiti is part of the city. Here it is viewed as art rather than a signal to move to a more populated and well-lit area. It gives the city character.

My favorite thing about European cities is being surrounded by history. I definitely found this in Berlin, but the history around me was much different than that of London or Paris. It is not unusual for buildings in London or Paris to be hundreds of years old. Many of the structures in Berlin are more reminiscent of the 1970’s or 1980’s. The city looks much younger than other cities we visited, but there are still structures like the Brandenburg Gate or Berlin Cathedral Church that gives it the feel

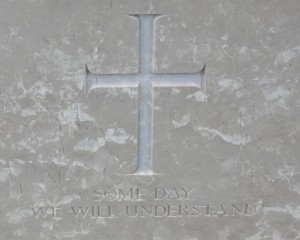

of an old city. Berlin was subjected to 363 air raids during World War II. As a result, a massive number of buildings were destroyed. Following the war, Germany was divided into four sections. Berlin was also divided into four sections. When the Berlin Wall was put up in 1961 the city was split into East Berlin and West Berlin. The country of Germany was also split into an East and West side. Walking through the streets today I sometimes have a difficult time figuring out if I’m on the East or West side, but several pieces of the wall are left standing as a reminder to the city and its visitors. In addition, different colored pavement and brick runs along the old boundary of the wall. Plaques are placed along this line which read, “Berliner Mauer 1961-1989.” Last night on my way to my hostel I had to cross this line. Thirty years ago I would not have been able to casually roll my suitcase over that line. The city seems to have come a long way since the end of the war and since the reunification of 1990.

What was most interesting to me about Germany is the manner in which it handles its dark and complicated past. In France, the museums refer to the Germans or the Nazis as being responsible for the horrors of the war. They seemed to quick to place blame on Germany and they do little to acknowledge their hand in the Holocaust. They reduce Vichy to seem like it was just a few bad apples who made poor decisions. After being disappointed in the French, I was anxious to see how Germany would present the events of the war. In contrast to the French museums, the German museums didn’t obviously try to manipulate the way visitors viewed their part in the war. The history was presented in a matter-of-fact manner. It neither took nor placed blame. The German museums very bluntly stated exactly what had happened without loading the presentation with emotion. I found this to be a constant theme through the museums I visited during my time in Berlin. Even the Hamburger Bahnhof, a contemporary art museum I visited, had a section dedicated to “Die Schwarzen Jahre” (the black years) which places art praised and denounced by the Nazis side by side for viewing and critique. The Germans present the facts, and allow others to form their own opinions and questions based on those facts. As a student of history I greatly respected this approach. With their dark history I can’t imagine it would be easy to take the blame, but they are working to move forward rather than dwell on the past. Most notable to me is that the schools require their students to visit a certain number of war or Holocaust related sites during the time they are in the school. To me, this is a prime example of Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms with the past). By including their more recent past in school curriculum, Germany is acknowledging the problems of the past and working towards a stronger Europe through their youth.

As I leave this city and end the program, I carry with me a deeper understanding and appreciation for all sides of World War II and the struggles to rebuild and deal with the aftermath. I have seen and heard perspectives and methods of coping that could not be done justice in a text book. I’ve been reminded how our history doesn’t necessarily define us, but helps us to grow and move forward. I’ve opened myself up to new experiences and ideas, and I think this will greatly help me when I return to Columbus to start my junior year at The Ohio State University. I cannot express how grateful I am for the experiences I’ve had over the last three weeks. I’ve gained more academically and personally than I could have ever imagined. I will leave Europe a more confident person with friends who are more like family, and professors who have become mentors. This adventure was truly once in a lifetime and I can’t wait to use what I’ve learned to impact my community and my future approach to historical study. My expectations were shattered, but what I ended up finding was so much better.

Auf Wiedsesehen,

Bailey