We walked through the gates of the German military cemetery in Normandy and it stretched out in front of us. The manicured, grassy lawn was interrupted from place to place by small, short gravestones that marked the dead. The markers were simple, evenly sided stone crosses on top of square cement slabs. The epitaphs bore witness to one or two names and their respective dates of birth and death. Many inscriptions read only “Ein Deutscher Soldat.” At varied intervals throughout the cemetery, five crosses, side-by-side, dotted the grass. Two shorter crosses were on either side of a taller cross, but all of them stood taller than the unimpressive gravestones. There were no flowers except for the small, appropriately simple wildflowers that sprung up graveside in the grass. Trees shadowed many of the graves. In the center of the cemetery, a large earthen mound rose up as the place’s only impressive structure. Around the base, small metal plaques marked the names of more of the dead. The mound was topped by a large gray cross, and two solemn-looking figures stood beneath the cross’s wings. The place was very quiet, and there were few visitors present to pay their respects.

A German grave with a set of five crosses behind it. In the background, the cemetery’s mound can be seen.

To me, the cemetery’s distinctly simple design seemed to have meaning. There were no grandiose structures, no walls with quotes to show the sacrifice and valor of the dead, no flowers to supplement the stone, and no words, save their names, to mark the soldiers’ resting places. The entire design seemed to plea with visitors to respect the dead, though not their cause. The simplicity of the place distanced the soldiers from the grand plans of the Nazis and the incredible persona of the Fuhrer. The soldiers were made, through their graves, into simple soldiers, simple people, who died the same death as any other soldier regardless of cause. And the many crosses of the grounds tie the German soldiers there to soldiers of various other nations around Normandy. The cemetery states that just as American families

The steps leading to the top of the mound in the center of the German cemetery. The backs of the figures under the wings of the cross can be seen at the top.

have found asylum in their sons’ crosses, so too can German families; just as American soldiers can find rest in heaven, so too can German soldiers.

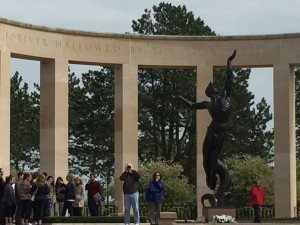

The American cemetery in Normandy offers a different picture. As we walked into the cemetery, we passed through a large stone-surfaced area. The back of the area had a columned arch that declared the eternal honor due the dead who were sacrificed in a campaign to uphold basic human ideals. In the center of the area was a large, black statue of a man looking up with his arms outstretched toward the sky. The statue seemed to represent the Allied cause, embodied in the dead American soldier, a cause which upheld the ideals of a free world. Down steps, we saw a large, dark pool of water, and passed that two tall American flags rose. Next were the graves, a seemingly endless sea of white crosses and six-pointed stars. The epitaphs told the soldier’s name, division, home state, and date of death. Well-kept trees and flowers surrounded and dotted the grounds. A small, domed chapel was in the center of the graves. There was a view along one side of the cemetery to Omaha Beach below and the ocean beyond. The place was busy with people, and a ceremony was ending when we arrived. Many Americans were there, but I also saw groups of people from France and Great Britain. Many faces looked indifferent, even happy, but others were solemn, even tearful.

The cemetery gave the impression, by stating it as fact, that the American fight was a just fight. The American dead were made into heroes and martyrs. The location of the cemetery also encouraged the idea that they were liberators. The graves sat high above the beaches, many marking those who died taking that very sand. The arch discussing just ideals, the crowds, and the white crosses looking down at the beach seemed to validate that those buried there had liberated that place. They had been selflessly sacrificed to regain France’s freedom.

The tall, black statue at the front of the American cemetery. The arch declaring the sacred ideals of the Allied cause is behind the statue.

But the cemetery also worked to dehumanize the dead. Of the waves of graves, there were only two designs, and most were the same white cross. The American soldier’s grave, and thus the American soldier, became mass produced. The graves looked as if they had come straight off the assembly line. The soldier became a tool of efficiency, quantity, and replaceability. There were no personal epitaphs or tombstones. The soldier’s epitaphs all seemed to become that of the arch that declared the ideals of the Allied cause. And the soldiers all became the large statue that held up those ideals. The white crosses became small, just footstools for the statue that watched over them. The soldiers, or the entire military, became Atlas, the weight of the world had fallen upon them, and they had held it high. The white markers seemed to be mere twinkles in Atlas’ eyes, necessary, tragic, and heroic.

The British cemetery was different still. As we walked through the entrance a green lawn stretched back into the distance, baring about a third of the way back what resembled a gray tomb with the words “their name liveth for evermore.” On either side of the tomb was a columned mausoleum-like building, and hanging, purple flowers snaked and drooped around the columns. A large gray and black cross rose up another ways back, the tallest monument of the cemetery. Graves rose around these structures in rows, many of which were skirted in various flowers and covered in trees’ shadows. The gravestones were all the same shape, and they were designed with a cross, six-pointed star, or neither, as well as the insignia from the soldier’s fighting force. The gravestones also indicated the soldier’s rank, name, date of death, and age. At the bottom of the stone, most of the graves had a personalized epitaph picked by the soldier’s family. The cemetery even had graves for war dead from such countries as Germany, Canada, and the United States.

To me, this was a cemetery for soldiers, but even more, a cemetery for people. The dead were not exalted to lofty ideals and not degraded to sorry soldiers who died hapless deaths. There was not the same exclusivity that the German and American cemeteries had. Personal notes and flowers adorned the graves similar to civilian cemeteries. Though the cemetery was unmistakably a military one, these things made it feel more personal, and to me, almost more sincere. The cemetery seemed to convey that the people buried there had signed up, or were drafted, to fight, not to die. It seemed to say that while in death they remain forever part of the military and its cause, they return to their family and friends in memory and mourning where they truly belong.

Matt McCoy