When studying the history of war, it is easy to think in terms of numbers. It’s cleaner, and there is a lesser chance of emotion clouding your analysis. In a manner of speaking they allow you to desensitize yourself. In books, war is often presented in statistics. For example, approximately 156,000 Allied troops landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944. By the end of June 11, more than 326,000 troops had crossed the English Channel. I read a great deal in preparation for this trip, but the difference between reading and being there is that when you close the book, you can walk away. Being in Europe, you can’t turn away. The memory and consequences of the war are everywhere I turn. Numbers make it easier to try to comprehend the enormous manpower, effort, and sacrifice that go into war. However, I am quickly learning that easy isn’t necessarily better.

Walking into the sites of D-Day was incredibly haunting. I stood where so many made the ultimate sacrifice, but if there had been no markers I would never have realized where I was standing. The beaches looked just like any beach, which made them all the more haunting. It was as if the tide had washed away all evidence of what had happened. Omaha and Utah beach both seemed almost peaceful. I appreciated the opportunity to be able to stand there and take it all in, but it didn’t have the effect on me that I had expected. I was expecting to be overcome with emotion and sadness. Instead, these things hit me where I least expected it: in the three cemeteries

We visited the German, American, and British cemeteries (in that order) during our time in Northern France.

The German cemetery was very well manicured and appeared much older than it actually was. The German cemetery was the least individualized out of the three I saw. There were grave markers rather than headstones, and 2-3 men shared a marker. On the marker was written a name, and the dates of birth and death. A large mound was placed in the middle of the cemetery to represent the old burial mounds. The mound was topped by a cross and the figures of what I believe to be Mary and Jesus. There was a small visitor’s center, but it was across the road and its style was slightly outdated. As in life, the Germans seemed to be almost mechanical. Even in death, they didn’t seem to be their own person.

The American cemetery was the most moving for me. Before entering the cemetery, we went through a Visitor Center which detailed the war and the lives of those who fought it. The exhibition centers on the themes of competence, courage, and sacrifice. The walls were covered with the names of fallen soldiers and their life stories. There was a section of the museum where you could search for specific people by name to see if they were in the cemetery or where they were located in the cemetery. Most striking to me was the room of sacrifice near the end of the center. Until that point I was able to maintain my composure. To enter the room, you must pass through a tunnel. As you walk through the tunnel, you can hear a voice announcing the names of those who were lost. The reading of names is still audible as you enter the large white room to read the stories of a few who exemplify sacrifice. As I read and viewed the pictures of the fallen soldiers, the gravity of what I was actually viewing began to set in. The American cemetery seemed more geared towards keeping the memory of the fallen soldier alive rather than laying it to rest like in the German cemetery. Each person was given their own headstone. As I moved into the cemetery I could see that Christians had a cross, and Jews had a star of David as their marker. Each marker was engraved with a full name, rank, division, home state, and date of death. On the back of the headstone was the dog tag number of the deceased. The three Medal of Honor recipients had their information written in gold. On the stones of the unknown was written, “Here rests in honored glory a Comrade in Arms known but to God.”

During my time in the cemetery I had the honor of planting an Ohio State University flag at the grave of Private John O. Fry Jr. Fry was a student at the university, and died on July 27, 1944. He was a recipient of the Silver Star and the Purple Heart. I’m disappointed that so far I haven’t been able to find more information on him. Being face-to-face with his grave really put things into perspective for me. So many of these men were my age when they died. Fry went to my university. These people are buried across an ocean, and many of their families are unable to visit their graves and gain closure. It’s overwhelming. Everywhere I turned there were more headstones. I left feeling solemn and saddened, but much more appreciative for the life I have.

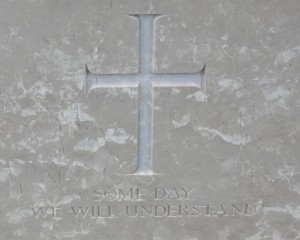

Families of fallen soldiers had the option of engraving stones with a message. I found this one particularly striking.

The last cemetery we visited was British. There was no visitor center, and while beautifully manicured, the cemetery didn’t feel nearly as formal as the other two cemeteries. The British cemetery is not exclusively British. There are many graves belonging to people of other nations. To me this expresses that at the end of war, all parties have lost their sons and brothers. In death there shouldn’t have to be separation between nations. All lost their life fulfilling their duty to their country. These headstones are intermixed with the British stones, but they are all different shapes depending on the nation, and the inscriptions were different than the ones on the British stones. The British stones included a name, rank, division, date of death, age, religious symbol, and in some cases a message from the family of the deceased. The stones belonging to the unknown said “A Soldier of the 1939-1945 War known unto God.” The messages from families were gut-wrenching. They ranged from short biographies to bible verses to the simple “Forever in our hearts.” Many messages were signed with “Love Mum and Dad” which for me really drove home how young these men were. Surprisingly, a large number of Germans are buried in this cemetery. Also surprising was the decision to refer to the war as the 1939-1945 War. I had never heard or seen it stated that way. Why would they decide to refer to it in that way instead of as World War Two or The Second World War? Calling it the 1939-1945 war makes it feel almost antiquated to me, like the 12 Years War or 30 Years War. I haven’t found an answer to this yet, but I intend to keep researching.

21,222 German remains are in the German cemetery at la Cambe.

9,387 American headstones are in the American cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer.

4,144 Commonwealth burials and 500 graves of other nationalities are in the British cemetery.

These are the numbers. Private John O. Fry Jr is one of those numbers. He was also a Buckeye, and more importantly a person. I will never view the numbers the same way again.

Bailey