What makes London London? How do you encapsulate a city like this? I absolutely loved Dublin… But with London, it’s as if every time I start to really appreciate it or figure it out, I find something imperialistic that makes me cringe. (Not to mention British royal history is really not my thing. I wilt a bit every time Laura gives me a new fact about the crown — love you, Laura). The whole narrative of British domination and empire makes me a little weary. That’s certainly not to say this is a new concept to me or that it’s entirely London-specific, because I wouldn’t exempt the States from this kind of critique, but I do think that it defines London in a unique way because the imperialist history is so much longer and it really rings through everything here. To me, London is a living embodiment of the empire that influenced it. And something about London’s feel as über privileged in its prestige and antiquity gives off a strange, constant condescension.

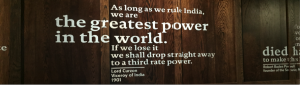

I noticed this most vividly for the first time at the Imperial War Museum. There was so, so much to take in, as the World War I exhibit had just been redone, but what I noticed most of everything in the exhibit was the centrality of India to England. In the first room of the exhibit, one quote amongst the other foundational information at the start of World War I really sent up a flag for me:

I was pretty surprised at the bluntness here, but the importance of the Indian subcontinent ran throughout the exhibit, including the fact that India provided the largest volunteer army in the entire war with 1.5 million men. The theme of empire wasn’t solely focused on India — the Ireland section was almost funny in the way that they spun it after having visited Kilmainham Gaol last week. During the Easter Uprising, the British secretly arrested and executed many of the top Irish leaders within a day on the grounds of the prison (the one I visited in Dublin, Kilmainham Gaol) where they mistreated many of the Irish men, women, and children who opposed British rule. But in the Imperial War Museum, there was a quick mention of the “Rebels” in the Easter Uprising and how “the brutal execution of the rebel leaders would fan the flames of Irish nationalism” (note that by whom wasn’t explicitly mentioned) after being tried by court martial, and then it moved straight into the Irish capitulation. That’s it. Nothing about the secrecy or Kilmainham conditions or… basically anything to make them look oppressive. They did have several handwritten notes from Pearse, one right after declaring Ireland a free state, which I’m sure Dublin would love to have in their own museum. That was independently offputting — there were a lot of crazy artifacts, which was neat, but why on Earth does London have the burned Torah scrolls?

On top of that, the responsibility aspect of the Holocaust exhibit was so odd. (This isn’t exactly imperialism, except when you add the Palestine equation and the possibility of increased asylum for Jewish refugees, but it’s a precursor to the issue of guilt that I find crucial). Throughout, the Imperial War Museum posted newspaper articles that outright listed the death tolls and atrocities. They appear to be exhibited as signs of how bad the conditions were, but they’re unintentionally a huge red flag of why they didn’t act sooner. These articles about the mass murders aren’t even making the front page (I checked. They’re on page eight.) — it isn’t even big news. But when you get to the part of the exhibit about liberations, they say that no one could have known the full extent before they saw the camps. In some ways, that’s certainly true — I don’t believe anyone could understand the full extent unless they lived it themselves — but at the same time, more than enough was known to do more than they did. I mean, opening borders for asylum should have been a no-brainer when it was all right in front of them no later than ’42. However, what threw me the most was the quote at the exit: something like “Evil will triumph whenever good men do nothing” (they wouldn’t let us take pictures, and I didn’t pen it exactly). I just drew a big question mark because the rest of the site had a total lack of responsibility. It wasn’t a blameless exhibit — there was plenty of information about the Nazis and even the Jewish Councils — so I couldn’t tell if it was a last-ditch effort to own it without giving any more detail, if they were continuing to pile on the Nazis, or if it was a strange burden shift that demeaned the resistance. I was baffled.

Once you see it, this presumed guiltlessness can be seen everywhere. It’s in other sections of the museum, too. In the WWII exhibit (which was largely underwhelming), ’33-’39 is just a brushstroke of Triumph of the Will and a couple of quilts made in Britain at the time. They skipped right over England’s role in appeasement. You can also see it in how they preserve memory elsewhere — for example, I ran past this fantastic, ornate, gold-laden statue of Albert (Victoria’s husband, for those like me who hadn’t the slightest idea) over at Hyde Park, which made me stop cold at the sight of this simple, drab pillar on a street corner near Wellington that mentioned the Indian subcontinent (as well as Africa and the Caribbean) and the five million men who lost their lives in the world wars. I tried to put together a side by side of the two, but they aren’t to size because the Albert one was on a pedestal and farther away, and I wanted to zoom as closely as possible to get the text on the pillar.

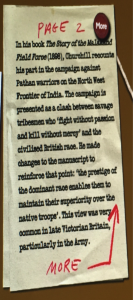

Seeing these back-to-back on my run really made the contrast hit home. I looked it up afterwards, and it turns out these pillars were the first permanent recognition of their sacrifice at all (as well as the sacrifice in the Caribbean and Africa), and it wasn’t created until 2002. This “voluntary” sacrifice seemed so underappreciated, and the lack of remorse for sending millions to their deaths for a crown that was forced upon them was screaming at me in the comparison in such a memorial-heavy city. The fact that this memorial in particular was so late veers toward the other theme of racial superiority that often goes hand-in-hand with imperialism, but in fear of this turning into a ten-page blog, I’ll limit this development to a couple of shots from the Churchill War Rooms (apologies for the quality between the two electronic screens):

Even without the racial connotation, the theme of empire that runs rampant throughout the city is unnerving in its unapologetic nature — as if they still don’t recognize that their actions were so problematic and damaged so many lives. Their pride in their empire is still their guiding force over the humanity that the pride so disparately impacted.

Since the rail to Bletchley Park was a bit of a trip, I pulled Professor Steigerwald aside to talk about India. I mentioned what I’d been seeing and asked about the history behind it — he said the drive for resources and manpower was especially prevalent in British India, which was the crown jewel of their empire at that time. The imperial powers were paradoxically dependent upon the colonies while trying to maintain dominance above all else, and India was central to keeping the balance. What he told me to look out for most going forward was the comparative perspective, because he said it was somewhat different in France. Because it’s a republic, there’s something less racist about it and more egalitarian, or at least pseudo-egalitarian. It’s less of the straight superiority complex and overt condescension than you see with the Brits. Here, Professor Davidson joined in — like we discussed in class, Germany didn’t have much colonialism, but what they did have was extremely racist and brutal, especially in Africa with several massacres of indigenous peoples. Those contrasts make sense in conjunction with the jus soli and jus sanguine distinction from Professor Robinson’s Nationalism and Ethnicity course as well. The French at least act like you can be culturally French — they’re extending their civilization so you can be part of it. Britain just thought they’d done so much for the colonies that they deserved loyalty at this point. As the Churchill War Rooms exhibit mentioned, Churchill and the British thought they were the only ones who could provide civilization to India (or at least that’s the justification he gave out loud…).

But when I mentioned that I’ve felt this total lack of remorse for the number of lives they’ve trampled, Professor Steigerwald kind of just agreed. All are fairly unapologetic (and he wants to reconvene to discuss more after the Vel’ d’Hiv museum). Professor Davidson had a fair point that I started to acknowledge near the beginning of this post — I mean, look at the United States. What do we see about the Native Americans at home? Nothing. To be honest, the theme isn’t all that surprising. But because the antiquated sense of royalty is so prevalent in London — be it the centuries-old architecture, fervor about the crown, or the regal palaces and towers at what seems like every street corner — I believe that the concept of empire and the imperialism that enabled it both make London what it is, for better or worse.

On to Bayeux!

Meg

I will add a brief postscript: when I wasn’t busy driving myself insane over this stuff, I did have a blast on this stretch of the trip. I saw Memphis last night and I’m still entranced by the absolutely magnetic Beverley Knight, and the British history from the Magna Carta to Bletchley was truly incredible. I had the best crêpe of my life in Camden Market (although I admittedly may be reevaluating very quickly in France), and exploring the Jamaican district of Brixton with Becca was one of the best times I’ve had in a while.

I ran to some beautiful places:

I wandered aimlessly:

And, naturally, I was touristy:

Long story short, I’m not always as much of a curmudgeon as this post makes me sound, I promise!