Image from here Image from here

Introduction (3,5,7)

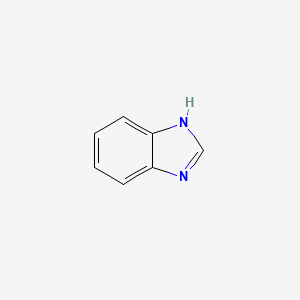

The basic benzimidazole structure has a wide range of biological activities including anticancer, antiviral, antibacterial, antihypertensive, and antioxidant effects. The focus of this page will be to assess the toxicologic effects of benzimidazoles as broad spectrum anthelmintics and fungicides. Examples of anthelmintic benzimidazoles are thiabendazole and mebendazole. These types of products are ingested orally by animals or humans. They selectively kill parasitic worms, but have very little mammalian toxicity in this form. As a fungicide, benzimidazoles are commonly used to control diseases on plants and foods. The most common examples of benzimidazole fungicides include benomyl and carbendazim. The most common toxicity to humans is from exposure to fungicidal benzimidazoles via inhalation, ingestion, or dermal exposure.

Source (6)

Benzimidazole is a heterocyclic aromatic compound made up of a benzene ring fused with imidazole at the 4-5 position. Benzimidazoles are crystalline materials that are insoluble in water. Modifications at various positions on the basic benzimidazole nucleus have led to the development of many active chemicals.

Image from here

Toxicokinetics and Biotransformation (2,7)

When administered orally, benzimidazole anthelmintics are rapidly and extensively metabolized in mammals. Benzimidazoles are generally poorly absorbed and prodrugs have been created to make them more active. Metabolism of these compounds are primarily through normal oxidative and hydrolytic processes and by conjugation. The major enzyme systems responsible for the biotransformation of benzimidazoles are cytochrome P-450 and microsomal flavin monooxygenases. Benzimidazole metabolites predominate in plasma and tissues compared to the parent compound, which is generally short-lived. Excretion occurs in both urine and feces.

Carcinogenicity and Teratogenic Effects(1,4)

Liver tumors were found in mice following chronic exposure. There is limited evidence for risk in humans but benzimidazole’s action on dividing cells is the cause of concern for the promotion of tumorigenesis, teratogenicity, and developmental toxicity. Teratogenic effects have been observed in rats and zebra fish, but epidemiological studies in humans have not confirmed any teratogenicity. This study by Borzsonyi, Pinter, Surjan, and Farkas show how benzimidazoles have both carcinogenic and teratogenic potential.

Mechanism of Action (1,3,5)

Benzimidazoles inhibit fungal growth and kill helminths by inhibiting microtubule assembly. Benzimidazoles bind to the β subunit of tubulin and prevents the addition of more subunits onto the growing microtubule by capping it off.

Image from here

Target Organs (1)

Acute toxicity risk is low, but the skin may be a target if benzimidazole residues are left on the skin for extended periods of time. Chronic studies have resulted in toxic effects in the liver, testes, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal tract.

Signs and Symptoms of Toxicity (7)

There is low toxic risk to mammals following acute exposure. Various toxicology studies have found possible effects of exposure can include:

-Vomiting

-Allergic contact dermatitis following dermal exposure

-Weight loss

-Anemia

-Reduction in liver weights

-Degeneration of testicular tissue

-Transient decrease in leukocyte count

Treatments (4)

There is no antidote for benzimidazoles. Any toxic exposures are treated symptomatically.

If swallowed: Immediately give a glass of water. Do not induce vomiting.

Contact with eyes: Wash eyes with water for at least 15 minutes and seek medical attention if irritation persists

Contact with skin: Immediately remove all contaminated clothing and wash skin with soap and water

If inhaled: Encourage patient to blow their nose to clear nasal passages and seek care if discomfort persists

Genetic Susceptibility or Heritable Traits (2)

There are no heritable or genetic traits in humans affecting toxicity risk of benzimidazoles. Studies have found though that genetic mutations may exist in nematodes that have caused them to become resistant to various benzimidazole derivatives. Genetic mutations in the tubulin molecule and an increase in active cellular efflux of the drugs are thought to be the cause of the resistance.

Historical or Unique Exposures

There have been no major historical exposures of benzimidazoles.

Biomarkers

There are no established biomarkers for benzimidazole exposure, but a potential biomarker could be to measure the levels of benzimidazole metabolites, which are commonly the active compounds.

References

- Costa LG. Toxic Effects of Pesticides. In: Klaassen CD. eds. Casarett and Doull’s Toxicology: The Basic Science of Poisons, Eighth Edition New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013. http://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/content.aspx?bookid=958§ionid=53483747. Accessed May 25, 2020

- Gottschall DW, Theodorides VJ, Wang R. The Metabolism of Benzimidazole Anthelmintics. Parasitology Today. 1990. 6(4): 115-125.

- Lacey E. Mode of Action of Benzimidazoles. Parasitology Today. 1990. 6(4) 112-115.

- Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Benzimidazole Material Safety Data Sheet. Available from: http://datasheets.scbt.com/sc-280611.pdf

- Zhou Y, Xu J, Zhu Y, Duan Y, Zhou M. Mechanism of Action of Benzimidazole Fungicide on Fusarium graminearum: Interfering with Polymerization of Monomeric Tubulin But Not Polymerized Microtubule. Pathophysiology. March 2016. 106(8): 807-813.

- Townsend LB, Wise DS. The Synthesis and Chemistry of Certain Anthelmintic Benzimidazoles. Parasitology Today. 1990. 6(4): 107-112.

- Seiler JP. Toxicology and Genetic Effects of Benzimidazole Compounds. Mutation Research. August 1975. 32: 151-168.