Physiology of the Urinary System

Urine is formed by nephrons present inside the kidneys. The production of urine is the body’s way of eliminating excess water, waste products, and salt. After its formation in the nephrons, the urine flows through several structures in the kidney. From the kidney, the urine flows into the ureters downward into the bladder via peristaltic movement. Contraction of the bladder through micturition (also known as urination), causes the lower end of the ureter to constrict to prevent reflux of the urine upwards. The bladder holds the urine until urination occurs which empties the urine through the urethra. In a female, this lies above the vaginal opening. In a male, the urethra opening lies at the end of the penis. The internal urethral sphincter is at the intersection of the urethra and bladder. The external urethral sphincter is at the base of the urethra and the conscious nervous system directs its control. The bladder and internal urethra sphincter are innervated by the autonomic nervous system. When the bladder contracts and empties urine, the sacral levels (S2-S4) of the spinal cord are at work through the parasympathetic fibers of the autonomic nervous system. When the bladder needs to retain urine, the urethral sphincter is excited by parts of the thoracic and lumbar spinal cord (T11-L2) through sympathetic fibers. An individual sense that the bladder is full by stretch receptors in bladder tissue and sends an impulse to the sacral part of the spinal cord. After the accumulation of roughly 300 mL of urine, the bladder contracts and the internal urethral sphincter muscle relaxes, and an individual feels the need to void (McCance & Huether, 2019).

In normal healthy individuals, there are several mechanisms that attempt to prevent bacteria from invading the bladder or progressing up through the upper urinary tracts. These mechanisms usually work together to prevent infection and they include:

- The process of urinating washes most bacteria out of the urethra

- In females: Mucus secreting cells in the urethra help trap bacteria so it can’t move upward

- In males: the length of the urethra and the prostate and associated glands create secretions to shield bacteria from invading

- Several factors work to create a bactericidal effect: high osmolality and low PH of the urea, uromodulin presence (a protein synthesized in the kidneys), and the epithelial cells of the urinary tract

- When the bladder contracts, the ureterovesical junction (functional one-way valve where the ureters lead into the bladder) closes, thus preventing urine from ascending upwards into the upper urinary tract

- In the distal urethra, the urethral sphincter prevents the upward movement of bacteria

If bacteria were to successfully invade, the immune system recruits toll-like receptors (TLR4) which recognize the pathogen and further recruits neutrophils and macrophages to induce phagocytosis. The ability of the pathogen to produce infection is influenced by the virulence of the specific pathogen and individual’s specific immune response. If the immune system does not respond quick enough, the pathogen may be able to excessively multiply and inundate the individual’s defense mechanism, causing a UTI (McCance & Huether, 2019).

Figure 1. The Urinary System (Charity, 2016)

Types of Urinary Tract Infection:

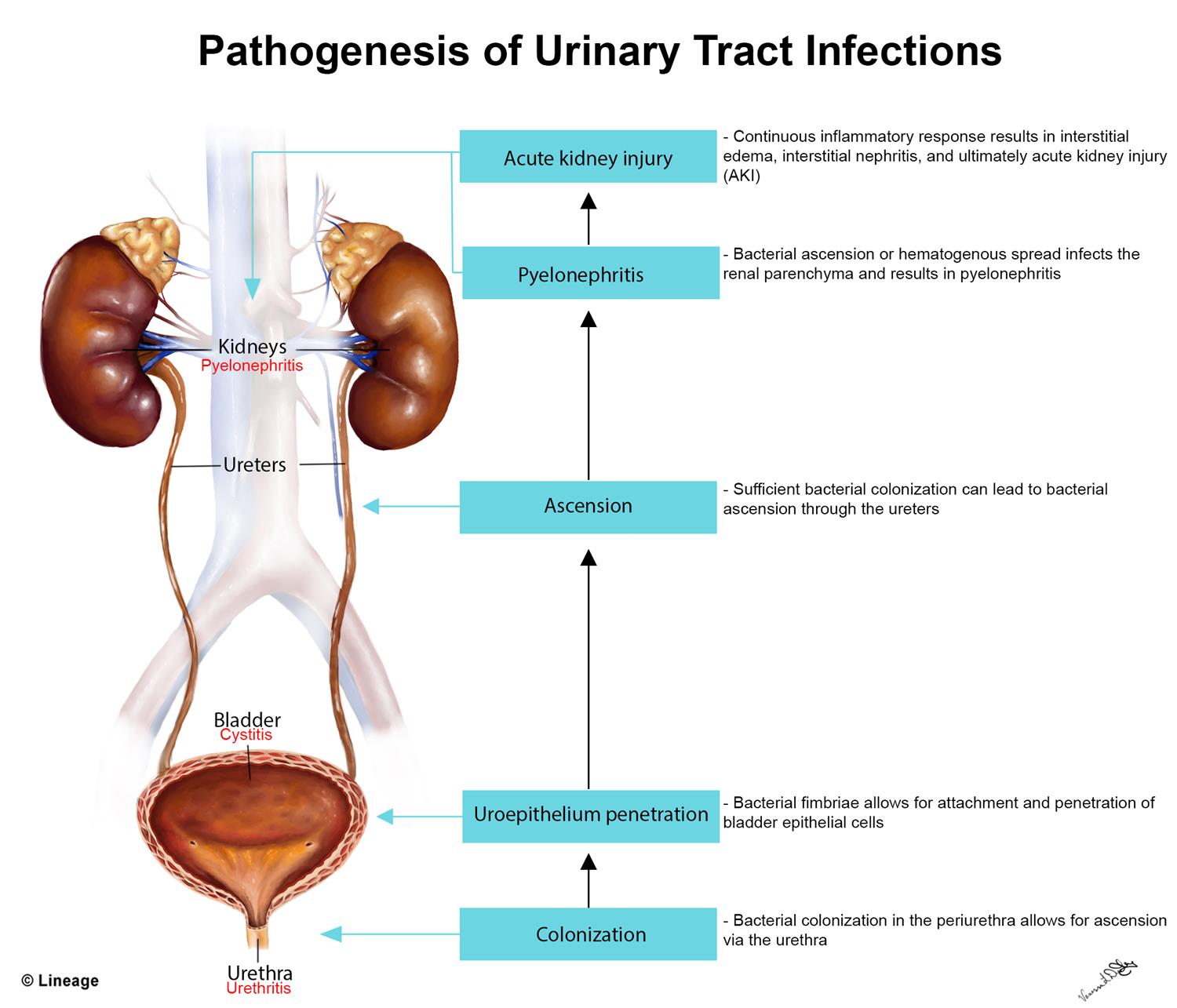

Urinary tract infections are caused by bacterium that invade the urinary epithelium cells causing irritation and inflammation of these cells. The infection can start in the urethra and can progress its way up to the bladder, ureters, or kidney. Infection of the urethra or bladder is known as a lower urinary tract infection while infection of the ureters, renal pelvis or kidney tissue constitutes as a upper urinary tract infection. Women tend to be more prone to urinary tract infections due to their anatomy. Their urethra is shorter than a man’s urethra and thus bacteria can reach the bladder more easily. In addition, a women’s urethral opening is located closer to the anus making it easier for bacteria to migrate from the anus to the uretha.

As mentioned before, there are two main factors which contribute to the development of a UTI:

1.) The ability of the specific pathogen to produce infection

2.) The strength of an individual’s defense mechanisms against the specific pathogen (McCance & Huether, 2019)

Risk Factors: Individuals most at risk for urinary tract infections include women, immunocompromised individuals, prepubescent children, patient’s with urinary catheters, women given antibiotics that may interrupt vaginal flora, individuals with a history of diabetes mellitus, post-menopausal women, sexually active and pregnant women (McCance & Huether, 2019).

Acute Cystitis:

The most common site of a UTI, acute cystitis, is inflammation of the bladder. The urine is contaminated by bacteria that make its way up to the bladder. Most commonly a UTI occurs through the reversed movement of bacteria or pathogens (most commonly Escherichia coli) from the gut (where it usually resides) up to the urethra then to the bladder (McCance & Huether, 2019). The migration of this particular bacteria from the perianal area to the urethra opening may be due to poor wiping after a bowel movement, sexual intercourse or holding urine as urinating helps flush the bacteria from the body. Escherichia coli has several mechanisms that makes it more virulent and resistant to the immune system. They produce toxins called cytotoxin necrotizing factor-1 and hemolysis and they are resistant to complement. Other bacteria that can cause UTIs work together to create a biofilm that helps with efficient reproduction and resists the defense mechanisms of the host as well as the antibiotic treatment that may be prescribed. The E.coli bacterium have particular structural features such as type-1 fimbriae that attach to the uroepithelial cells and their flagella help to push them upstream. In some women, genetics make them more prone to infection by some strains of E.coli. Other pathogens that may contribute to infection include Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Pseudomonas, Proteus, and Klebsiella. Fungi such as Candida, viruses, and parasites such as Schistosoma haematobium are also common infection sources. The cystitis, or inflammation of the bladder, can cause the epithelial cells of the bladder to appear red, pus-like or exudate in appearance as made visible by a cystoscopy, a procedure where the insertion of a flexible tube is used to view the structures of the bladder (McCance & Huether, 2019)

The inflammation of the bladder causes the common UTI symptoms of low back pain, urgency, frequency, and painful urination, also known as dysuria. The inflammation also causes the stretch receptors on the surface of the bladder to cause an individual to feel like they have a full bladder even when they only urinate a small amount. Other symptoms include flank pain, hematuria (blood in urine), and cloudy urine. Older adults with UTIs may demonstrate confusion and may be asymptomatic with regards to urinary symptoms (McCance & Huether, 2019).

Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome

Interstitial Cystitis (IC) or also known as Painful Bladder Syndrome (PBS) creates a chronic pain related to the lower urinary tract, more specifically, the bladder. Individuals with this experience a pain or pressure sensation symptom for greater than 6 weeks but no infection can be identified. While the cause of interstitial cystitis is not known, an autoimmune response triggers inflammation that increase the sensitivity of neurons in the mucosa of the bladder, making it more vulnerable to bacteria colonization. The inflammation and hardening of the wall of the bladder can also create hemorrhagic ulcers and a decrease in bladder capacity. The epithelial cells of the bladder also secrete antiproliferative factor (AFP) which block cell growth of the inner wall of the bladder and causes an increased bladder sensation (McCance & Huether, 2019)

Acute Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis is an infection of one or both upper urinary tracts. Acute pyelonephritis is usually associated with the microorganisms E. coli, Proteus, and Pseudomonas. Urinary obstruction and reflux of urine from the bladder are the most common risk factors, along with being a female. These certain microorganisms make the urine more alkaline by splitting urea into ammonia, and this increases the risk of stone formation. The infection is possibly spread along the ureters or via the bloodstream. This triggers the inflammatory process and can cause unnecessary fluid build up, inflammation or purulent urine. Both of the kidneys are usually involved as well as the renal tubules, but this rarely causes renal failure. Healing occurs with deposition of scar tissue, fibrosis, and atrophy of affected tubules after the acute phase. These individuals experience the same symptoms as those with acute cystitis in addition to fever, chills, flank pain and costovertebral tenderness (McCance & Huether, 2019).

Chronic Pyelonephritis

Chronic pyelonephritis is recurrent infection of the kidney which leads to scarring. Various causes are idiopathic, chronic UTI’s, renal stones, or recurrent episodes of acute pyelonephritis. Chronic UTI’s prevent the elimination of bacteria and triggers the inflammatory process which leads to destruction or atrophy of the tubules, significant scarring and impaired urine concentrating ability. These all ultimately lead to chronic kidney failure (McCance & Huether, 2019).

Figure 2. Pathogenesis of Urinary Tract Infection (Dominguez, 2019)

Classifications of Urinary Tract Infections:

Uncomplicated UTI: mild UTI, without complications, occur in normal urinary tracts

Complicated (febrile): abnormality in urinary system or individual has a health problem that compromises host’s defenses (HIV, diabetes, kidney stones, pyelonephritis, renal transplant)

Recurrent UTI: three or more UTIs in 12 months or 2 or more occurrences within 6 month

-Relapse: a second UTI caused by the same pathogen within 2 weeks of first treatment

-Reinfection: a UTI that occurs greater than 2 weeks after completing treatment for same or a different pathogen

(McCance & Huether, 2019)

Diagnosis and Treatment

In acute cystitis, diagnosis is made through a clinical assessment, identification of patient-specific risk factors, and observation of patient symptoms. In addition, a urinalysis is obtained to view the appearance and concentration of the urine specimen. A urine culture will be performed to identify the specific pathogen present. An antibiotic designed to treat the specific microorganism present will be prescribed. If an individual presents with more systemic symptoms such as fevers, chills, or flank pain, pyelonephritis should be suspected. A urine culture and urinalysis will also be completed. White blood cell casts present in the urine indicate pyelonephritis but they’re not always present in the urine. Antibiotic treatment for the specific pathogen is prescribed. In individuals with complicated pyelonephritis, blood cultures and urinary tract imaging may be necessary. For recurrent urinary tract infections, ultrasound or cytoscopy imaging may be indicated to get a better visual picture of the urinary tract system (McCance & Huether, 2019).