Postcolonial Shakespearean Lineages in England

Keywords: Theatre, Theatre Education, Diaspora, Ira Aldridge, Red Velvet, Othello, Decolonization, Diversity, Djanet Sears, Toni Morrison, Representation.

Interview audio

Published on 26 September 2023.

Lolita Chakrabarti

Interview transcript

Introduction

Amrita Dhar

Hello and welcome. My name is Amrita Dhar, and I am the Director of the project Shakespeare in the “Post”Colonies which is hosting a series of interviews with postcolonial Shakespeareans from around the world.

In today’s conversation, I talk to the British playwright, actress, dramaturge, and producer–and close to my heart, also a member of the Bengali diaspora–Lolita Chakrabarti.

Conversation

Amrita Dhar

Hello—Welcome very much, Lolita Chakrabarti. You have been, and you are, a South-Asian-descent theatre practitioner in the twentieth- and twenty-first-century UK. Now, what is that like in a world that wants to claim that it inhabits post-colonial days, times after the end of empire? Especially after the formal withdrawal of the UK from many of its political colonies across the world?

Lolita Chakrabarti

What is it like? Well, post-colonial. How can you ever see yourself, really? You’re in the context of, you’re where you are, so you don’t have any retrospective view on that, right? I mean, I am post-colonial, I’m definitely part of colonial history, aren’t I? Because I’m in Britain, because my parents came here, and they were invited here, to work, and they came and set up. So, I wouldn’t be here without it.

Amrita Dhar

What is it like being a South-Asian-descent theatre practitioner today?

Lolita Chakrabarti

I graduated from drama school in 1990. And it’s easier now than it was then. Then, it was a brave new world of… I didn’t see very many people like me around, and so, you kind of think, “Well, where do I fit?” And I had quite an idealistic viewpoint, where I was, like, “Right, I’m going to make my space. Let me cut my path, and I’m going to fit because I’m, I’m here, and I’m new, and this is what I want to do.” But now, there are many more faces like me on TV and theatre and film, which is amazing. It’s an amazing thing to see, actually, that in your lifetime… And thank God! Because it felt so backwards thirty-two years ago. So, I feel like the world is just catching up with what I want…

Amrita Dhar

Do you see people of your generation? I mean, or do you see younger people, newer people?

Lolita Chakrabarti

Younger, younger, yeah. I mean, there are a few people of my generation that I’ve known, I’ve spotted or met, or…but there’s not many of us, no. It’s definitely younger. I think if I had come out of drama school ten years ago, it would be a very exciting time. You know, given if you have the opportunities and all of those other things that go with making a successful career. But it’s a really exciting time in terms of how many people are out there.

Amrita Dhar

Does it feel as though in the UK… I mean, the UK fudges, isn’t it? I mean, it’s almost like “Well, we never had slavery,” so there’s a convenient fiction…

Lolita Chakrabarti

[laughs]

Amrita Dhar

…for instance, that the UK just… It’s always fudging, fudging its history, fudging in the contemporary… So, is the rhetoric in the UK about how it genuinely is post-colonial, or does it admit that it is colonial? Or does it elide the whole conversation?

Lolita Chakrabarti

Gosh, that’s a complicated question. I think in the last couple of years, it has had to look at its colonial history, and it is starting to acknowledge it, but literally starting. So, we had a statue of, don’t know his first name, but I think it was Edward Colston. I’m not sure. But he was a slaver in Bristol, and this statue got pulled down. And it caused a huge, you know, as it could in England, only in England… Well, this whole conversation is: statues, and what are we commemorating? And why? Because these statues just live amongst us elevating things that shouldn’t be elevated now, right? So, it caused a huge ruckus and discussion. And that was just one of the elements that people are starting to question: What is our history? How do we present it? Where do people like you and I fit in? Because, yes, that’s a good word, “fudge.” It is a sort of blurred, undistinguishable line of “Well you weren’t really here,” you know, this sort of selective memory or kind of amnesia, or I don’t know what it is, but it doesn’t answer the question straight. So yes, that has definitely been part of the story. And then you get people… I mean, the whole point about artists is that we go, “Well, here we are, this is our story, we’re going to tell it.” But you need avenues in which to be helped to tell it. So, I guess as an artist, the avenues are getting more.

Amrita Dhar

You’ve been part of creating some of these avenues, I have to say.

Lolita Chakrabarti

Yeah. Yeah.

Amrita Dhar

And we’ll talk about that in a sec…. Can you say a little bit about your… Again, this is almost a personal question, but about the South Asian/Bengali diaspora experience, and where, or, if at all, Shakespeare fits into that experience, through a kind of postcolonial inheritance? And this could be, we could be talking about this as sort of through your parents, for example, or extended family, or close friends. Even if you haven’t sort of inhabited post-colonial geographies for extended periods of time, how has a postcolonial inheritance informed your relationship with Shakespeare?

Lolita Chakrabarti

So, my parents came to Britain in 1960. Obviously, they grew up as young children in the Raj, and they were part of the Independence. So, they came in 1960, when they were in their 20s. But they were children at that time, so it’s a different kind of experience, right? They weren’t adults fighting the fight. They had been children when that happened. And in 1960, they came over because Britain invited immigrant communities in the Commonwealth to come and help, uh, you know, workforces. So, my dad’s a doctor, my mum’s a housewife, and they came, and my dad has been an NHS [National Health Service] man ever since. So, I guess, that, as a postcolonial journey, informs everything that I am, because I’ve been brought up… I was born in Britain. I’ve grown up and I work in Britain. Or I work anywhere that will have me, but you know, this is my base. I spent a very crucial eighteen months in Kolkata when I was ten—because my parents tried to emigrate back a few times, and it didn’t quite work out. But that was very influential in terms of me understanding what I am and who I am, and, just, you know, really basic things like taste. [laughs] I have a taste for Indian food! And just having the culture inside me because of that experience when I was a child.

But I would say that looking at my parents, understanding where they’re from, and being here and being of England is everything that I am. So, all my work is completely about—what is it about?—it’s about being outside looking in. But then that could also be because I’m a woman, and I know we make up more than half of the population [laughs], but we’re still often on the outside looking in. So, I’m not sure which of my elements is making up the story. But definitely the culture that I’m from, and that idea of immigrant mentality, as well… But it baffles, not baffles me, amazes me that when people leave their country and start fresh in another place completely and make it work. How extraordinary! I mean, what pioneering spirit is that? And, you know, you take your parents for granted, don’t you? You think “Oh, they’re just my Mum and Dad, and they’re annoying.” But when you think of that kind of pioneering spirit, you just go, “I don’t know if I would have that in me.” So, and I think all of those… They have that, and I must carry that in some way. Maybe that’s the pioneering spirit I take into my work. I don’t have to change country, but I use that in my work.

Amrita Dhar

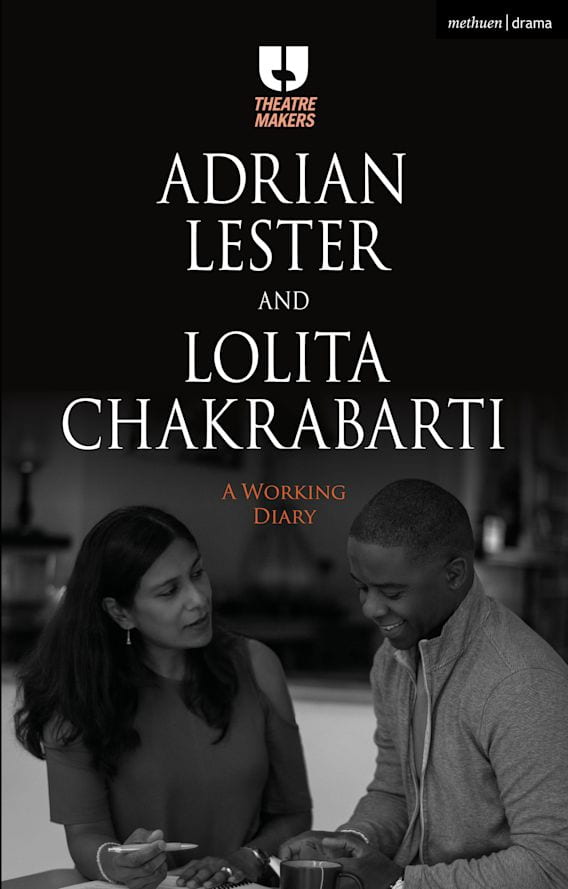

Looking at this Working Diary that you co-edited with your husband, Adrian Lester, there is some of that, surely, that translates into also just life as you live it. Because, I mean, it’s not as though you’re married to a Bengali…

Lolita Chakrabarti

No.

Amrita Dhar

It’s not as though your children are exactly Bengali…

Lolita Chakrabarti

No.

Amrita Dhar

And in the Working Diary, that publication really foregrounds so much postcolonial energy, for lack of a better word. Would you be willing to talk a little bit about just how you see that energy playing out in your life, including your professional life?

A Working Diary by Adrian Lester and Lolita Chakrabarti (Bloomsbury, 2020).

Lolita Chakrabarti

That’s interesting that you phrase it like that. I think it’s a driving force, absolutely a driving force. The arts are where we see ourselves, right? We, we have a shared experience that we all understand. And from an early age, I absolutely had those shared experiences in theatres and on television, and I was, you know, enamored of, “Gosh, this is amazing, these stories happen, and I can experience all these different lives.” But I also didn’t necessarily see myself in those stories, or my kind of, my history—I mean, all of our histories are very particular, right, so, you can’t see all of our histories, that would just be too much—but some element of my history that made me think, “Oh, that’s me,” as well, more specifically me. And so, a driving force has been to tell my story. Yeah, completely tell my story. From my parents, from that immigrant mentality, that… You know, I see young people here now, who are from other countries, who are on the bottom rung, working their socks off in order to do something else. It’s an imbedded thing, that, that you can’t understand if you’re a native of a country. I don’t think you can understand it. It is “I will do absolutely anything because the opportunity here is better than what I left behind, and I’m going to make it work.” It is a bloody-minded, uncompromising, unvictimized—you’re not a victim, you are absolutely, “This is what I’ve been given, it’s an opportunity, and I am going to work it to help me.” It’s a survival thing.

And so, I think that energy from my parents has absolutely informed how I approach the industry. And also, when the industry is not particularly… I mean, it’s changed. A, I’m older, and I’ve had more successes, so the doors are open more. Nothing breeds door opening more than success, you know. But I’ve had a lot of years where the doors have slammed totally shut. The walls are very solid, and you can’t climb over them, either. [laughs] So, you’re just sort of standing there going, “How do I move?” And, I don’t know, you just keep pushing for what you think is, is important. Doesn’t mean you’ll get anywhere necessarily… but I guess my dad always said, “A sincere heart will come through.” And I like that. I don’t know. You know, I like that. So, I’ve kept pushing.

Amrita Dhar

Right, right, yes. Well, talking about pushing, talking about tenacity, talking about drive. Let’s talk about Ira Aldridge. You’ve written this beautiful play, which I teach, which I love, which I love talking about, called Red Velvet, which tells something of the story of a remarkable Shakespearean actor called Ira Aldridge. Could you perhaps talk a little bit about what you think Shakespeare meant for Ira Aldridge? I mean, was Shakespeare a kind of colonial presence? Was Shakespeare a “civilizing” force that he had to reckon with? An imposition? As indeed Shakespeare was in so many parts of the world, including my own. I grew up in Calcutta, and that’s how Shakespeare came to be. I mean, that’s not exactly my relationship with Shakespeare, but I know that that is how Shakespeare came to be in a place where I got to encounter him.

Playbill from Theatre Royal’s 1833 Othello, starring Ira Aldridge; image from LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection

Lolita Chakrabarti

Mm.

Amrita Dhar

He didn’t come to my shores benignly.

Lolita Chakrabarti

Mm.

Amrita Dhar

I mean, was Shakespeare a way in for Ira Aldridge where he wasn’t otherwise welcome? What do you think Shakespeare was for Aldridge?

Lolita Chakrabarti

So, the Ira Aldridge in my play is, is my interpretation of who I think he was. And I have combined the historical facts of his life and his journey with my knowledge of what it is to be a person of colour in the theatre. And admittedly, there’s a hundred and fifty years between us! [laughs] So, mine is a more modified version. But I have tried to interpret that through a Victorian lens. I think, from my point of view, studying Shakespeare and playing Shakespeare are very different, different things. And when we… So, I was in a production of Hamlet, and I was asked before I was in rehearsals—so I didn’t know the play very well, I’d read it a few times, but I hadn’t sort of gone through the rehearsal process—to write a piece for the program, because obviously, this has to be worked out early. And because I’m a writer, they said, “Would you write something?” And I, I said, yes, and then I felt completely terrified, because I thought, Hamlet is the play in the world, right? It is the play everybody knows, everyone can probably quote “To be, or not to be” a little bit, you know, everybody has some reference to that story. And I thought, who am I to write anything? Well, I don’t know anything about anything. And I read a few academic essays and things like that, and I’m not that academically minded, so I got a bit lost in the theory. And then I read the play. I went back to the play. And I was playing Gertrude. And I looked at it, and I thought, as a performer, you respond to Shakespeare in a totally visceral, emotional way. And if you’re studying it, it’s a very different thing. So, the piece I wrote in the program was my response, as an actor, to being in Hamlet.

Red Velvet by Lolita Chakrabarti (Bloomsbury, 2012)

And for, for Ira Aldridge, I… This is my interpretation of what I think he would have been. But I don’t think he would have been a “civilizing” thing. I mean, the thing about Shakespeare, it’s a bit like opera to me. I don’t necessarily get opera. And I used to think, “Oh, it’s because I’m not clever enough to understand it. I haven’t got the key to unlock it.” But I think it’s a taste thing. And if you see Shakespeare, and you respond to it, it’s yours, because it’s a universal thing. I mean, yes, there are complexities within things like Merchant of Venice and, and Othello now. There are racial complexities that, you know, are quite difficult to just go, “Okay, I feel this play, it’s marvelous.” But something like Hamlet that is a universal story about universal emotions and feelings at a scale that hopefully none of us really live out. You can get involved in it and, and find moments of truth that relate to who you are now. So, I don’t think it was a civilizing thing. No, I think it’s like hearing a piece of music, and if you hear it played well, there is nothing like it. And it is the height of acting. If you can play Shakespeare well, it is the pinnacle of your art.

Amrita Dhar

Do you think it opened doors? I mean, of course, it opened doors for Ira Aldridge. But could there have been ways in which Shakespeare limited him?

Lolita Chakrabarti

I studied Othello for my O Levels, which is like the exams you do at sixteen. So, I knew it relatively well from school. And I loved it as a play. You know, I’d studied all the soliloquies. And I thought… the language and all the things I’d been taught. And so, when I wrote Red Velvet, I absolutely wrote from a place of love of Othello. And then weirdly, in between our first production of Red Velvet in 2012, and when it returned in 2014, in 2013, my other half, Adrian Lester played Othello at the National Theatre. And, of course, I went to see it. And I found it a very difficult experience. I came out… He was brilliant. The production was brilliant, you know. Rory Kinnear played Iago. There was a fabulous cast. It was beautifully done. But I found it such a distasteful play. And I thought, I don’t want to see that again. So, my relationship with Othello has changed a lot. And I thought if, in Act Three, Scene Three, there was a bit more… [laughs] If I understood why he changed his mind, if it had been opened up for me so that the logic of it made me travel the rest of the story, I would be fine. But actually, Othello just changes. Iago manipulates him, and he changes, and then he turns against every… his wife, and he heads towards tragedy. And I, now I find that very difficult to stomach. But you know, I mean, this is still regarded as one of the greatest plays, a pinnacle of somebody’s career.

So, in Ira Aldridge’s time, it must have worked, right? Our sensibilities are different now, and my sensibilities are mine. So hard to answer that, would he have been compromised through Shakespeare?

I mean, I think he was released through playing things like King Lear and Macbeth, you know, because he did white up to play these roles, and there were, I love this description of, you know, when Edmund Kean played Othello he obviously blacked up, but you can’t put the black makeup on your hands because when you’re handling Desdemona, the black makeup will come off on her white dress. So, he would black up his face, and he would wear gloves. So that you just thought, “Okay, he is playing a Black person.” But Ira, when he played his white roles in Shakespeare, when he played King Lear, would white up his face, would wear one glove, and have one glove in his hand, so that you could see that he was Black. It’s so interesting, because at the end of Red Velvet, so many people were upset, they thought, “Oh, my God, he had to compromise his art.” And he had to white up in order to be accepted. But to me, it was a defiant thing that he whited up. He said, “If you need to accept me in this role, and to play the father of these three, obviously white actresses, that’s fine. I can transform. But know that it is a clever transformation. Because look at me, I’m a Black person.”

Amrita Dhar

That’s fascinating. That’s kind of wonderful, also.

Lolita Chakrabarti

People would weep at the end of the play, and I after a while, I thought, well, that’s fine. That’s your experience and your interpretation, but I don’t see it as a devastating moment.

Amrita Dhar

Right, right. There is a lot of discussion these days about decolonization, you know, at the level of theatre, at the level of curriculum. And, I mean, I am an academic in the US, and it’s a very trendy thing for university administrators to say that they’re “decolonizing the curriculum” and so on. What is it like in the UK? I mean, I think this relates to, I mean, I think we thankfully agree that it is not a good idea for Anthony Hopkins to be in blackface and play Othello. It’s simply, just, you know, not a good idea anymore.

Lolita Chakrabarti

Mm.

Amrita Dhar

And I think we’re at a point where we would even say, let’s not have Adrian Lester, for instance, white up to play Macbeth.

Lolita Chakrabarti

Mm.

Amrita Dhar

Indeed, you know, Denzel Washington’s Macbeth that has just come out. It is a problem that there are so few Black or brown Macbeths, Lears, and so on, especially in the UK-US axis. What is it like in the UK? Do you have any thoughts on how something like Shakespeare can be made to do the ongoing work of decolonization?

Lolita Chakrabarti

Decolonizing is definitely here. I don’t know if it’s in school… Well, it is. One of my kids is still at school, so they are talking about it. I don’t know to what degree. But drama schools definitely across Britain are all talking about decolonizing and reframing. To me, I think, well, that’s just having a wider point of view, isn’t it? That’s including works from people that are luminary in other parts of the world, and are excellent pieces of classical and modern texts, and having different kinds of people coming in and realizing it, interpreting it. So, everyone behind the scenes needs to be of all kinds of diversity as well. So, that’s what decolonizing the curriculum seems to me, and they’re all sort of obviously having to define it, because they have to write these policies.

Amrita Dhar

How real is it?—is, I guess, my question. It’s not particularly real, unfortunately, you know, no matter how much these US universities might talk about decolonization, it’s always, over here, a question of trying to retrofit into ultimately a very exclusive institutional setup.

Lolita Chakrabarti

Mm. Mm. I can’t speak for universities, because I think that’s a different type of institution. But in drama schools, it’s definitely been thrown in the air, and it’s being acted upon. And maybe that is the precursor to anything happening in a university, perhaps? Because, actually, who you see on your screen, and the stories that are told in the theatre, obviously, will influence… obviously, we are influenced as creatives by what’s going on in the world. But then also the world is influenced by what we produce. And I think there has been, oh my God, in the last three years, I have noticed an explosion of opportunities for people like me. I’m suddenly very desirable. [laughs] You know, it has changed.

Amrita Dhar

After thirty years in the profession.

Lolita Chakrabarti

Yeah, absolutely. It has changed. I am fashionable. Who would ever have thought that? You know, I might be a bit old, I might be falling off on that one now, that bit. I’m a bit old for it. But I’m definitely fashionable for my skin colour. But I think there is change, yes, on the ground, absolutely happening. And I think that people like me, those of us in the profession who are older, are, are pushing for it more. And my colleagues who are white are also pushing for it. Because everybody has… We’ve all sat at home, right, during covid? We’ve all been locked away in our own little worlds watching screens, watching the terrible news evolve, and going, “How can these terrible things be happening, and we not do anything?” So, I think yes, there is a mixture of the complacency that you’re talking about in certain institutions, and the need to shift it in the industry. But we have to see, right? I thought, well, I’ve thought all along, it’s interesting that the people who are now opening doors to me are also the ones who closed the doors five years ago. And memory is short. And you know, am I going to say, “Well, you shut the door to me five years ago,” or am I going to walk through the door and go, “Okay, let me take this opportunity”? It’s a complicated, I feel like I’m standing on the fault line of something that is hopefully going to change.

Amrita Dhar

That’s really interesting. Something about what you’re describing sounds just practical and smart to me. Because probably, hopefully, the industry of theatre and entertainment in the UK realizes that this is something that absolutely needs to happen for its survival.

Lolita Chakrabarti

Yes.

Amrita Dhar

And that might be… I’m always wary of attributing great saintly intentionality where the historical track record indicates otherwise. So, maybe it’s just that matter of what we need to do to survive.

Lolita Chakrabarti

Yes. I think there is an embarrassment at how it has got this far in the industry. And I think you’re absolutely right, you risk your relevance. So, I see things now, that…you know, a TV program or a film five, ten years ago, and I mean, on the female front, you know, with the #MeToo movement, and all of these things that’s been happening, you just go, “Oh my goodness, that is five years old, and look how the women are portrayed.” And we were alright with it! I think the world has shifted so exponentially. You can’t make that programme anymore. You just can’t. So, there are certain elements that have gone. And I think this flurry of “Right, we need other people in… Other types of people involved,” will hopefully gather moss. Because it’s very clear that when you get a different perspective in charge, they will bring in a different workforce. They’ll obviously use the people that are there, but they’ll bring a different flavour. Makes it really interesting. Everybody goes, “Oh, I don’t know that flavour,” and it becomes something to follow. So, I think that when financial success follows the sort of shifts that have happened, we’re on our way. I do think we’re on our way, and just maybe academia will take a little longer.

Amrita Dhar

To kind of return to Red Velvet and also to think capaciously as we just have been: my graduate students always point out that Red Velvet is ultimately quite a political piece of writing, and they enormously value it for that reason. That here is a piece of theatre that, like Djanet Sears’s Harlem Duet, for example, or Toni Morrison’s Desdemona, thinks clearly and speaks its mind. Not in a kind of, you know, not wagging a finger at you, it is real art, but it does think clearly and speak its mind. Can I ask you to talk a little bit about how political you wanted it to be, and where you see the position of ideology with respect to art of any kind, especially your art?

Harlem Duet by Djanet Sears (Scirocco Drama, 1997)

Desdemona by Toni Morrison and Rokia Traoré (Oberon Books, 2012)

Lolita Chakrabarti

There’s so many elements in Red Velvet. I poured every thought I had about performance and perception, and how we are seen, how we like to be seen, how we project ourselves, and who we genuinely are, into this play. I mean, it’s all sort of pushed in there. You know, how your politics can be one thing in your mouth, but another thing in your actions, that kind of thing.

John Kani, a South African actor, writer, director, he’s just extraordinary. He was interviewed on television, and he talked about performing Macbeth, I think it was in Johannesburg during Apartheid. And he played Macbeth. And there was a white actress playing Lady M. And he said, this was at a time when, you know, Black and white were not meant to be on stage together. And every night there was some seats that, you know, people would leave, because they were just appalled that this was happening on stage. And he was a very persuasive and a charming talker on this chat show. And he said, “But that’s the point of theatre, right? It’s to be political and to challenge.” And having sat through so much theatre that doesn’t do that at all, you know, so much theatre that is lauded by the certain demographic of person writing the reviews, certain demographic in the audience, certain demographic on the stage, who is the writer, you know, they’re all agreeing, “Isn’t this a marvellous piece of work?” And then I would go and watch it and go “It’s boring. I don’t understand why… This says nothing to me.” And I loved that idea that Shakespeare was political. And so, John Kani, who I’ve never met, sadly, but who on this TV program, placed it in a context I understood. Because I grew up in the 80s. And Apartheid, you know, the sanctions were in place, and we were we were politically active against, you know, don’t buy this, let’s not support South Africa in any way. It totally made sense to me when he painted it in that way.

So, there’s a bit of Othello in Red Velvet. And I wanted to re-politicize that bit of Shakespeare. Because when I’ve seen productions of Othello, before the one that Adrian did, but when I’ve seen other productions, I’ve noticed that—of course, we’ve all changed, right everybody has a good level of conversation about race, and prejudice, and we can all have these conversations no matter what colour or size or shape we are—and often, when I’ve seen Othello, the actors who are having to be racist on stage find it very difficult, because they don’t want to play that. And I totally understand it’s a horrible thing. And they don’t want to play that, and they don’t want to reveal, if they do play that, where it goes. Or what it might reveal in them. I mean, I can understand the anxiety of it. So often, that element of the play is fudged. And you kind of go, “Oh, okay, did they, did they not like him just bec… I don’t know why they don’t like him.” And it’s not really played. And I wanted to reinstate this idea. You’ve got Black Othello, white Desdemona, what did it mean in that environment then? And I did it by having Black Ira Aldridge, white Ellen Tree, and the majority-white audience that we are imagining watching it. So that’s one element of the political nature of the play. This sort of reframing that we’re doing now, this decolonizing that we’re doing now, as a culture, I was doing that within the play and saying, “Lets look at this through my eyes.”

Adrian always said to me, “You make us look with a Brown eye.” And I didn’t really understand what that meant. I was like, “Okay, fine.” [laughs] But I get it now. Because it’s exactly that. Look through my eyes, as a Brown eye, but a female eye, also. Somebody who is really used to being on the outside most of the time. And take a look at the world as I see it.

Amrita Dhar

Yes, and it does. That’s so right. I mean, it does look absurd, doesn’t it? Once you start realizing, “Oh, that’s their objection?”

Lolita Chakrabarti

Yeah. [laughs]

Amrita Dhar

“Too Black to be the Black person that is Othello!”

Lolita Chakrabarti

Yes, yes…

Amrita Dhar

Go on…

Lolita Chakrabarti

Well, I was just going to say, the question being that “Can you play the higher parts of Othello when you’re a base Black person?” And you’re going, “But this character is a Black person.” And it reveals more about the other characters. Because that’s obviously what is always revealed, right? When you make judgments on other people, you reveal much more about yourself than the person you’re talking about.

Amrita Dhar

Quite. Thank you. Thank you so much. It has been just such a delight talking to you.

Lolita Chakrabarti

Oh, thank you, Amrita, you, too.

Amrita Dhar

Thank you so much.

Poster for Hamnet, produced by The Royal Shakespeare Company and Neal Street Productions, and adapted by Lolita Chakrabarti (Garrick Theatre, 2023)

Conclusion

Amrita Dhar

If you enjoyed this conversation, please subscribe to this podcast, spread the word and leave a review. Do take a look also at our project website at shakespearepostcolonies.osu.edu for materials supplementing this conversation and for further project details. Thank you for listening, and until next time, for the Shakespeare in the “Post”Colonies Project, I am Amrita Dhar.