The Ohio State University Center for Historical Research

2023-2025 Series

With the rise of political protests and populist movements, it has become a journalistic commonplace to argue that we live in an “age of anger.” For historians, this widespread use of “anger” as an explanation for most social movements, from populist protests to human rights or social rights mobilizations, raises many questions. First, this approach postulates that people are acting in “anger” when other motivations, such as “despair” or “disenchantment,” could also be invoked. Second, “anger” is presented as a coherent emotional concept, that works as a powerful drive across human history, with ups and downs coinciding with moments of tensions, political protests, rebellions, or revolutions. Third, “anger” is framed as a universal experience shared across all emotional cultures. All these interpretations universalize and essentialize a category which is, by definition, a cultural construction.

Evidence of the instability of the concept of “anger” can be found in all social sciences. In the late 1960s, anthropologist Jean L. Briggs showed that certain people such as the Utku, a small group of Inuit living in the Canadian Northwest territories, have no equivalent concept of anger. Studies in historical linguistics also undermine the assumption that anger is a single transhistorical emotion. In his 1941 essay on affective life, French historian Lucien Febvre famously argued that each human group in the past had its own mental attitudes and categories, calling therefore for a “history of emotional life of man in all its manifestations”. This proposal for CHR programming for 2023-25 responds to that challenge, offering a series of lectures, workshops and public events that explore anger or rage in all their nuances from Ancient Greece to the present.

Defined by Aristotle as unifying pain and pleasure as well as emotional agitation and complex judgment, should anger be considered a valuable function for defending order or a group’s social position, or denounced as a capital sin (Gregory the Great) and, more recently, a self-destructive force? How does anger, individual and/or collective, contribute to the dynamics of violence in contexts as diverse as riots or revolutions, civil wars, or wars of religions, acts of terrorism or massacres? How does the struggle for emotional control impact the history of ideas, the history of science and medicine, gender history, or the history of family, and what does a more global history of anger, not exclusively focused on the Western world, add to our understanding of the complexity of an emotion, both public and private, political, social, and religious?

SPRING 2025 PROGRAM

All CHR events are free and open to the public. Find out about Visitor Parking at Ohio State University:

https://osu.campusparc.com/find-parking/academic-visitor-parking/

Tues., Feb. 25, 2025 – 4:00 to 5:30 p.m.:

“Do you have to be angry to slaughter? Reflections on the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre (France, 1572),” Jérémie Foa, Associate Professor of Modern History, Aix-Marseille University

Location: Colloquia (3rd floor) at the 18th Ave. Library REGISTRATION

![]() This talk will explore the mechanisms by which the principal killers of the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre achieved their ends. The question of the killers’ ideological motivations has often been raised, in particular to highlight the religious anxieties at the core of their behavior. However, other emotions should also be addressed, such as anger, desire for revenge and frustration. After investigating the role of these emotions in the process of violence, this talk will examine whether anger is sufficient to kill, and what the prerequisites are for a guilt-free massacre.

This talk will explore the mechanisms by which the principal killers of the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre achieved their ends. The question of the killers’ ideological motivations has often been raised, in particular to highlight the religious anxieties at the core of their behavior. However, other emotions should also be addressed, such as anger, desire for revenge and frustration. After investigating the role of these emotions in the process of violence, this talk will examine whether anger is sufficient to kill, and what the prerequisites are for a guilt-free massacre.

A former student at the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Fontenay-Saint-Cloud, Jérémie Foa is a Associate Professor at Aix-Marseille University, a member of the TELEMMe laboratory, and an honorary member of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton and the Institut Universitaire de France. A specialist in the Wars of Religion and mass violence in the 16th century, he recently published Tous ceux qui tombent. Visages du massacre de la Saint-Barthélemy, Paris, La Découverte 2021, in which he proposes a micro-history of the massacre, an investigation “from below” of both the victims and the ordinary murderers of the summer of 1572, in Paris and in the provinces. Next book : Survivre. Une histoire des guerres de Religion, to be pushed, Seuil, 2024. He is currently working on a project, in collaboration with Diane Roussel, on the siege of Paris (May-August 1590), which resulted in tens of thousands of deaths.

Tues., Mar. 18, 2025 – 4:00 to 5:30:

“What is Honor?,” Douglas Cairns, Professor of Classics, the University of Edinburgh

Location: Colloquia (3rd floor) at the 18th Ave. Library REGISTRATION

![]() Honor is a topic on which a great deal has been written, but it remains very poorly understood. A typical failing is to ghettoize the phenomenon – as limited only to some forms of interaction (found in some contexts and not in others), as a concern only of one social stratum among many, as a male-gendered phenomenon, as a characteristic only of certain forms of social organisation. This can extend even to the claim that there are ‘honour societies’ that differ fundamentally from ‘dignity societies’ (echoing the older and now widely discredited antithesis between ‘shame cultures’ and ‘guilt cultures’). Such antitheses entail a distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic values that is useful for analysing individual tendencies and historical and cultural differences. But there is no group and no historical society (and perhaps, except in extreme pathological cases, no individual either) in which some combination of both tendencies is not found. Despite strong reasons for believing that contemporary Western societies – and especially their elites – are subject to an ever stronger pull in the direction of extrinsic values, educated elites within those societies have used and continue to use labels such as ‘shame-culture’ and ‘honor society’ to denigrate and patronize internal and external others – inner-city gangs, citizens of the US South (and their Scots ancestors), immigrants (e.g. the Irish and the Italians in the US), native Americans, the Japanese, southern Europeans, north Africans – and the ancient Greeks (to name but a few). Ancient Greek evidence on the nature of honor, by contrast, supports contemporary thought in a range of disciplines (such as developmental psychology, sociology, and political philosophy) on the interplay of esteem and self-esteem, recognition and dignity, as fundamental to social interaction in any society worthy of the name.

Honor is a topic on which a great deal has been written, but it remains very poorly understood. A typical failing is to ghettoize the phenomenon – as limited only to some forms of interaction (found in some contexts and not in others), as a concern only of one social stratum among many, as a male-gendered phenomenon, as a characteristic only of certain forms of social organisation. This can extend even to the claim that there are ‘honour societies’ that differ fundamentally from ‘dignity societies’ (echoing the older and now widely discredited antithesis between ‘shame cultures’ and ‘guilt cultures’). Such antitheses entail a distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic values that is useful for analysing individual tendencies and historical and cultural differences. But there is no group and no historical society (and perhaps, except in extreme pathological cases, no individual either) in which some combination of both tendencies is not found. Despite strong reasons for believing that contemporary Western societies – and especially their elites – are subject to an ever stronger pull in the direction of extrinsic values, educated elites within those societies have used and continue to use labels such as ‘shame-culture’ and ‘honor society’ to denigrate and patronize internal and external others – inner-city gangs, citizens of the US South (and their Scots ancestors), immigrants (e.g. the Irish and the Italians in the US), native Americans, the Japanese, southern Europeans, north Africans – and the ancient Greeks (to name but a few). Ancient Greek evidence on the nature of honor, by contrast, supports contemporary thought in a range of disciplines (such as developmental psychology, sociology, and political philosophy) on the interplay of esteem and self-esteem, recognition and dignity, as fundamental to social interaction in any society worthy of the name.

Douglas Cairns is Professor of Classics in the University of Edinburgh and author of Aidôs: The Psychology and Ethics of Honour and Shame in Ancient Greek Literature (1993), Bacchylides: Five Epinician Odes (2010), and Sophocles: Antigone (2016). His most recent edited volumes include Distributed Cognition in Classical Antiquity (with Miranda Anderson and Mark Sprevak, 2018), A Cultural History of the Emotions in Antiquity (2019), Emotions through Time: From Antiquity to Byzantium (with Martin Hinterberger, Aglae Pizzone, and Matteo Zaccarini, 2022), Contempt, Ancient and Modern (2023), and In the Mind, in the Body, in the World: Emotions in Early China and Ancient Greece (with Curie Virág, 2024). He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and of the British Academy, and a Member of Academia Europaea.

Co-sponsor: The Department of Classics

PAST EVENTS: AUTUMN 2023/SPRING 2024 PROGRAM

Tuesday, September 12, 2023, 4:00-5:30 p.m.:

“Merchants of the Right: Gun Sellers and the Crisis of American Democracy,” Jennifer Carlson, Assoc. Professor, Dept. of Sociology, University of Arizona

Location: 165 Thompson Library

Gun sellers sell more than just guns. They also sell politics. From the research behind her book Merchants of the Right, award-winning author Jennifer Carlson sheds light on the unparalleled surge in gun purchasing during one of the most dire moments in American history, revealing how conservative political culture was galvanized amid a once-in-a-century pandemic, racial unrest, and a U.S. presidential election that rocked the foundations of American democracy. Drawing on a wealth of in-depth interviews with gun sellers across the United States, Carlson takes readers to the front lines of the culture war over gun rights, offering crucial lessons about the dilemmas confronting us today, arguing that we must reckon with the everyday politics that divide us if we ever hope to restore American democracy to health.

About Jennifer Carlson

Jennifer Carlson is an Associate Professor of Sociology and a MacArthur Fellow (Class of 2022). Her work examines the politics of guns in American life. She is the author of Citizen-Protectors: The Everyday Politics of Guns in an Age of Decline (2015, Oxford University Press), Policing the Second Amendment: Guns, Public Law Enforcement and the Politics of Race (2020, Princeton University Press), and Merchants of the Right: Gun Sellers and the Crisis of Democracy (Forthcoming 2023, Princeton University Press). She is currently the principal investigator on a National Science Foundation grant examining the experiences of gun violence survivors in Florida and California.

Co-sponsors: Department of Political Science, Mershon Center, Department of Sociology

Monday, October 2, 2023, 4:00-5:30 p.m.:

“The Making of the Angry Chinese: Colonial Gaze, Anti-Colonial Sentiments, and the Rise of Chinese Nationalism,” Xin Fan, East Asian Studies, University of Cambridge

Watch video of this talk or listen to the audio here.

The vast distance between the Far East and the Far West is not only a gap in geography but also one in feelings. As early modern European thinkers failed to emotionally connect themselves to the Chinese body, they were debating the hypothetical question of killing a mandarin (Ginzburg, 1994; Hayot, 2009). This lack of sympathy continued to exist in the twentieth century, and it became a root of the Western bewilderment of the Chinese anger. To many, this anger seems to register an irrational, xenophobic aspect of Chinese nationalism engineered by the party state. Chinese propaganda further reinforces this stereotype, according to which Chinese people are always angry and their feelings are so easily hurt by foreign countries (King, 2017). Yet the making of the angry Chinese is more than just a state project. In this paper, I attempt to contextualize and humanize the Chinese anger by historicizing this emotional feeling to the live-or-die experience during the War of Resistance against Japan. As the case study on Ping-ti Ho’s critique of New Qing History shows, the cultural memory of the war and the emotional attachment to one’s culture together contributed to Chinese educated elite’s growing resentment against Western perspectives on China. The Chinese anger is not just a far cry of nationalist emotions but also a bodily experience of war and national survival.

About Xin Fan

Xin Fan is a Teaching Associate in Modern Chinese History at Cambridge University. His most recent publication is World History and National Identity in China: The Twentieth Century (Cambridge University Press, 2021). He also co-edited Receptions of Greek and Roman Antiquity in East Asia (Brill, 2018) with Professor Almut-Barbara Renger at the Free University Berlin. He is currently working on a book manuscript tentatively titled, “The Right to Talk about China: The Rise of Emotional Politics, 1900 to 1949,” as well as collaborating with scholars in Europe, America, and Asia on several projects on nationalism, historiography, and conceptual history.

Co-sponsors: Institute for Chinese Studies, Department of Political Science, Center for East Asian Studies, Mershon Center

Tuesday, October 24, 2023, 4:00-5:30 p.m.:

“OUR AGE OF ANGER: Can the Humanities Help?,” Owen Flanagan, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Philosophy, Duke University

Location: Colloquia Room (3rd Floor, 18th Ave. Library)

Watch video of this talk or listen to the audio here.

We live in what the novelist Pankaj Mishra calls “The Age of Anger.” In everyday life, we hear that we are entitled to our anger, that anger is an authentic expression of the self, and that we need to vent our anger. Is this true? Meanwhile, politics is increasingly a zone in which angry dismissive performance battles opposing angry dismissive performance. Can the humanities help? In this talk, I explore findings from emotion science and cross-cultural philosophy and offer ways to think critically about how we do anger in personal relations, commercial relations, and in political life. I make some suggestions for how we might do anger in more sensible and productive ways to increase both well-being and social justice.

About Owen Flanagan

Owen Flanagan is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Duke University. His work is in Philosophy of Mind and Psychiatry, Ethics, Moral Psychology, Cross-Cultural Philosophy. Some of his recent books are: The Geography of Morals: Varieties of Moral Possibility (Oxford University Press, 2016); The Bodhissattva’s Brain: Buddhism Naturalized (MIT Press, 2011); and The Really Hard Problem: Meaning in a Material World (MIT Press, 2007). He has lectured on every continent except Antarctica.

Co-sponsors: Center for Ethics and Human Values and the Department of Philosophy

Monday, November 13, 2023, 4:00-5:30 p.m.:

“Conceptual and Performative Variations in Practices of Anger: Are There Common Threads?,” William Reddy, Professor Emeritus of History and Professor Emeritus of Cultural Anthropology, Duke University

Location: Colloquia Room (3rd Floor, 18th Ave. Library)

Watch video of this talk or listen to the audio here.

In 2020, Thomas Dixon in an essay entitled “What Is the History of Anger a History of?” argued that the modern English word, anger, is “without a stable transhistorical referent.”1 A range of historical and ethnographic examples will be presented, and the extent to which they support Dixon’s thesis will be examined. While subscribing to Dixon’s methodological caveats, I suspect there may be some discernible transhistorical patterns: (1) The meanings of anger and its local equivalents across time and space exhibit uniformities common to emotion terms in many languages. Emotion terms are usually vague or multivocal and suggest multiple possible courses of action. (2) The emotional states designated by anger terms, as with most emotion terms, are subjects of effortful attempts at “regulation,” or “management” aimed not at faking but at transforming a genuine, if ambivalent, emotional response into a preferred (and often unambivalent) one. (3) Expressions of anger generally imply claims to a status of honor or authority higher than that of the person or persons targeted by these expressions, and are often closely associated with local concepts of humiliation and vengeance.

About William Reddy

William Reddy is the William T. Laprade Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History at Duke University. Some of his recent books include: The Making of Romantic Love: Longing and Sexuality in Europe, South Asia and Japan, 900-1200 CE (University of Chicago Press, 2012), and The Navigation of Feeling: A Framework for the History of Emotions (Cambridge University Press, 2001). His current research investigates the relationship between reason and emotion in the seventeenth century.

Co-sponsor: Department of Anthropology

Tuesday, January 23, 2024, 4:00-5:30 p.m.:

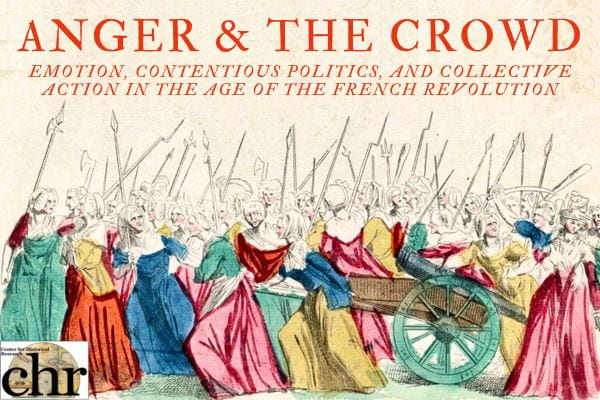

“Anger and the Crowd: Emotion, contentious politics, and collective action in the age of the French Revolution,” David Andress, Professor of Modern History, University of Portsmouth and Katie Jarvis, Assoc. Professor of History, University of Notre Dame, Margaret Newell (Moderator), Distinguished Professor of History, Ohio State Univ.

Watch video of this talk or listen to the audio here.

From the Revolution’s earliest days, crowds were pivotal. A Parisian crowd toppled the symbol of the Old Regime’s despotism: the Bastille. A crowd led by Parisian market women brought the revolutionary National Assembly and the royal family away from the palace at Versailles and into the heart of the capital of Paris. Throughout the decade that followed, the Revolutionary crowd remained a significant political force—one to which the elected leaders in the National Assembly listened.

Understanding the formation, psychology, communication, and political aims of the revolutionary crowd has been a subject of scholarly study for at least fifty years. Recent work has made clear that peaceful collective action was a hallmark of the Revolution. Nevertheless, the specter of political violence remains in the ways that the Revolution is remembered—the linking of political violence and crowds so vividly rendered by early critics, such as Charles Dickens and Edmund Burke, has continued to resonate. Moreover, collective action remains an important locus of political communication and activity today.

The French Revolutionary crowd is an especially rich case for considering up close the connections between collective action, democracy, and the power of emotion.

Co-sponsor: Department of French and Italian

Tuesday, February 13, 2024, 4:00-5:30 p.m.:

“The Eloquence of Anger: Zulu Ngoma Men’s Song and Dance,” Louise Meintjes, Professor of Music & Cultural Anthropology, Duke University

Watch video of this talk or listen to the audio here.

For Zulu ngoma performers, responsible manhood entails crafting anger into eloquence. In so doing, performers blur the lines between pain and styling, violence and its performance. When song and dance are limned by violence, how might we think about histories of anger acting upon the world through art? Living with the legacies of apartheid, ngoma performers’ anger (“ulaka”) is an expressive resource and a necessary though ambiguous response to injustice.

About Louise Meintjes

Louise Meintjes is the Marcellor Lotti Professor of Music and Cultural Anthropology at Duke University. Some of her recent publications include: Dust of the Zulu: Ngoma Aesthetics after Apartheid (Duke University Press, 2017) and Sound of Africa!: Making Music Zulu in the South African Studio (Duke University Press, 2003).

Co-sponsors: Department of Anthropology and Musicology in the School of Music

Tuesday, March 5, 2024, 4:00-5:30 p.m.:

“Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger: A Conversation with Rebecca Traister”

Rebecca Traister, Writer at large for New York Magazine

with Treva B. Lindsey, Professor, Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies, The Ohio State University

Location: Hagerty Hall, Room 180

(This talk was not filmed.)

Gramercy Books will be at the event to sell Rebecca Traister’s latest book: Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger (2018)

A New York Times best seller, Good and Mad tracks the history of female anger as political fuel—from suffragettes marching on the White House to office workers vacating their buildings after Clarence Thomas was confirmed to the Supreme Court. Traister explores women’s anger at both men and other women; anger between ideological allies and foes; the varied ways anger is received based on who’s expressing it; and the way women’s collective fury has become transformative political fuel. She deconstructs society’s (and the media’s) condemnation of female emotion (especially rage) and the impact of their resulting repercussions. The book was published in 2018, in the same week that Christine Blasey Ford testified at Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings, and portions of it were read into the Congressional record on the day that Kavanaugh was confirmed.

About Rebecca Traister

Rebecca Traister is writer at large for New York magazine. A National Magazine Award winner, she has written about women in politics, media, and entertainment from a feminist perspective for The New Republic and Salon and has also contributed to The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times and The Washington Post. She is the author of Good and Mad and All the Single Ladies, both New York Times best-sellers, and the award-winning Big Girls Don’t Cry.

Co-sponsors: Department of English, Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies and the School of Communication

AUTUMN 2024 PROGRAM

Mon., Sept. 9, 2024 – 4:00 to 5:30:

“Anger Management: Dignity, Indignity and the Rhetoric of Resentment,” Robert A. Schneider, Professor of History, Indiana University Bloomington

Location: Colloquia (3rd floor) at the 18th Ave. Library

View video of the presentation.

![]()

Psychologists and advice columnists tell us that anger is not good—it’s not good for us and it’s worse for those around us. But political anger—that is, the collective expression of angry discontent—surely can be, and has been, effective as a tool for asserting grievances and making claims. In any case, whatever its virtues or liabilities, anger seems to be all-pervasive in our contemporary political culture. We are in, according to Pakaj Mishra, an “Age of Anger.”

In this presentation, I will explore a variety of ways anger and resentment have been deployed, emphasizing not so much “anger” itself—that is, the raw emotion—but rather the modes and means by which anger is expressed or performed. In part, this will be an exploration of the rhetoric of anger (or resentment), looking at how various writers have themselves thought hard how to “be angry” while preserving a measure of dignity. Indeed, for some, especially in the tradition of Black Liberation, from Frederick Douglass to Martin Luther King, Jr., to present themselves in a “dignified” way seemed as important, perhaps even more, than to make a display of their anger. And this is largely true with other collective struggles in the West, including labor movements and the campaign for women’s rights. Since the 1960s, however, the tendency to yoke anger to dignity has seemed to prevail less and less. Instead, “dignity” has been increasingly eclipsed by “self-expression.” Today, commentators like Vincent Lloyd (Black Dignity, Yale, 2022) argue for a very different conception of dignity, one which calls into question traditional, largely liberal, notions of dignity as undermining the quest for liberation.

Robert A. Schneider is a Professor of History at Indiana University Bloomington. He is the author of four books, most recently The Return of Resentment: The Rise and Decline and Rise Again of a Political Emotion (Chicago, 2023). He has received grants and fellowships from the Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the French Government (Bourse Chateaubriand). He has been a visiting fellow at All Souls College and Oriel College, both at the University of Oxford; a visiting lecturer at Ecole des Hautes Etudes Paris (three times); and a visiting scholar at Bristol University, the Université de Toulouse, and the University of Pennsylvania. From 2005 to 2015 he was Editor of the American Historical Review.

Co-sponsors: Department of Political Science; Mershon Center

Mon., Oct. 7, 2024 – 4:00 to 5:30:

“Bruegel’s Anger,” Mitchell Merback, William Arnell and Everett Land Professor, Art History, Johns Hopkins University

Location: Colloquia (3rd floor) at the 18th Ave. Library

View video of the presentation.

![]() At the start of his career, Pieter Bruegel’s anger (Ira) appears in allegorical guise, trodding a landscape cluttered with the follies, perversities, and monstrosities his reign on earth has unleashed. Capitalizing on the craze for works in the manner of Bosch, the engraving, part of a series of the Virtues and Vices, was no doubt a money-maker and a boon for the young Antwerp painter. But how much of Bruegel’s own outlook on anger does it convey? With the exception of another early work, the personification of martial fury known as Dulle Griet (“Mad Meg”), anger practically disappears from Bruegel’s oeuvre. Yet this absence deceives us if we regard anger only as moralizing subject. Anger remained a potent preoccupation in Bruegel’s art, not as a social evil to be combatted but a passion of the soul in need of remedy. Bruegel’s modern interpreters have sought the coordinates of his philosophical outlook in the humanist circle of Abraham Ortelius and its non-partisan Spiritualism, a worldly piety informed by Christian Stoicism. As the Low Countries erupted in religious factionalism, civic unrest, iconoclasm, and inquisitorial terror — the time Bruegel’s career was cresting — consolation was sought in the works of Cicero and Seneca, who recommended the practice of philosophia to combat the deformations wrought by anger. Bruegel depicted the triumph of death over humanity, the shunning of Christ by Christians, and slaughter of the Bethlehem’s innocents without a hint of anger. Was that attitude irenic, ironic, or medicinal?

At the start of his career, Pieter Bruegel’s anger (Ira) appears in allegorical guise, trodding a landscape cluttered with the follies, perversities, and monstrosities his reign on earth has unleashed. Capitalizing on the craze for works in the manner of Bosch, the engraving, part of a series of the Virtues and Vices, was no doubt a money-maker and a boon for the young Antwerp painter. But how much of Bruegel’s own outlook on anger does it convey? With the exception of another early work, the personification of martial fury known as Dulle Griet (“Mad Meg”), anger practically disappears from Bruegel’s oeuvre. Yet this absence deceives us if we regard anger only as moralizing subject. Anger remained a potent preoccupation in Bruegel’s art, not as a social evil to be combatted but a passion of the soul in need of remedy. Bruegel’s modern interpreters have sought the coordinates of his philosophical outlook in the humanist circle of Abraham Ortelius and its non-partisan Spiritualism, a worldly piety informed by Christian Stoicism. As the Low Countries erupted in religious factionalism, civic unrest, iconoclasm, and inquisitorial terror — the time Bruegel’s career was cresting — consolation was sought in the works of Cicero and Seneca, who recommended the practice of philosophia to combat the deformations wrought by anger. Bruegel depicted the triumph of death over humanity, the shunning of Christ by Christians, and slaughter of the Bethlehem’s innocents without a hint of anger. Was that attitude irenic, ironic, or medicinal?

Mitchell Merback is the William Arnell and Everett Land Professor in Art History at Johns Hopkins University. His art-historical work centers on northern Europe during the Later Middle Ages, Early Modern and Reformation periods, with the arts of Germany, Austria, the Low Countries and France comprising the principal arena of investigation. His publications include: Perfection’s Therapy: An Essay on Albrecht Durer’s Melencolia (Zone Books, 2017), Pilgrimage and Pogrom: Violence, Memory and Visual Culture of the Host-Miracle Shrines of Germany and Austria (University of Chicago Press, 2013), and Beyond the Yellow Badge: Anti-Judaism and Antisemitism in Medieval and Early Modern Visual Culture (Brill, 2008).

Cosponsored by the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, the Department of Art History, and the Department of Germanic Languages and Literature.

Mon., Nov. 18, 2024 – 4:00 to 5:30:

“Righteous Anger as a Political Emotion: Jews, Arabs, and the Question of Palestine, 1947-1949,” Derek Penslar, William Lee Frost Professor of Jewish History and the Director of the Center for Jewish Studies, Harvard University

Live Streamed via Zoom.

View video of the presentation.

![]() Anger is an emotional response to an unmet desire, a protest against deprivation. Righteous anger, also known as indignation, asserts the right to that which has been denied to a person. Like other feelings, righteous anger can be scaled up from the realm of individual interaction to that of the collective. In domestic and international politics, the performance of righteous anger anchors an interest group and legitimizes its cause, especially when it is in conflict with other actors. This talk analyzes the role of righteous anger in Jewish and Arab discourse on the disposition of Palestine between 1947 and 1949. During the debates at the United Nations about the Palestine Question in 1947, both sides claimed to have been overlooked and betrayed by the international community. Their indignation was a protest against the indignity that had been visited upon them (by antisemitism and colonialism respectively) and an assertion of entitlement. The 1948 war only deepened each side’s grievances and belief in its own righteousness. As the subsequent history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has demonstrated, righteous anger is a durable political emotion that can be transmitted across generations.

Anger is an emotional response to an unmet desire, a protest against deprivation. Righteous anger, also known as indignation, asserts the right to that which has been denied to a person. Like other feelings, righteous anger can be scaled up from the realm of individual interaction to that of the collective. In domestic and international politics, the performance of righteous anger anchors an interest group and legitimizes its cause, especially when it is in conflict with other actors. This talk analyzes the role of righteous anger in Jewish and Arab discourse on the disposition of Palestine between 1947 and 1949. During the debates at the United Nations about the Palestine Question in 1947, both sides claimed to have been overlooked and betrayed by the international community. Their indignation was a protest against the indignity that had been visited upon them (by antisemitism and colonialism respectively) and an assertion of entitlement. The 1948 war only deepened each side’s grievances and belief in its own righteousness. As the subsequent history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has demonstrated, righteous anger is a durable political emotion that can be transmitted across generations.

Derek Penslar is the William Lee Frost Professor of Jewish History and the Director of the Center for Jewish Studies at Harvard University. His books include Jews and the Military: A History (2013), Theodor Herzl: The Charismatic Leader (2020; German ed. 2022); and Zionism: An Emotional State (2023). He is currently writing a book titled The War for Palestine, 1947-1949: A Global History. He is a past president of the American Society for Jewish Research, a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and an Honorary Fellow of St. Anne’s College, Oxford.

Co-sponsors: Near Eastern & South Asian Languages and Cultures, the Melton Center, and the Mershon Center