Check this page for posts about livestock and forage production.

Hello! My name is Christine Gelley. I am the Ohio State Agriculture and Natural Resources Extension Educator for Noble County. My job is to serve the people of Ohio with educational outreach programs and individually tailored resources based on timely, reliable, researched, and unbiased information. I have a background in Agronomy, specifically Forage Quality and Management with degrees from The Ohio State University and the University of Tennessee. Additional areas of interest include management of grazing animals, weeds and insect pests, horticulture, farm safety, forestry, and wildlife.

Hello! My name is Christine Gelley. I am the Ohio State Agriculture and Natural Resources Extension Educator for Noble County. My job is to serve the people of Ohio with educational outreach programs and individually tailored resources based on timely, reliable, researched, and unbiased information. I have a background in Agronomy, specifically Forage Quality and Management with degrees from The Ohio State University and the University of Tennessee. Additional areas of interest include management of grazing animals, weeds and insect pests, horticulture, farm safety, forestry, and wildlife.

If you are viewing this page, we likely met at Farm Science Review or a Forage Field Day. Please scroll down to browse a variety of materials about forages including the topics featured at Farm Science Review. Feel free to contact me for more information by leaving a comment, emailing gelley.2@osu.edu, or calling the Noble County OSU Extension Office at 740-732-5681.

Grasslands: Carbon Neutral Before It Was Cool

Click the links below to explore articles that complement the presentation given during Farm Science Review 2022 by Ms. Christine Gelley on the value of Native Warm-Season Prairie Grasses in the quest for “Carbon Neutral Agriculture”:

http://www.geotimes.org/jan02/feature_carbon.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/2020/08/19/climate-change-prairie/

https://climatechange.ucdavis.edu/climate/news/grasslands-more-reliable-carbon-sink-than-trees

https://extension.psu.edu/how-forests-store-carbon

Continue to scroll to find more information about warm-season native grasses.

Synchronized Reproduction & Grazing Rotations for Small Ruminants

Click the link below to view the PDF version of the presentation given during Farm Science Review 2021 by Dr. Brady Campbell and Ms. Christine Gelley.

Click Here: FSR_Synchronized Reproduction & Grazing Rotations_2021

OSU Small Ruminant Webinar Video Scripts

Click the links below to view the written script of the two nutrition videos presented by Dr. Alejandro Relling on February 16, 2021 during Webinar 2 of the OSU Small Ruminant Webinar Series. YouTube links are included.

Click Here: Ale_Fiber_Gestating_Ewes_Script

Click Here: Ale_Fiber_Growing_Lambs_Script

Coshocton County Pasture Walk Resources

Are you interested in learning more about how to plant, manage, and identify warm-season perennial grasses?

Investigate these resources from the Center for Native Grasslands Management:

Most are oriented to site conditions in Tennessee; however the concepts are the same for Ohio. The calendar dates may need adjusted slightly for your location. Check the Ohio Agronomy Guide for recommendations or contact Christine Gelley to converse about your site.

- Establishing Warm-Season Perennials: http://nativegrasses.utk.edu/publications/PB-1873-Native-Grass-Forages.pdf

- Weed Competition Control (Herbicide Recommendations): http://nativegrasses.utk.edu/publications/SP731-F.pdf

- Seedling I.D.: http://nativegrasses.utk.edu/publications/SeedlingIDGuideforNativeGrassesSoutheast.pdf

- Grazing Management: http://nativegrasses.utk.edu/publications/SP731-C.pdf

- Hay Management: http://nativegrasses.utk.edu/publications/SP731-D.pdf

- Adjusting Cutting Height: http://nativegrasses.utk.edu/publications/SP731-I.pdf

Morrow County Forage Field Day Resources

Christine’s presentation on Herbicide Selection presented at the field day is available as a pdf. Click here: Weed ID and Control Options-2mtd26q, Herbicides for Spot Spray-Rate per Gallon 2017-1kt7osl, Pasture Herbicide Use + Grazing Restriction 2017-2gk2xvx

Teff Grass is a Tough Grass to Surpass

Another version of this article by Christine Gelley was originally published by Farm and Dairy on July 26, 2018.

The first time I was introduced to the forage Eragrostis tef (common name Teff grass), I was in the front row of Dr. Gary Bates’ class in the Ellington Plant Sciences building at the University of Tennessee.

Dr. Bates is the Forage Specialist for UT Extension and the Director of the UT Beef and Forage Center. He is a well-regarded teacher, researcher, and writer. As one of my many influential mentors, I take his opinions to heart and still remember what he had to say about Teff grass.

Dr. Bates said, “Teff grass is one of those grasses that you just want to roll around naked in.”

A point that would be hard to argue with, since one of its common names is “Lovegrass” and the origin of the word “Teff” is the Ethio-Semitic word for “lost”. Which, seems to be justification enough for Dr. Bates’ opinion if you put two and two together. A sward of Teff grass is a beautiful green sea of soft textured forage. Ideal for animals to eat and not a bad place for a “picnic” either. It is hard not to love.

Teff grass originates from Ethiopia. It is a warm-season annual grass that can be used for hay, silage, or pasture. It is fast growing, high yielding, and a forage of excellent quality. It can be fed to horses, sheep, dairy and beef cattle. Teff can be used to boost summer production, tolerate drought, persist through waterlogged conditions, as a green manure, a double crop for cereal grains, or to aid in the rotation between newly seeded permanent pastures.

The greatest challenge producers will encounter is initially planting it.

Soil temperature is critical and must be above 65 degrees Fahrenheit. Teff cannot tolerate frost, so planting too early can be detrimental to a germinated stand and the stand will die out after the fall’s first frost. No need to fear if animals are grazing when frost comes through, because unlike some other warm-season annuals, Teff does not have issues with prussic acid accumulation after frost.

Seed bed preparation is another crucial step. Teff grass seed is very tiny, so a firm seed bed must be provided. Tillage and cultipacking are recommended. Controlling weeds prior to planting is also part of the process, because the early part of seedling development is dedicated to root growth, not shoot growth. The typical seeding rate for Teff is five to seven pounds per acre.

One of the benefits of Teff is that fertility needs are comparably low to other annual forages. Typical fertilizer application is about 60 pounds of nitrogen per acre at planting and 30-60 pounds after first cutting. Ideal pH for Teff is 6.0-6.5.

Hay production is the most common use for Teff. It should be harvested before going to seed and at heights of about 15 inches. Remaining stubble should be 4-5 inches. In years of adequate rainfall, two to three harvests can be completed in the growing season. Due to the fine texture of the stems, Teff grass dries faster than other annuals and should be baled at 20 percent moisture for square bales and 18 percent for round bales.

Grazing can be done successfully by multiple species, but pasture managers need to be observant of the pasture condition. Especially, early in the growing season. Tender seedlings can be pulled out of the ground or trampled if over-grazed.

If Teff grass sounds like an intriguing option for your forage system, OSU Extension invites you to come out and see a stand for yourself. Teff grass will be one of the forages planted at the Gwynne Conservation Area and on display during Farm Science Review from September 18-20. Forage and grazing talks will be offered throughout the day and personnel nearby to help answer producer questions.

If you are curious about testing Dr. Bates’ statement, we do ask that all of the visitors keep their clothes on and refrain from rolling around in the forage demonstration plots. We encourage you to try that once your stand is established at home.

Hope to see you there!

Special thanks to Dr. Gary Bates for allowing me to share this true story with you. Additional information about Teff grass can be gathered for you through your local Extension office.

When Rain Wreaks Plans for Pastures

Another version of this article by Christine Gelley was originally published by The OSU Sheep Team on July 3, 2018.

Mud, nutrient leaching, and erosion are a few of the ailments pastures across our region are experiencing in 2018. It can be a challenge to be thankful for rain in years like this. You’ve likely witnessed it wash away freshly planted seed, topsoil, and nutrients while trudging through swamps that should be access roads, watching seed heads develop on valuable hay, and cutting fallen limbs off damaged fence.

Nature has taunted many this season. In Southeast Ohio, opportunities to make hay have been few and far between due to soggy soil conditions and high humidity. The longer harvest is delayed, the poorer nutritive value becomes. Most producers have probably harvested first cutting hay that will barely meet requirements for animal maintenance. Looking beyond the frustration to solutions, there are things we can do to relieve the pressure that heavy rainfall inflicts on hayfields and grazed pastures.

Mud Management

One of the best ways to manage mud in grazing situations is to keep animals moving and give pastures rest. Split large paddocks into smaller paddocks and rotate animals frequently. Fence out areas that are extremely wet. Both practices reduce damage from hoof traffic.

Rotating animals among smaller paddocks will also make manure distribution more uniform and help prevent erosion. Adjust rotation lengths and stocking densities to keep forage vegetative. If seed heads develop during the rest period, make plans to come back and clip them when the ground is dry. Clipping will re-stimulate the plants and lower your risk for fescue toxicity issues later on.

If you must take equipment into the pasture, opt for smaller loads and use extreme caution on slopes. Use light implements that have tires with substantial surface area. If you get stuck, get help early. The harder you try to get unstuck alone, the harder it will be for someone to help you.

Nutrient Management

Having a good stand of legumes (20 percent or more) in the pasture can help replace leached nitrogen and reduce the need for a nitrogen application. Stands that are primarily grasses will be drastically improved with split applications of nitrogen.

Nitrogen is removed from pastures through volatilization, harvest, and leaching. Hay fields will have a more crucial need for nitrogen than grazed pastures, because the forage is removed from the site, rather than replaced by nitrogen in urine and manure.

An application between first and second cutting can be beneficial if volatilization risks can be reduced. A third application could also be useful if there is intent to stockpile the forage for late fall or winter grazing. The amount needed depends on yield goals, actual forage removal, spring fertilization, soil pH, and grass species.

Grazed pastures may need additional fertilizer part way through the growing season as well, but no more than one third of the pasture should be fertilized at a time to lower risks of nitrate toxicity for grazing animals.

Flood Conditions

If your pasture goes from soggy to flooded, keep in mind that water flow patterns can flush soil, weed seeds, manure, and microbes into the pasture and cause concerns for animal health.

If deposited silt levels are too high, animals may accidentally consume substantial amounts while grazing, which can cause digestive issues.

Weed seeds can be swept into the pasture and establish themselves in the damaged areas, crowding out the desirable forages during flood recovery. Detrimental weeds taking over damaged areas will reduce intake of high quality forages and may pose risks if poisonous plants become established. In times of pasture stress, animals are more likely to consume poisonous plants in an effort to find enough to eat.

Microbes and parasites are also easily transported into grazing pastures if water flows through an area of manure or sewage storage. It would be best to wait a week or two to return animals to pastures that have been flooded with tainted water. This will help maintain good herd health.

Once the water has drained from the pasture and the soil, investigate if there are any management decisions you could make now to reduce damage if a duplicate flooding event occurred. Consider reseeding heavily damaged areas. Choose varieties that will withstand the conditions of your operation.

Consider planting an annual forage to compensate in such areas as an emergency crop while you plan for the long term. Planting an annual forage will reduce further erosion, provide competition for weeds, and supply feed for animals more quickly than perennials. Annual ryegrass offers excellent tolerance to poorly drained soils, wheat has good tolerance, while oats, rye, and sorghum-sudangrass offer fair tolerance.

Don’t forget to eliminate standing water whenever possible to prevent mosquito development and reduce the risk of disease transmission for both animals and people.

For more information about the topics covered in this article, consult the following fact sheets from OSU Extension:

Fertility Management of Meadows- https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/anr-5

Preventive Measures for West Nile Virus- https://vet.osu.edu/extension/preventive-measures

Sacrificing Clovers for the Greater Good

Submitted to Ohio Farmer, OSU Beef Team Newsletter, & OSU Sheep Team Blog on April 16, 2018

As our world becomes increasingly connected, weed pressures and populations continue to expand. The diversity of a typical mid-west pasture creates difficulties when it comes to dealing with weed populations. These pastures usually contain a mixture of grasses, legumes, and forbs, some of which are beneficial and some of which are weeds. Eliminating the weeds while preserving the beneficials is a challenge and sometimes a sacrifice needs to be made for the greater good of the pasture and in turn, your livestock.

The list of weeds you may find in your pasture is nearly endless. Some of the most ominous weeds in Ohio pastures are Palmer amaranth, thistles, marestail, and coming soon to a pasture near you- spotted knapweed. Due to their ability to prolifically reproduce, these weeds become big problems fast.

Graziers tend to use cultural or mechanical controls to address weeds first. Mowing can be effective if timed appropriately. Amending the soil is often essential. Chemical control is sometimes the last resort due to fear of harming the good grass or clovers. While no method will give you 100% weed control, your best chances are achieved with a combination of all three.

Sometimes it is more economical to sacrifice your clovers than to preserve them. Those weeds mentioned earlier are bad news for pasture sustainability. A single female Palmer amaranth plant has the potential to produce half a million seeds. The herbicides that will kill Palmer amaranth, marestail, thistles, and spotted knapweed must be applied early in weed development and will probably cause significant harm to your legume stand.

Timing is crucial for controlling aggressive weeds. For example, the best chance you have for treating Palmer amaranth is to act when it is three inches or shorter and this window narrows rapidly, because it can grow up to three inches a day.

If mechanical control is employed, it must be accomplished before seed heads develop on the plant. Weeds rarely develop at the same rate or grow to the same heights. Some of the difficulties with mechanical control include setting the appropriate height for mowing, allocating time to clip pastures, and the cost of fuel to make multiple passes over the pasture. More frequent mowing will lead to greater success.

As mentioned previously, no method alone will provide complete control. Even in low input systems, chemical controls may be economical and efficient tools.

There are no broadleaf herbicides available right now that are safe for clovers. Dow AgroSciences has a herbicide currently in development that has shown promise for safe use on white clover, but it will likely be a few more years before it hits the market.

If you realistically weigh the risks, you could be fighting a losing war with weeds for years hanging onto that clover stand. Or you could sacrifice the clovers, use a tested and recommended herbicide, and replace the clovers the following year. No-till drills are wonderful tools for planting clovers in the fall. Frost seeding is also relatively easy for clovers.

Dutch clover is the most commonly found clover in perennial pastures, but it’s value is often overestimated. Dutch clover is persistent and spreads easily. However, in comparison to improved clover varieties Dutch clover falls short in yield and quality. Replacing Dutch clover with improved varieties of white clover, such as Ladino clovers, can improve the value of the pasture sward.

Introducing freshly inoculated seed can also improve nitrogen fixation in the pasture. If fertilizer is needed, it can be broadcast with clover. Avoid seeding clovers directly into freshly spread manure.

Always follow the label when mixing and applying herbicides. Many weeds are resistant to commonly used products. Check the label before purchasing for the effectiveness rating on your problem weeds. Typically, the ratings indicate percentage of control. Look for products that will have 90% control or better. Also, be sure to use the appropriate rates. Under applying herbicides increases the development of resistant weeds.

For more information about forage and herbicide selection, weed identification and control, and general pasture improvements, consult your local Extension office. A pasture walk with a professional can be the most effective tool for pasture improvement.

Forage News, Frostbite, and Fescue Foot

Another version of this article by Christine Gelley was originally published by the Ohio Beef Cattle Letter on January 22, 2018.

In January, I had the opportunity to attend the American Forage and Grassland Council Annual Conference with some of our other Ohio Extension Educators. It was a wonderful experience to learn from others and share what we have learned with forage producers and professionals across the country.

Two sessions that specifically caught my interest were “Managing Clovers in the 21st Century” and “Understanding and Mitigating Fescue Toxicosis.” Both are struggles for many producers in my region of Ohio.

The clover session included a presentation by Dow Agrosciences about a new product they are developing for treating broadleaf weeds in clover stands. It was definitely intriguing and encouraging. Hopefully, in a couple years it will be available on the market. Broadleaf weed control is a challenge for most forage producers. Having more tools in the tool box would certainly be helpful in fixing up pastures.

More tools would also be welcomed for understanding and mitigating the impacts of tall fescue on the livestock industry. Although we have known about the endophytic fungus that lives within the plant for half a century, it continues to puzzle livestock and forage managers. Producers in the fescue belt of America have learned to live with it and how to improve management.

We have discovered that the concentration of the endophyte changes throughout the growing season. Researchers worked diligently to develop endophyte-free and novel endophyte varieties. Many producers have turned to dilution to be the solution by incorporating more legumes and other grasses into the pasture. However, it is still estimated that effects of fescue toxicosis cost the U.S. Beef Industry alone between $500 million and $1 billion dollars each year.

Usually we discuss the issues of fescue endophyte in the context of mid-summer management. The endophyte accumulates in seed heads of mature plants and is accentuated in drought conditions. Since many other common grasses go dormant in that situation, fescue may be the only thing left to eat. Symptoms of distress due to the fescue endophyte include: decreased appetite, laziness, overheating, and in severe cases, loss of circulation to body extremities and/or the fetus of a late gestational animal.

In the fescue toxicosis session at the conference, we were reminded to watch for fescue foot in winter. The decreased circulation that results from the constricted blood vessels in the animal makes them increasingly susceptible to frostbite.

Frostbite can easily go unnoticed in snowy and cold situations and could even lead to gangrene. If this occurs, the appendage (foot or tail) could be lost and it is likely the animal will need to be culled. This is usually a problem that starts in summer and carries into winter. In most cases, the concentration of the ergot alkaloids that cause these symptoms is low in dried mixed hay. Even so, this is a condition to scout for during winter.

The bitter cold we have experienced this year in combination with great volumes of snow increases the chances for animals to have frostbite damage. While you work your livestock, be sure to check feet and tails for signs of frostbite. If you do see it, contact your vet ASAP.

I hope that no one encounters a fescue foot turned frostbite injury. If you do, take steps to make improvements to your forage supply. There are ways to mitigate the impacts of fescue endophyte on your livestock in all seasons. I am confident that your county extension office would be interested to know and eager to assist you in making crutial decisions about living in harmony with tall fescue.

There is still a lot of winter left. I hope Mother Nature will be kind as we venture forward.

An example of fescue foot injury on cattle.

Photo by: Dr. David Bohnert, Oregon State University

Who is in Control, You or Your Forage?

Another version of this article by Christine Gelley was originally published by Farm and Dairy on January 11, 2018.

January is often a month of resolutions. The turn of the New Year inspires many to take back control of some aspect in their life and improve on it. Realigning our focus is a good thing. Reevaluating our execution is as well. Have you done that lately when it comes to how you manage your forages?

You may be familiar with the equation: E + R = O

The initial credit for this equation goes to Dr. Robert Resnick, but about five years ago, Ohio State Head Football Coach Urban Meyer drew attention to it for his players with the equation printed on rubber wristbands. The rest of the University ran with it as well, distributing wristbands to staff and students.

The “E” stands for “event”. The “R” stands for “response”. The “O” stands for “outcome”. The general idea with this equation is that you cannot control the events that come your way, but you can control your response to create a positive outcome. The response you put forth is completely your responsibility. This equation can practically be applied to any situation. In the context of this article, the situations faced while managing forages.

Now, there is a distinct difference in being proactive and being reactive. Being proactive means you anticipate future problems, needs, and changes so that you can be prepared when something influential occurs. Being reactive means you take action after a triggering situation. In order to maintain control of your forage system in an uncontrollable world, you need to be good at being both proactive and reactive.

Pasture management is reliant on and also most complicated by the same uncontrollable factor-the weather. Despite our advances in meteorology, it is impossible to know exactly what will happen or when. Floods, droughts, cold spells, hot spells, tornadoes, earthquakes, ice storms, blizzards, and more can pop up unexpectedly and disrupt management plans.

Inevitably, forage production is dependent on the weather and forage managers are dependent on forage production. Your livestock and/or customers are dependent on your decisions managing that forage production in order to nourish their bodies and keep the cycle intact. So who is controlling who? Are you controlling the forage or is it controlling you? In other words are you managing in a manner that leans more towards proactive or reactive?

Some examples of ways you can be a proactive forage manager are:

- Making a grazing plan. This is the ideal plan. If everything in the system was just right, you would get the outcome you are looking for.

- Draw out a map. Map where your water sources are, your fence, your gates, your hay storage, your livestock handling facilities, your equipment, and your paddocks.

- Make contingency plans. Identify the chain of events that would transpire if a component of that plan failed. Think about the “what ifs” and identify limitations of the system.

- Find ways to compensate for the limitations of the system.

For example: If your most productive pasture in in a low lying area, plan a route to move animals to higher ground in the case of a flood and store supplemental hay on the high ground.

Another example: If drought ensues and your forage goes dormant, have a paddock of drought tolerant forage available or be prepared to feed supplemental hay or grain.

- Essentially, expect the unexpected.

Those contingency plans are what help you in reactive situations. When an unexpected event transpires, you can more easily develop solutions to problems. You can maintain control of your forage system, rather than it controlling you. Consider adopting the E + R = O equation as your New Year’s Resolution.

To conclude, do not wait around to see if 2018 will be a good year, make it a good year. After all, you control the outcome. Stay warm, stay safe, and stay positive this winter!

For more information about creating grazing and contingency plans that fit your system, contact your local Extension Educator and Soil & Water Conservation District.

Management Considerations for Warm-Season Perennials

The information presented here was originally formatted for an Ohio State Extension Staff In-Service in June 2016 by Christine Gelley and was most recently updated for Farm Science Review Sept. 19-21, 2017.

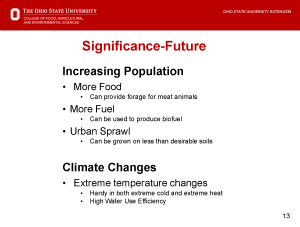

During my graduate program at The University of Tennessee there was a defined interest in utilizing warm-season perennial grasses as grazing pasture for beef cattle. One of the greatest influences for this interest is persistence during high heat and drought tolerance. The same could be applied for Ohio.

Although our number of growing degree days are fewer than producers have in the South, we are still capable of incorporating warm-season perennials into our grazing systems. We also experience periods of high heat and drought. Our typical sources of grazing pastures are cool-season grasses (ex: tall fescue, orchardgrass, ryegrass, timothy) and legumes (ex: white clover, red clover, alfalfa), which are much less hardy than the grasses discussed here. Part of the reason is the way the plants photosynthesize (a.k.a. turn light into food), how they utilize water in the process, and differences in structural growth. Warm-season grasses are more efficient photosynthesizers, however the forage they produce in the process is of lesser nutritive value than cool-season grasses.

The trade off can be worthwhile in times of stress, on marginal sites, remediation, and for wildlife enthusiasts. Forage of less then ideal nutritive value that is available is more valuable to grazing livestock than no forage at all. The greatest advantages of including warm-season perennials in a grazing system are the ability to combat “summer-slump”-the time in mid-summer when our cool-season plants tend to go dormant until cooler, wetter weather returns, drought tolerance when water is scarce, and the ability to extend the grazing season, which in turn means feeding less hay.

In addition, warm-season perennial grasses produce large amounts of dry matter for animals to consume with little inputs. Fertilizer needs are low, water needs are low, there are few pests or pathogens that are threats, and they can withstand vast changes in weather.

Some of the limitations of establishing these grasses are lack of available improved varieties for specific regions, slow establishment rates, they mature quickly, and they cannot tolerate close grazing.

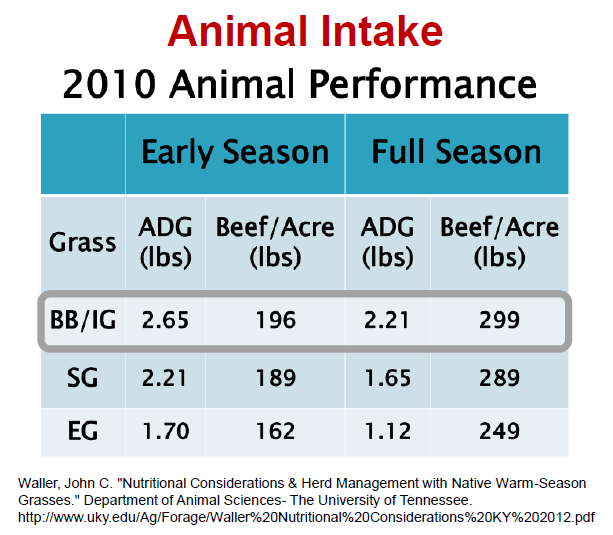

Although animal intake is typically lower for these grasses than we see with our traditional options, animal intake and weight gain can still be sufficient for achieving production goals when managed for both the plant and animals’ success.

Not all species and varieties of warm-season perennial grasses are created equal. Research available varieties suited for your conditions, buy high quality seed, and start with good seedbed preparation. One of the greatest struggles of managing these grasses is weed control. Start clean of weeds and stay clean to hasten establishment. Here are some of the details of the four most common warm-season perennial grasses:

Find a more detailed presentation of this information here: warm-season forage presentation-2m14gpz

The University of Tennessee has a collection of well-done resources about native warm-season grasses. Browse through for general information and recommendations, but remember to verify details for your region. View UT’s Resources HERE.

Grazing Corn, Sorghum x Sudangrass, and Winter Wheat

The information presented here was gathered and formatted by Christine Gelley for Farm Science Review Sept. 19-21, 2017.

View OSU Extension’s Factsheet Using Corn for Livestock HERE.

Citations:

- https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/anr-11

- http://beef.unl.edu/oats-and-turnips-for-fall-grazing

- http://www.agtest.com/articles/FEED%20AND%20FORAGES%20CALCULATIONS_new.pdf

- http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/pdf/10.4141/cjps2012-094

- http://practicalfarmers.org/app/uploads/2015/07/Combining-CC-and-Livestock.pdf

- http://beef.unl.edu/documents/2017-beef-report/201716-Nutrient-Content-of-Summer-Planted-Oats-a-er-Corn-Harvest-and-Grazing-Performance.pdf

- https://www.extension.iastate.edu/sites/www.extension.iastate.edu/files/iowa/SudanFS50.pdf

- http://www.grainandgraze3.com.au/resources/171_Choiceofforagecropsforwinterfeed.pdf

- http://www.midwestforage.org/pdf/927.pdf.pdf

- http://www.beefmagazine.com/sites/beefmagazine.com/files/2016-feed-composition-tables-beef-magazine.pdf

A Lesson on Bleached Thistles

Another version of this article by Christine Gelley was originally published by The Noble Journal Leader on August 21, 2017.

The 2017-2018 school year has officially begun. Good luck to all the students, parents, teachers, and staff as school goes into full swing again. Please be careful out on the roads as the buses transport our youth safely from point A to B and honor school zones during appropriate hours.

The 2017-2018 school year has officially begun. Good luck to all the students, parents, teachers, and staff as school goes into full swing again. Please be careful out on the roads as the buses transport our youth safely from point A to B and honor school zones during appropriate hours.

I am reminded that even as adults out of school, a day should never pass without us learning something new. It is funny that after you learn something new, it seems to suddenly pop up in various places. That happened to me recently while investigating some bleached Canada thistle.

The photo of the pasture was strange. Across the green leaf canopy there were thistles with white tops. Only the thistles were white and only the top halves of the plants. At first I thought it might be some kind of herbicide injury, but this field had not been sprayed with any herbicides. It wasn’t a fertility issue, because it was only the thistles affected. It seemed so odd and I had never seen this before.

After investigating and sifting through material from Ohio State’s Buckeye Yard and Garden blog, I found the answer from Assistant Professor Joe Boggs, who works out of Hamilton County. Dr. Boggs explained that these symptoms are caused by a bacterial pathogen called Pseudomonas syringae pv. Tagetis. This disease is unique to Canada thistle. It is effective in reducing seed populations and can cause plant death. That sounds like good news for pasture managers.

Although the disease is capable of reducing seed production by up to 87%, Canada thistle produces so much seed that populations continue to be present, even when managing to promote the spread of the bacteria. Unfortunately, the bacterium has not yet been propagated successfully in laboratories. Maybe in the future there will be a breakthrough on how to use this bacterium as a biological control for thistles.

In the meantime, if you want to promote the spread of this disease in your pastures, the easiest way to do so is to mow those white tops off while the canopy is damp. Mow the afflicted area where symptoms are visible first and then proceed to mow the rest of the pasture.

The day I learned about this phenomenon, I saw it in 2 different locations on my drive home. Now that I know what it is, it catches my eye wherever I go.

Tom Bodett once said, “The difference between school and life? In school, you’re taught a lesson and then given a test. In life, you’re given a test that teaches you a lesson.” I think he was absolutely right.

Pasture Recovery Following Flooding

Another version of this article by Christine Gelley was originally published by The Firelands Farmer on July 27, 2017.

Farming in Ohio continues to deliver challenges year after year. Summer 2017 has brought frequent heavy rains and temporary flooding to much of Ohio and beyond. Damage to agricultural land and crops has been noted with corn and bean setbacks drawing the most attention, but pasture damage is prevalent and concerning as well. Remediation of damaged pastures after flooding begins with evaluation.

Many of the forages used in our region are fairly resilient to submersion and waterlogged soils. How resilient they actually are depends on many factors. These include temperature, length of the stress period, depth of the water, growth stage of the plant, and silt deposition. Other associated concerns to be evaluated include stand age, animal activity, potential diseases related to flooding, erosion, and transport of weed seed from one property to another.

Summer floods have the potential to cause more damage to plant tissue than spring floods, because warm temperatures increase the rate of plant damage. The longer the water sits and the deeper it becomes, the greater the chances for plant death. Standing water is more detrimental than flowing water.

The more leaves that reach above the water surface, the better. Erosion will create soil fertility issues and silt deposition may suffocate some plants. Most of our common forages will tolerate 2 inches of deposited silt or less without substantial damage.

How long plants can survive submerged in standing water varies. Actively growing alfalfa will typically recover from 3 days submerged. Phytophthora scouting is important and should be conducted about a month following flooding, with action taken upon detection. Ryegrass and orchardgrass will survive several days submerged and tall fescue will persist even longer.

Legumes tend to be less tolerant of submersion than grasses, but can persist exposed in waterlogged soils for extended periods. Alfalfa can typically survive 1-2 weeks of waterlogged soils, while white clover can tolerate up to three weeks, and red clover up to four weeks.

Water flow patterns can flush soil, weed seeds, manure, and microbes into flooded pastures and cause concerns for animal health. If deposited silt levels are too high, animals may accidently consume substantial amounts while grazing, which can cause digestive issues. Weed seeds can be swept into the pasture and establish themselves in the damaged areas, crowding out the desirable forages during flood recovery.

Detrimental weeds taking over damaged areas will reduce intake of high quality forages and may pose risks if poisonous plants become established. In times of pasture stress, animals are more likely to consume poisonous plants in an effort to find enough to eat. Microbes and parasites are also easily transported into grazing pastures if water flows through an area of manure or sewage storage. It would be best to wait a couple weeks to return animals to pastures that have been flooded with tainted water. This will help maintain good herd health.

To prevent further pasture damage, do not return animals to the pasture and/or use equipment in waterlogged areas until you can travel through the field without compressing the soil. Grasses that form a thick sod will be able to accommodate grazing more quickly than bunch type grasses.

Once the water has drained from the pasture and the soil, investigate if there are any management decisions you could make now to reduce damage if a duplicate flooding event occurred. Consider reseeding heavily damaged areas.

Choose varieties that will withstand the conditions of your operation. Consider planting an annual forage to compensate in such areas as an emergency crop while you plan for the long term. Planting an annual forage will reduce further erosion, provide competition for weeds, and supply feed for animals more quickly than perennials. Annual ryegrass offers excellent tolerance to poorly drained soils, wheat has good tolerance, while oats, rye, and sorghum-sudangrass offer fair tolerance.

When the flood has receded and the sunshine returns, look forward to the future. Remember what you have learned and imagine the possibilities of tomorrow, rather than dwelling on the troubles of yesterday.

Fescue Toxicosis-Knowing the Signs

Another version of this article by Christine Gelley was originally published by Ohio Cattleman on July 17, 2017.

Tall fescue “Kentucky-31” (KY-31) is one of the most predominant forages in the nation. Its popularity began in the 1930s when a wild strain of fescue was discovered on a Kentucky farm and it became recognized for wide adaptability. In the1940s, the cultivated variety was publically released and can now be found in most pastures in the United States. This cultivar is easy to establish, persistent, tolerant of many environmental stresses, resistant to pests, and can aid livestock managers in prolonging the grazing season. However, tall fescue does not accomplish all of these tasks unassisted.

An endophytic fungus called Neotyphodium coenophialum can be credited for many of these benefits. The fungus cannot be seen and can only be detected by laboratory analysis. The fescue endophyte forms a mutually beneficial relationship with the grass, but this symbiotic relationship does not carry over for grazing livestock. It did not take long for tall fescue to develop a reputation for poor animal intake and weight gain. It wasn’t until the late 1970s that these symptoms and others were traced back to the endophyte.

The endophyte produces ergot alkaloids (a type of mycotoxin) that can significantly influence animal performance. When consumed in high concentrations, these mycotoxins cause constriction of the blood vessels. Symptoms can range from mild irritation to tissue death. In severe cases, full constriction can occur resulting in the loss of appendages such as hooves and tails or early abortion in pregnant animals.

Endophyte-free cultivars were developed following this realization, but they struggle to persist year after year in grazing systems. Novel endophyte cultivars have also been developed. These cultivars still contain an endophyte that passes benefits onto the plant, but do not produce harmful side effects in grazing animals. Despite these advances, few beef producers have renovated pastures to replace the population of KY-31 with improved cultivars.

Unless you have done pasture renovation, fescue toxicosis should be on your radar. There are many strategies for reducing the impacts of the endophyte in your herd and they all begin with recognizing the signs of toxicosis. Cattle with dark hair coats may display more intense symptomology. This is due to solar radiation, which can drastically increase body temperature.

The following may be mild symptoms of fescue toxicosis:

- Low feed intakes.

- Low weight gain.

- Rough hair coat/retention of winter coat into warm months.

Moderate symptomology may include:

- Low milk production.

- Reduced reproductive success.

- Increased time spent in shady spots.

- Increased time spent wading in water sources.

- Bovine fat necrosis- the development of hard fat masses. Most commonly in the abdomen, these masses create digestion and birthing difficulties. This is condition is generally associated with fescue pastures that have received heavy nitrogen fertilization.

Signs of severe toxicosis include:

- “Fescue foot”- the loss of hooves or tails due to lack of blood flow to the extremities.

- Loss of pregnancy due to lack of blood flow to the fetus. Early abortion is of greatest concern for pregnant mares in the third trimester of gestation, but can also occur in cattle and sheep.

Pasture renovation with a novel endophyte cultivar is the most effective option for reducing the influence of endophytic fescue, but is not a feasible option for all pasture managers. One of the easiest way to combat the influence of KY-31 is to dilute it with other forages, such as red and white clover. Be sure to manage grazing height to promote legume growth. Another option is to establish an alternate stand of annual forages to utilize for grazing in mid-summer when pasture endophyte concentration is the greatest and symptoms of exposure are most obvious. Because the fungus accumulates in seed heads, harvesting hay before seed heads develop and clipping seed heads from grazed pastures will reduce the endophyte exposure to your herd.

Stockpiled fescue has few endophyte concerns because fungal concentration drops in late fall and winter. Livestock symptoms will also be less intense due to the cooler temperatures. Fescue endophyte can persist for up to two years in stored hay, so animals fed KY-31 hay may benefit from supplementary grain and/or an added ration of legume hay to their winter diets.

The damages of fescue toxicosis often go undetected in beef production and can have drastic influences on animal performance. Being aware of endophyte issues early and implementing good management techniques will go a long way for increasing herd productivity and in turn, profitability.

If you suspect that fescue toxicosis is significantly affecting your beef herd, talk with your veterinarian about reducing cattle stress, reach out to your local Extension personnel, and investigate ways to improve your specific system through pasture and grazing management.

Citations for this article:

- https://guernsey.osu.edu/sites/guernsey/files/imce/Program_Pages/ANR/AgResearch/2002%20Stockpiling%20Tall%20Fescue%20factsheet.pdf

- http://utbeef.com/Content%20Folders/Forages/Fescue%20Toxicity/Publications/sp439a.pdf

Should I add more legumes to my pasture?

Another version of this article by Christine Gelley was originally published by Progressive Forage on March 1, 2017.

At A Glance:

Including legumes in grass pastures has the potential to increase the overall nutritive value of the pasture and decrease the need for supplemental nitrogen fertilizer. Read on to find out if you should add more legumes to your pasture.

What is so special about legumes?

There is something special about legumes that sets them apart from our other forages. They have the ability to foster mutually beneficial relationships with soil bacteria that convert organic nitrogen, which is an unavailable form for plants to utilize, into inorganic nitrogen, making it available for plant uptake. The bacteria benefits from the nutrients in the legumes’ root systems and the legumes benefit from the release of nitrogen from the bacteria.

You may think, “Wow! Free nitrogen! That sounds like a no brainer. Who doesn’t want free nitrogen fertilizer?” Well, it may be a little more complicated than that.

If a surplus of nitrogen is already available in the soil, adding legumes won’t solicit a noticeable result, but if there is a lack of available nitrogen, then a difference may be observed. In other words, if you regularly fertilize your pasture with a source of nitrogen and add legumes, yield may not differ. However, if you never apply nitrogen fertilizer, aside from the manure of grazing animals, you will probably observe a difference after adding inoculated legumes.

Inoculation, why does that matter?

Unless legumes were already widely dispersed in a pasture recently, it is unlikely that the soil bacteria that you need are there to form these mutual relationships. Therefore, the seed you plant needs to be inoculated (treated) with the live bacteria in a stable form. Some legume seed is sold inoculated, but some is not. Which means you will need to inoculate it before planting.

This sounds good. Tell me about nutritive value.

Some common crops that belong to the legume family include: alfalfa, clovers, beans, and peas. The weed that ate the south, kudzu, is also a legume. In general, legume forages have low fiber content and high protein content. Animal intake on legumes in pasture and on hay is higher than on grasses and so is digestibility. With appropriate management this can equate to an increased rate of growth for livestock and the ability to increase or maintain body conditioning scores during crucial times. However, consuming too much legume forage can cause bloat, due to a lack of adequate fiber.

So, how do I know how much I need?

Determining the appropriate proportion of legumes to add to a predominately grass pasture depends on a few factors.

- Do you plan to renovate the pasture or just add to it as it exists?

This will determine how many options you have for seed, your planting methods, and the amount of seed you will need. From here on, I will assume we are adding to pastures as they exist.

- Do you already have some legumes?

If 30% or more of your pasture is already composed of legumes, you probably have enough to work with already. If you have some, but less than you would like, managing grazing or cutting height can help you boost the amount of legumes you see.

Most of the grasses that we use in our forages systems will grow to higher heights than our legumes. If the canopy above the legumes is too thick, sunlight won’t filter down to the legumes and this will lead to reduced growth. Keeping pasture height managed with consideration of both the grasses and legumes, should allow both to thrive if all other factors (soil texture, pH, fertility, soil moisture) are adequate.

- Are you adding annual or perennial legumes?

Annual legumes like crimson clover, soybean, or cowpea will only persist for that growing season. These legumes typically require more soil preparation and have stricter planting guidelines than perennial legumes, but they pair well with annual grasses and work well in rotation with other annual crops.

Perennial legumes like white and red clover, alfalfa, birdsfoot trefoil, sericea lespedeza, and perennial peanut will persist for multiple years and have the potential to spread throughout the pasture by seed, stolons, or rhizomes. Perennial legumes are usually good options for adding legumes to an existing perennial grass pasture. Frost seeding is a popular method of establishment. Seeding rates and planting methods will vary depending on which species and variety you chose.

How do I know what legume will work for me?

Species and variety selection is best determined based on your individualized soil tests, pasture maps, and management plans. Variety trials are conducted across the country each year and results are published in unbiased reports that you can access through your local Extension office, agricultural co-op, seed dealer, and often online from your state’s land-grant university(ies). These reports will help you identify which species and varieties fit your pasture, as well as, provide information on appropriate seeding rates and planting conditions, harvesting techniques, and often forage quality analysis.

If in doubt, please reach out. There are free services available to help you make a decision based on a plan customized for your specific goals. County Extension personnel are one of those services and we are happy to help you along the way.

Summary

The benefits of adding legumes to your grazed pastures or hay fields are numerous, but there are important factors to consider before you plant the seed. Each situation is slightly different. Trial and error is the most effective way to learn what works for you, but you can reduce the amount of error you encounter by being fully acquainted with your pastures and developing production goals for your forage and animals.

Hay Testing for Efficient Winter Feeding

Another version of this article by Christine Gelley was originally published by Farm and Dairy on January 5, 2017.

It’s January in Ohio. Most graziers are probably feeding a good portion of hay as a part of their animals’ daily ration. Even if there is a supply of stockpiled forage available, we tend to make hay available just in case they need a little extra. It is likely that grain is also part of that daily ration. Well, how do you know how much hay, grain, and pasture they need? No one wants to leave their animals hungry. In addition, we don’t want to waste time or money with unnecessary feeding. Figuring out the balance can seem like a guessing game, but a great place to start is with a hay test.

Testing the hay you are feeding is well worth the price of sample analysis. Collecting a sample is not complicated and typically results are available from the lab within two weeks. You can acquire the tools and kits on your own to submit samples, or you can find them at most county Extension offices and often from Soil and Water Conservation Districts. Ag co-ops usually offer sample analysis services as well. Whoever you chose to go through, be sure to select the analysis package that will give you the detailed results you desire. The package that costs the least will probably still leave you guessing. My typical suggestion is to select a test that will give you values for moisture, crude protein (CP), acid detergent fiber (ADF), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), total digestible nutrients (TDN), and Relative Feed Value (RFV). Once you receive the results of your analysis, the challenge of interpreting the values arises. How do you know what values are good or bad?

Your hay test results will list values on a dry matter (DM) and an as-fed basis. Nutrients will appear to be higher for DM basis, because all the remaining water (% moisture) in the hay has been factored out. For CP, values of 8% or greater are desired. For ADF, lower is better. Increased ADF values equal decreased digestibility. Neutral detergent fiber is the amount of total fiber in the sample, which is typically above 60% for grasses and above 45% for legumes. As NDF increases, animal intake generally decreases. For TDN and RFV, the greater the values, the more desirable the forage. These values are useful for comparing your forage to other feeds available on the market. Once you have these values compiled you can start formulating rations based on nutritional values of the hay.

First, consider the needs of your animal. Stage of life, current weight, desired weight, and environmental conditions are all important factors. For the sake of an example, let’s assume we are developing a ration for a growing Angus heifer. Currently, she weighs about 800 lbs. and we want her to gain about 200 lbs. by the end of March. Ideally, we would like her to gain about 2 lbs./day. Now, let’s take a look at a hay test example and assume it is for our hay (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1:

| Sample #: | Field 1 |

| Sample Type | Fescue Hay |

| Moisture (%) | 15.91 |

| Dry Matter (%) | 84.09 |

| Crude Protein (DM%) | 12.53 |

| Fiber ADF (DM%) | 37.79 |

| Fiber NDF (DM%) | 72.03 |

| Total Digestible Nutrients | 59 |

| Relative Feed Value | 77 |

According to the information from our hay sample and the recommendations from the National Research Council for beef cows, we could expect this animal to eat about 21 lbs. of hay daily and gain 1.75 lb./day, coming in just short of our goal. This hay should be adequate for meeting the heifer’s energy needs as her main feedstuff. If we think it is worth the investment, supplementing with some high energy, high protein grain could help reach our desired average daily gain (ADG).

Soybean meal has an average of about 44% CP. Supplementing 1-2 lbs. of soybean meal (a pelleted form will increase animal intake) should provide the additional nutrition to reach our goal. Whole shell corn is about 9% CP, which is lower than the CP content of our hay. Unless we are concerned about our hay supply, supplementing corn may not be significantly beneficial.

This was just one example of how a hay test can help with the development of livestock rations. Recommendations will vary depending on types of hay, time of year, animal species, stage of life, and production goals. With so much possible variation, every little bit of knowledge we can secure is helpful for developing production goals and expectations.

Hay tests may not reveal ideal results and they can vary drastically between cuttings. That is the reality of attempting to manage nature. We can rarely do anything under ideal circumstances, but we do the best we can. As you look ahead to the next growing season and putting up hay once again, do everything you can to efficiently improve forage quality and nutritive value of your stored resources. The better the nutritive value of your forage, the less you will need to supplement and the more money you can keep in your pocket. Testing and formulating rations takes some effort, but once it becomes routine it will come with greater ease.

With that, I will leave you with a quote from Jim Rohn, “Success is neither magical nor mysterious. Success is the natural consequence of consistently applying the basic fundamentals.”

Does crabgrass really hate you?

This article first appeared in the Ohio Cattleman Magazine Summer 2016 edition.

You may have heard the rumor that crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis) hates you. Those who profit from the sale of lawn care products may like you to believe that, but despite the claims, it really isn’t true. Each year crabgrass works toward accomplishing the goal of all living things, to reproduce, and if it had a life motto it might be something like: “Life is short, so live it!” Any plant out of place can be considered a weed and in the eye of many, crabgrass fits this description. However in a forage system, crabgrass can be the right plant, in the right place, at the right time.

Crabgrass is an annual warm-season grass that reproduces by seed and completes it’s lifecycle in a timeframe offset from that of commonly used cool-season grasses like tall fescue, orchardgrass, and ryegrass. It begins germinating when soil temperatures reach 58°F and can thrive while other species lay dormant in the summer heat. It has few known pests and pathogens and can grow well on marginal sites. Intentionally utilizing crabgrass as forage could lead to opportunities for extending the grazing season and producing high quality hay during the warmest periods of Ohio summers.

In 1849 crabgrass was introduced by the U.S. government for use as forage and has since spread across the nation. The Noble Foundation has been conducting research on crabgrass as forage in Ardmore, Oklahoma since the 1970s. In the 1980s the Noble Foundation released the first cultivated crabgrass variety, ‘Red River’, later followed by the variety, ‘Quick N’ Big’.

Universities and producers have also experimented with these varieties and have found that they produce forage of excellent nutritive value with high intake and rate of gain by livestock, particularly beef cattle. Under good growing conditions and management to reduce seed head development, values of up to 15% crude protein (CP) and averages of 10% CP from June through September have been observed for crabgrass ‘Quick N’ Big’. Rotational grazing has proven more efficient for dry matter production and animal gains than continuous grazing. If managed for hay, crabgrass should yield at least two substantial harvests per year. Care should be taken to keep crabgrass vegetative during production through removal of seed heads, thereby preserving good nutritive value throughout the summer.

Well drained soil is best for crabgrass. It is tolerant of soils with 5.5-7.5 pH. Seed should be broadcast on a tilled soil surface or drilled at ¼ inch at a rate of 3-5 pounds of pure live seed per acre and cultipacked. If crabgrass has established well and is allowed to reseed for the next season, lower seeding rates may be effective in subsequent years. With adequate moisture, seeds will germinate in a few days and be ready for grazing in about 30 days. Crabgrass is highly responsive to nitrogen, so split applications can generously increase dry matter yields. Defoliation heights can be tolerated to as low as 3 inches, stands can be ready to graze at 6 inches, and cutting for hay should occur during early boot or about 18 inches high. Crabgrass hay may take longer to cure than other popular forages. Dry matter yield typically ranges from 2-5 tons/acre. It can be incorporated in crop rotations with other annual crops, used as an emergency forage, or allowed to intermix with other forage species. It is unlikely that you will find crabgrass seed on the shelves of your local Ohio seed dealer, but it can be ordered from the supplier and variety developer, R.L. Dalrymple of Oklahoma.

Your neighbors may think you are crazy if you decide to grow crabgrass on purpose, but in truth it would be crazy to pass up the opportunity to boost forage production, animal gains, and profitability. So while your neighbor tends to the pursuit of the perfect lawn, you can tend to the pursuit of perfect forage for your cattle, which may include the undue black sheep of forage, crabgrass.