First Ladies and the Gowns They Wore

by Kerry Ulm

In the Historic Costume & Textiles Collection’s (HCTC) storage rooms in Campbell Hall, all garments are cared for equally. Some more fragile pieces are set apart and laid in drawers, but most are hung beside each other, lined up according to decade.

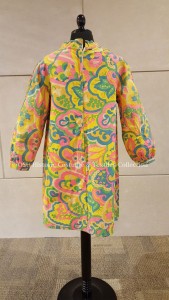

Peek into the drawers and the sections for the 1920s, 1960s, and the 1980s, however, and you’ll find four gowns in particular. One is covered in heavy beads, another with cream-colored flowers. A third is marked by vertical stripes, and a fourth has a fabulous blue skirt.

Four different designers created these dresses. They were worn by different women, and given to the collection by different donors. Yet, they all have something in common. Each has a connection to a former First Lady of the United States.

Over the years, the office of the First Lady has been developed and changed by the women who have occupied it. Just as their politician husbands have had to keep an eye on their own appearance and mannerisms for the sake of swaying voters, so, too, the First Ladies have become known for the clothes that they wore. For some, fashion was personally important, for others, not as much, but in all cases, what they wore reflected the era in which they lived in the White House. Interpreting these eras were the designers behind their most notable gowns and outfits. Together, First Ladies and the designers they grew close to, created iconic views of history through fashion.

Florence Harding

The oldest of these First Lady gowns belonged to Florence Harding and dates from 1922 or 1923. It is more frail than the others and weighed down by heavy beading. When it is not being displayed, the gown is stored horizontally, resting on a long, wide sling of fabric inside of a drawer. Unlike the other gowns, the designer of this one is unknown. Mrs Harding was in the White House before the significance of the designer/First Lady relationship came about.

What it lacks in designer identification, the Harding dress makes up for with weathered personality. Little clues from its long life point to its wearers’ activities. Several dark, red-brown stains—the sort that could have came from dribbles at a White House dinner—stand out on the front against the green-blue fabric. They’re camouflaged by the dark beading, which, at several points, has replacement beads that flare in brighter colors.

Florence came to the White House in 1921 when her husband, Warren G. Harding, took office after Woodrow Wilson. After a post-WWI recession, the Harding presidency began to see the upsurge of the Roaring Twenties. As First Lady, Florence reopened the White House to the public, regularly hosting garden parties for veterans and poker parties in the library (complete with illegal liquor!) This gown was likely worn to these events. But, her stay in the White House was short. President Harding died in office in August of 1923 and Florence passed away just over a year later in November of 1924.

However short their time together in the White House, its doubtful Harding would have made it there at all given today’s climate of extremely close scrutiny of presidential candidates and their, as well as their family’s, personal lives. Florence and Warren each had their own less-than-spotless reputations back in their native Marion, Ohio.

When she was 19, Florence quit school at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music after one year to elope with her first husband, Henry DeWolfe. They separated soon after but had a son together, Eugene, who was raised by his grandfather.

At the start of her second marriage, Florence was again gossip fodder. When she and Warren married quite legally and respectably in 1891, the masses of Marion were whispering about how the bride was shockingly five years older than the groom.

The groom himself went on to create his own drama. Warren is known to have had at least two extramarital affairs, one with Carrie Fulton Phillips, the wife of a friend, and the other with Nan Britton, the daughter of a friend. In recent years, DNA testing has proven that Harding fathered Nan’s daughter.

Given these factors, it’s no surprise that the Hardings weren’t known to be a particularly affectionate couple. What they lacked in tenderness, though, the pair made up for in teamwork.

Florence was a fierce force behind her husband’s success. She began developing this strength by first looking after herself. After her failed marriage to DeWolfe, Florence supported herself financially by using the skills she learned during her time at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music to teach piano lessons to Marion residents. Warren had acquired many leadership positions in Marion on his own, and with Florence he was even more successful. Armed with both a strong will and a shrewd business aptitude, Florence oversaw the local newspaper he owned, The Daily Star. Eventually she exercised these talents on a national scale, helping push him along to the White House.

Florence only owned this gown for a year or two before she passed away. It then entered an unknown route of ownership. Likely it was handed around for several decades before eventually coming into the possession of its only other known owner, Madge Cooper Guthery, another famed resident of Marion.

Born in 1910, fifty years after Florence Harding, Madge Cooper Guthery may not have held the national fame that Florence did, but she did hold her own on the local scale. Guthery was an esteemed radio host who, by the time she passed away at 99-years-old in 2009, had come to be known as “the First Lady of Radio.”

She attended Ohio State, graduating with degrees in English and Biology. Her true passion was writing, and while in school, she filled her elective slots with writing courses. After teaching for several years, she took a job in 1941 at a local radio station. At the time, Guthery had become interested in the position because she saw it as an opportunity to learn more about writing. It ended up being the start of a fifty-year career in Marion radio.

As a radio host, she was one of few women in the medium. Throughout her life, she remained passionate about education and in her later years, she both learned and supported learning. She continued her own education hands-on as a world-traveler, and she supported the education of others through various philanthropic means, including supporting her alma mater, The Ohio State University.

Sources:

Florence Harding

Black, Allida. “Florence Kling Harding.” The White House. Accessed July 26, 2016. https://www.whitehouse.gov/1600/first-ladies/florenceharding

“First Lady Biography: Florence Harding.” National First Ladies’ Library. Accessed July 26, 2016. http://www.firstladies.org/biographies/firstladies.aspx?biography=30

“Florence Harding.” The White House Historical Association. Accessed July 26, 2016. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/bios/florence-harding

“Madge Lily Guthery.” The Columbus Dispatch Obituaries. Accessed July 26, 2016. http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/dispatch/obituary.aspx?pid=136060675

Nasaw, David. “Worst Lady: The Wife of Warren Harding May Have Been the First Lady of Deceit.” The New York Times Books. Last modified August 2, 1998. Accessed July 26, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/books/98/08/02/reviews/980802.02nasawt.html

Pierce, Bess, David Collins and Rich J. Johnson. Moline: City of Mills (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 1998), vii.

Scott Spears. “Scott Spears interviewing Madge Copper Guthery (7/16/2006).” Accessed July 1, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I1mr7Cs2X7k

“Warren G. Harding (1865 – 1923).” The Miller Center at the University of Virginia. Accessed July 26, 2016. http://millercenter.org/president/harding