In honor of the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s passing on July 18, 1817, the Historic Costume & Textiles Collection installed three dresses in the Thompson Library Special Collections area. Jane Austen lived from 1775 to 1817, a period marked by significant developments in politics, manufacturing and society as a whole. There was a growing interest in ancient Greek culture and ideals of democracy as opposed to monarchy due to the discovery of Herculaneum and Pompeii in the mid-18th century. This, along with the American and French Revolutions, inspired a change in fashion that reflected these new democratic ideals. Women’s dresses transitioned from the stiff artificial silhouettes popular in the French court of Louis XVI, to the light columnar silhouettes of the early 18th century. This style of gown has come to be known as the Empire silhouette, in reference to the French empire and Josephine Bonaparte who popularized this new style. Women’s gowns were primarily made of white cotton or small floral printed cottons. It was believed that the Ancient Greeks wore only white as the statues that had been discovered were white. The statues were white, of course, due to being bleached by the sun over time, but fashion is frequently inspired by idealism rather than realism so the trend for light-colored gowns continued.

Films of Jane Austen’s novels are often the entry point by which people encounter this period of fashion. Interestingly, most film adaptations dress the actors in fashions indicative of the various novel’s dates of publication rather than when the novels were originally written. For example, Pride & Prejudice was published in 1813 but Jane originally began work on the novel in 1796. Additionally, a close analysis of Pride & Prejudice reveals that the events of the novel were more than likely written to have taken place between 1793 and 1795. The 1790’s were a unique period of transition in fashion and it is much easier for a costume designer to create costumes that reflect the latter half of Jane Austen’s life. In fact, the Empire style of gown is now so intrinsically linked with Jane Austen’s characters in the public’s mind that it is almost impossible to separate the two. Three dresses dating from the time of Jane Austen’s life are on display in the Thompson Library and have been paired with first editions of her novels. Jane died on July 18, 1817 and this year marks the 200th anniversary of her passing. This exhibit invites viewers to celebrate one of Britain’s most popular authors whose novels continue to find a fresh set of devotees with each new generation.

“To be in company, nicely dressed herself and seeing others nicely dressed, to sit and smile and look pretty, and say nothing, was enough for the happiness of the present hour.”

~Emma, 1816

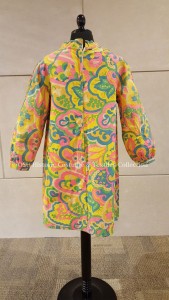

Silk Day Dress

1797-1810

Historic Costume & Textiles Collection

Gift of Friends of the Historic Costume & Textiles Collection

This silk day dress is made from a heavier, stiffer silk that was more common in women’s fashion during the 18th century, but still reflects the new columnar silhouette that had become popular in the late 1790’s. While cotton had become more popular for daywear during this period, wealthier women would still have day dresses made in silk. The character of Emma is one of Jane Austen’s only protagonists that does not have to worry about money. Emma is the only child of a wealthy father and fails to understand, at several points throughout the novel, that financial limitations greatly influence the decisions of those around her.

Austen herself could be described as a member of the “pseudo-gentry”. This class of Georgian society was made up of individuals and families that did not own land but were still gentility “of a sort.” Jane’s father, George Austen, made £1,000 per year at the height of his prosperity, but with a family of eight children this was not a large sum. £500 annually was about the limit at which a family could aspire to gentility. This is the exact sum that the Dashwood women would be forced to live on in Sense and Sensibility. Jane Austen, along with her mother and sister, would find herself in a similar situation after the death of her father in 1805. These three women had to subsist on slightly less than £500. The women were not firmly settled into a permanent location until 1809 when they moved to Chawton House in Hampshire. It was here that Jane was able to settle into a regular routine and devote more time to writing. Between 1811 and her death in 1817, Jane would compose Emma and Persuasion, as well as publish Pride & Prejudice, Mansfield Park and Emma.

“It would be mortifying to the feelings of many ladies, could they be made to understand how little the heart of man is affected by what is costly or new in their attire; how little it is biased by the texture of their muslin, and how unsusceptible of peculiar tenderness towards the spotted, the sprigged, the mull, or the jackonet. Woman is fine for her own satisfaction alone. No man will admire her the more, no woman will like her the better for it. Neatness and fashion are enough for the former, and a something of shabbiness or impropriety will be most endearing to the latter.”

Cotton Day Dress

1800-1810

Historic Costume & Textiles Collection

Gift of Friends of the Historic Costume & Textiles Collection

~Northanger Abbey, 1818

Fashion styles changed rather drastically at the end of the 18th century. The highly artificial and opulent dress of the court of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette transitioned to that of the Greek-inspired silhouette featured in the day dress displayed here. Unlike its predecessors, this new style of dress falls straight and flat to the floor in front, with fullness being concentrated at the center back. Day dresses were commonly made of very fine cotton muslin. While a simple, plain white was popular, floral patterned or “sprigged” muslins were equally popular. The proliferation of cotton gowns was owed in part to the success of the British East India Company which exported large amounts of cotton to British textile manufacturers.

Jane Austen, having been born in 1775, came of age when this revolution in fashion was taking place. While, she does not go into great detail when describing the clothes of her characters, her humor and wit is often on display when fashion becomes a topic of conversation. One such example is featured here. The above quotation is an aside from Jane when describing Catherine Morland’s anxiety as she tries to decide which gown to wear to a ball later in the evening. Northanger Abbey was itself a satire of the Gothic novel and so it should come as no surprise that various aspects of society are satirized within its pages.

“Now I must look at you, Fanny,” said Edmund, with the kind smile of an affectionate brother, “and tell you how I like you; and as well as I can judge by this light, you look very nicely indeed. What have you got on?”

“The new dress that my uncle was so good as to give me on my cousin’s marriage. I hope it is not too fine; but I thought I ought to wear it as soon as I could, and that I might not have such another opportunity all the winter. I hope you do not think me too fine.” [Fanny]

“A woman can never be too fine while she is all in white. No, I see no finery about you; nothing but what is perfectly proper. Your gown seems very pretty. I like these glossy spots. Has not Miss Crawford a gown something the same?” [Edmund]

~Mansfield Park, 1814

Silk Evening Dress

1817-1820

Historic Costume & Textiles Collection

Gift of the Friends of the Historic Costume & Textiles Collection

Evening gowns such as this would be quite like the one that was worn by Fanny Price to formal dinners or balls in Mansfield Park. For the greater part of Jane Austen’s life, evening dresses were the same tubular silhouette as dresses meant for more informal daywear, the difference being they were made of silk and could have more elaborate trimmings. Neither day nor evening dresses had trains, apart from court gowns, from about 1808 onward. This dress has design elements that put it closer to 1820 than 1810 such as its use of a band at the waist. The decoration in its short puffed sleeves mimic slashing, a design element common in garments from the Medieval period. This movement towards medieval revival would expand and continue as fashions begin to change once again in the beginning of the 1820s.

Jane Austen chose to publish her novels anonymously. The author for each book published during her lifetime was simply noted as “A Lady.” It would not be until the posthumous joint publication of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion as a four volume set, that the true identity of this “Lady” would be revealed. Northanger Abbey was actually the first manuscript that Austen sold to a publisher. She sold it under the original title, Susan, to London bookseller, Crosby & Co., for £10. Unfortunately, they decided against publishing. Henry Austen, Jane’s brother, bought the manuscript back from the publisher in 1816. Jane revised it, renaming it Catherine, with the intention of publication but passed away in 1817. Henry Austen renamed it Northanger Abbey and arranged for its publication, along with Persuasion, and penned an introduction which publicly identified Jane Austen as the author of this and previous works for the first time. A first edition of this four volume set is displayed here alongside a first edition of Mansfield Park, published May 1814, and Emma, published December 1815. While Austen’s books went out of print for a short period of time after her death they have rarely been unavailable since.