Hello everyone!

Things have been very busy in the lab over the last few months so below are several of the updates.

Specialist Bee Sampling:

Amber is working on getting specimens turned in for the 2023 season. Thank you to everyone who participated!

Interim reports for 2021 and 2022 sampling are going out now.

Final Reports for the 2020 Bee Bowl Survey:

We finally have the bowl survey specimens identified as low as they are going to go. Individual site level reports have all been sent out. If you did not receive your 2020 bowl report, please let me know.

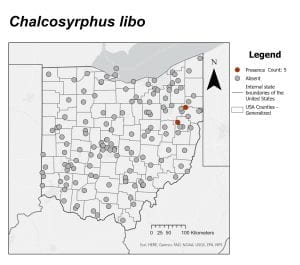

We created a document for each of the species found that includes maps and natural history information. See: AppendixA_BeeBowlMaps_SpeciesProfiles

Presentations:

Undergraduate student Keri Bowyer did a poster comparing bowl traps to malaise traps set in Allen county. She presented her work at the Fall Undergraduate Research Forum. Her poster can be found here: Comparing richness and abundance of beneficial insect taxa 2023 FINAL

New graduate student Matthew Semler did a poster on specialist bee use of thistle at the Ohio Invasive Plants Conference. That poster can be found here: OIPC_Poster_2023_Final

Dr. Karen Goodell, Amber Fredenburg, and new graduate student Lizzy Sakulich presented their work at the national entomology meeting earlier this month. Both Amber and Lizzy took home awards in the judged graduate student presentations. Dr. Goodell recorded her presentation, which can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k0Ap3nOpwvI

Dr. Goodell (left) and Amber (right) met up with Sam Droege (center) since the conference was in Maryland.

Cheyenne Helton has finished up her thesis on bumble bees and floral use. She defended at the beginning of the month. Great work Cheyenne! You can watch a recorded version of her defense by clicking here.

Cheyenne and Dr. Goodell on Defense Day

In summary, the lab has been very busy and productive these last few months!

Photography:

Before turning in the bowl specimens into the museum for archival, I have been working on focus stacking images so we have at least one photo per species. I have made it through everything except the Halictids. Below are some of the example images. Those who are photographers know just how hard it is to get clear shots of things smaller than a grain of rice.

Osmia texana viewed from the side showing the black scopa.

A bumble bee look alike, we got a few Anthophora specimens in our bowls.

Identifying older specimens:

MaLisa has been spending most of her time identifying older specimens. I’ve made a lot of progress on bees from several mines in southeastern Ohio, which has yielded some interesting bees. These are bees from older projects that have needed attention for almost a decade, so it has been exciting to make some progress on those specimens.

Best wishes,

MaLisa

The pitting on the male Andrena quintilis

The pitting on the male Andrena quintilis