When you think of Appalachian stereotypes in the media, it’s not surprising that those outside the region may point to images of boarded-up store fronts, aerial views of dented mobile homes, and rusty automobiles. Last year, The Guardian published a four-part series, America’s poorest white town: abandoned by coal, swallowed by drugs, one of which focuses on high rates of obesity, drug addiction, and post-coal economic devastation in Beattyville, Kentucky. Area spotlights like these often do so with the goal of shedding light on economically-depressed areas in order to leverage resources for these communities. However, what toll does it take on a community when the national spotlight portrays it as damaged? It’s not news to me that my hometown faces economic challenges or that my community is struggling with the grip of opiates on our loved ones, but that isn’t all that comes to mind when I think of home.

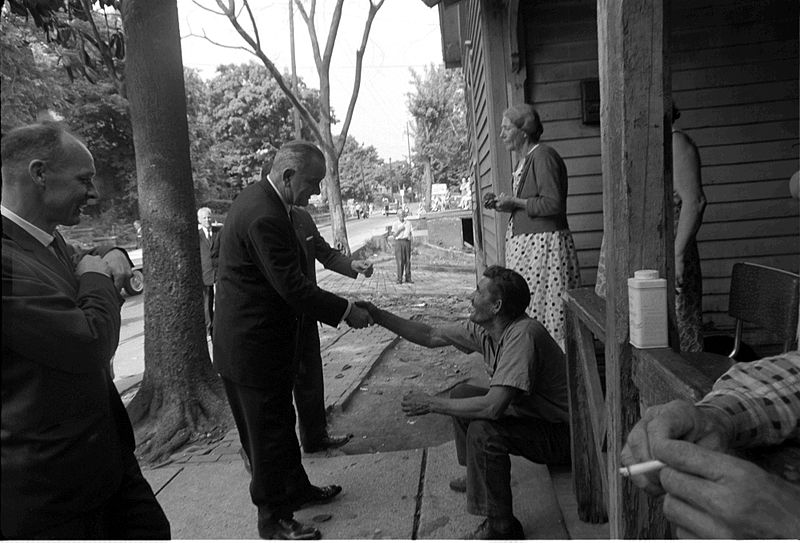

For Appalachian communities, we’re no stranger to these stereotypes of poverty in the media beginning with the hordes of journalists that flooded the hollers of Eastern Kentucky in 1964 when President Johnson used the region as a high profile symbol to gain support for his War on Poverty. Images of rickety shacks, coal-dust covered faces of miners, and barely-dressed children flashed on television screens across America.

What does it mean when our communities have no control over how our stories are told and what images are used to convey them?

In 2009, Eve Tuck, Assistant Professor of Educational Studies at State University of New York published an open letter for communities, researchers and educators to consider long-term results of “damage-centered” research. Speaking of her own Native community in Alaska, she explores the effects on a people when we begin to “think of ourselves as broken”. She takes on the ethics of research and cautions those who do work in disenfranchised communities to reconsider the effect their roles have on these groups. (Tuck, p.422). Referencing communities of color, indigenous people, and those living in poverty, she distinguishes that while research may addresses the social and historical factors that shaped this disparity, without the context of colonization and racism at the forefront, “all we’re left with is the damage”. Tuck suggests that through a framework of desire, communities can recognize our sovereignty and cultivate the vision and wisdom of our communities for a collective movement forward implying damage-centered research stalls progress (Tuck, p. 417)

Rewriting the narrative about Appalachia is not an easy job. We must rethink our roles in research especially when we grapple with the insider/outsider effect and attempt to find solutions for it. We must ask what steps can we can take to ensure a mutually-beneficial goal for both the research and the community it hopes to serve? How can we better work with experts from within the communities to shape the questions we ask? What effects will the data have on our subjects?

But part of rewriting the narrative is letting our communities speak for themselves. We must support the work of people like Roger May, a native of West Virginia, whose work Looking at Appalachia focuses on redefining the images of the region. He accepts submissions from people in the Appalachian region and collectively exhibits these works to portray, more accurately, the cultural richness and complexity that can be found in our home counties.

Tuck’s letter was especially empowering for me to reiterate the importance of increased involvement of Appalachian students and faculty in higher education including leading those research efforts in our own communities. Our complex lives are ones of both damage and desire and who better to tell the story than those of us who have climbed these hills?

Brien Vincent. 6/18/2014. Rural Action Watershed Restoration AmeriCorps member Rand Romas leads a pond study as part of the KEEN summer camp at Lake Hope State Park near McArthur in Vinton County, Ohio.

Lynaya Elliott is Department Manager for the Department of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies. She also serves as one of the program leaders for the Community of Appalachian Student Leaders and a co-facilitator for The Appalachian Project.

References

Tuck, Eve. “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities.” Harvard Educational Review 79.3 (2009): 409-427.

McGreal, Chris. “America’s Poorest White Town: abandoned by coal, swallowed by drugs.” theguardian.com Guardian US, 12 November 2015. 20 December 2015.