by Theresa Ferrari, Extension Specialist, 4-H Youth Development

by Theresa Ferrari, Extension Specialist, 4-H Youth Development

Sodium, generally in the form of salt, is a mineral that is regularly added to foods for flavoring and preservation. It is a necessary mineral for the human body, so you do need some sodium (a very small amount) in your diet. Your nervous and cardiovascular systems cannot operate properly without it. However, the average American gets too much sodium. Too much sodium increases a person’s risk for high blood pressure, which can lead to heart disease and stroke. Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S.

High blood pressure and stroke may seem a long way off for teens. However, many young people are already consuming large amounts of sodium. According to the American Heart Association, children with high-sodium diets are almost 40% more likely to have elevated blood pressure than those with lower-sodium diets. About 1 in 7 youth aged 12 to 19 years old had high blood pressure (hypertension) or raised blood pressure. Youth with high blood pressure are more likely to have high blood pressure when they are adults. Raised blood pressure is a major cause of heart disease. Therefore, eating a diet lower in sodium can help lower blood pressure, and thus may prevent heart disease later in life.

Some sodium is necessary because it has many important jobs — sending nerve signals throughout the body, tightening and relaxing muscles, and maintaining proper fluid balance. The kidneys regulate the body’s sodium level by getting rid of any excess. But if there’s too much sodium in the blood, the kidneys can’t keep up. Excess sodium in the blood pulls out water from the cells; as this fluid increases, so does the volume of blood. That means more work for the heart just to do its everyday job of pumping blood, which increases pressure in the blood vessels. Over time, this extra work takes it toll, and a person’s chances of suffering from heart disease goes up.

How much is enough? The 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend Americans ages 14 years old and older eat no more than 2,300 milligrams (mg) of sodium a day. For comparison, 2,300 mg is the amount in about a teaspoon of salt. Lower consumption — no more than 1,500 mg per day, about two-thirds of a teaspoon of salt — is recommended for younger children, middle-aged and older adults, African Americans, and people with high blood pressure. With most Americans getting much more than they need — 3,400 mg of sodium per day, on average – it easy to see that there is room for improvement in the American diet.

|

Sodium by the Numbers |

|

| 1,500 mg | Recommended limit for young children, middle-aged and older adults, African Americans, and people with high blood pressure |

| 2,300 mg | Recommended limit for Americans ages 14 years old and older |

| 3,400 mg | What most Americans get in their diet |

Sources of Sodium

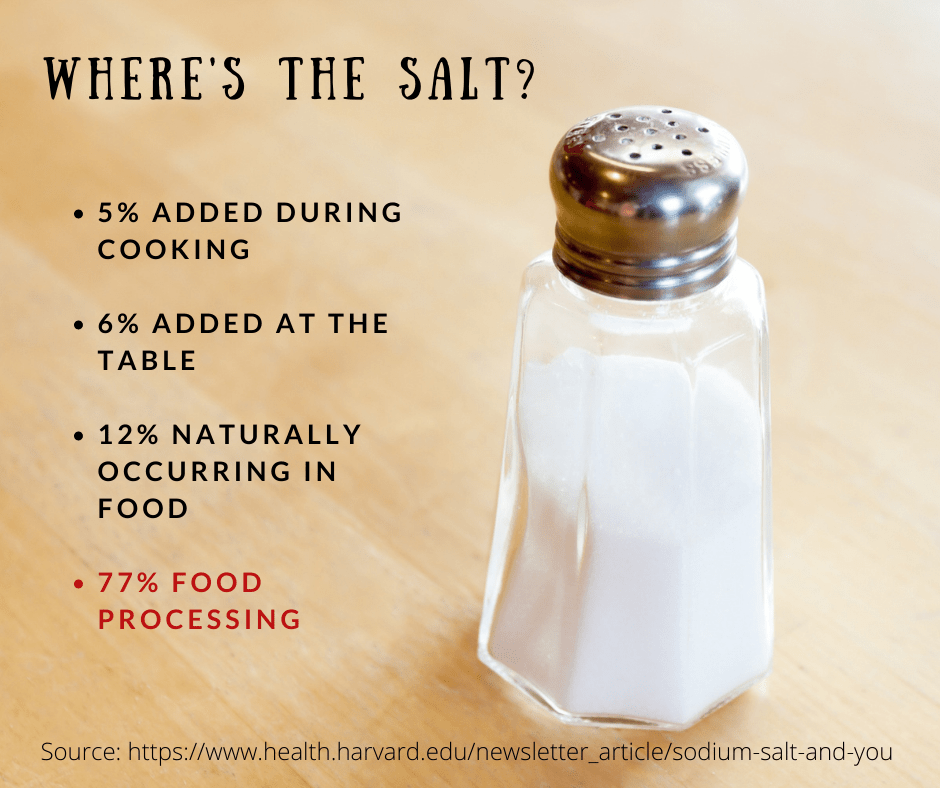

Most of the sodium in our diet comes from salt. The words “salt” and “sodium” are often used interchangeably, but they don’t mean the same thing. The chemical name for salt is sodium chloride; salt is 40% sodium and 60% chloride; therefore 1 teaspoon of salt is equivalent to 2,300 mg of sodium.

Salt is the source of about 90% of sodium in the diet. But most salt doesn’t come from adding salt during cooking or at the table — it comes from processed foods and restaurant meals.

According to national data about Americans’ eating habits, these foods are the leading contributors to the sodium young people eat:

- pizza

- breads and rolls

- processed meats (such as bacon, sausage, cold cuts, and hot dogs)

- savory snacks (such as chips and pretzels)

- sandwiches (including burgers)

- chicken patties, nuggets, and tenders

- pasta mixed dishes (like spaghetti with sauce)

- Mexican dishes (like burritos and tacos)

- cheese

Did any of these foods surprise you? Sometimes it’s easy to tell when foods taste salty. But other higher sodium foods are deceptive, such as bread, because they don’t taste salty. Then there’s my snack of salted mixed nuts: they taste salty, but with 120 mg per 1/4 cup serving, they have just 5% of the daily value for sodium. These examples mean that you have to pay special attention to sodium content when shopping and eating out.

The sodium content can be found on the Nutrition Facts label. You can find the percentage of daily value (% DV) on the label, or by dividing the amount of sodium in a serving by 2,300 mg. As a general guide:

Sodium Scavenger Hunt

Do you know the amount of sodium in your diet? Time to go on a scavenger hunt in your cupboards and refrigerator to locate sources of sodium. Collect at least five or six different foods, and try to get different types of foods. If you want to include a food that doesn’t have a food label (such as fresh fruit or vegetables), you can find expanded nutrient profiles in FoodData Central of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Download the Sodium Scavenger Hunt, and then use the information from the labels to complete this activity.

Here is an example:

|

Food Item |

Serving Size |

Sodium Content (per serving) |

Sodium Level %DV |

Sodium Swap |

| Carrots, fresh | 3 oz | 65 mg | 3% | Low sodium food – no swap needed |

| Tuscan-Style chicken & white bean soup |

1 container (15.5 oz) |

1,420 mg |

62% |

Lower-sodium soup

Homemade soup using no-salt added beans |

What conclusions can you draw from your table? Were you able to come up with sodium swaps?

Today’s Takeaway: Sodium is a necessary nutrient, but most Americans consume more than is recommended. Now that you know the dietary recommendation for sodium, look for our follow-up post on more sodium swaps and ways to reduce sodium in your diet.

Subscribe: Don’t miss out on our health living posts. You can subscribe by clicking on the “Subscribe” button in the lower right corner of your screen. You can also check out all the other Grab and Go Resources.

Adapted from:

American Heart Association. (2018). Sodium and kids. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sodium/sodium-and-kids

Frank, A. P., & Clegg, D. J. (2016). Dietary guidelines for Americans—Eat less salt (JAMA Patient Page). Journal of the American Medical Association, 316(7), 782. https://doi.org10.1001/jama2016.0970

Harvard Health Publishing. (2009). Sodium, salt, and you. Harvard Medical School. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/sodium-salt-and-you

Harvard Health Publishing. (2014). How to stay in the sodium safe zone. Harvard Medical School. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/how-to-stay-in-the-sodium-safe-zone

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Sodium in your diet. https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-education-resources-materials/sodium-your-diet

Additional References

American Heart Association. (2016). Why so many African-Americans have high blood pressure. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/why-high-blood-pressure-is-a-silent-killer/high-blood-pressure-and-african-americans

Arbuto, N. J., Zoilkovska, A., Hooper, L., Elliott, P., Cappuccio, F. P., & Meerpohl, J. J. (2013). Effect of lower sodium intake on health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 346, f1326. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f1326

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Leading causes of death. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

Hardy, S. T., & Urbina, E. M. (2021). Blood pressure in childhood and adolescence. American Journal of Hypertension, 34(3), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/phab004

Jackson, S. L., Zhang, Z., Wiltz, J. L., Loustalot, F., Ritchey, M. D., Goodman, A. B., & Yang, Q. (2018). Hypertension among youths — United States, 2001–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 758–762. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6727a2

Leyvraz, M., Chatelan, A., da Costa, B. R., Taffé, P., Paradis, G., Bovet, P., Bochud, M., & Chiolero, A. (2018). Sodium intake and blood pressure in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental and observational studies. International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(6), 1786–1810. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy121

Kit, B. K., Kuklina, E., Carroll, M. D., Ostchega, Y., Freedman, D. S., & Ogden, C. L. (2015). Prevalence of and trends in dyslipidemia and blood pressure among US children and adolescents, 1999-2012. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(3), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3216

Rios-Leyvraz, M., Bovert, P., & Chiolero, A. (2020). Estimating the effect of a reduction of sodium intake in childhood on cardiovascular diseases in later life. Journal of Human Hypertension, 34, 335–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-01800137-z

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/resources/2020-2025-dietary-guidelines-online-materials