We’ve been receiving quite a few questions about bacterial spot of peppers during the past few weeks. This is not the best time to start thinking about managing bacterial spot (caused by Xanthomomas euvesicatoria and a few other Xanthomonas species), since like other diseases caused by bacteria, once an epidemic gets underway in the field there is not much that can be done about it. Symptoms may abate in dry weather, but in much of Ohio we have had plenty of rain to sustain bacterial spot epidemics. So the following is mostly about prevention for next season, and includes some photos to help in identification. Of the three leaf spotting bacterial diseases of peppers (spot, “speck”, and canker), bacterial spot is the most serious. Bacterial “speck” symptoms on pepper leaves are indistinguishable from those of bacterial spot, and we have not seen speck symptoms on fruit. Bacterial canker is quite easy to differentiation from bacterial spot (see photos at the end of this entry). It is important to know which disease is present, and also to differentiate bacterial diseases from those caused by other pathogens, or by environmental or other causes. We don’t see too many fungal leaf spotting diseases of peppers in Ohio, but fungicides can be helpful in managing them if necessary.

Managing bacterial spot requires an integrated strategy composed of the following elements: 1) pathogen-free seeds, 2) resistant varieties, 3) pathogen-free transplants, 4) proper crop rotation/site selection, 5) cultural management in the field and 6) bactericides.

1) Start with “clean” seed. The earlier bacterial spot appears in the pepper crop production cycle, the more serious the disease may be. The first step in prevention of the disease is to exclude the pathogen from the crop. Since this disease is seedborne, and it is often introduced in seeds, obtaining clean (pathogen-free) seeds should be a first priority. If seeds are purchased, they should be obtained from a reputable producer with a good track record for selling high quality seed. Ideally, the producer will have tested a sample of the seeds for the presence or absence of the bacterial leaf spot pathogen. Always ask if the seeds have been tested. If they have been tested and the results are negative, there is a relatively low risk that the pathogen may be present. If they have not been tested, seeds should be treated with chlorine bleach to kill any bacteria on the surface. If seeds are saved from the previous year’s crop or obtained from a source with an unknown track record, they should always be treated. Organic growers may prefer a hot water treatment to sanitize seeds.

2) Choose a resistant variety. There are numerous varieties of bell and other peppers that are resistant to the common races of the bacterial leaf spot pathogen. Seed companies provide information on resistance to bacterial spot. There are many variants of the bacterial spot pathogen, called races, that may react differently depending on the resistance genes present in the variety. Although races are known that can cause disease on some resistant varieties, in general the varieties advertised as resistant have been performing well in Ohio. However, resistance to bacterial spot does not apply to speck or canker. If a variety advertised as resistant to bacterial spot develops spot-like symptoms, a sample should be sent to the OSU Vegetable Pathology Lab in Wooster for diagnosis. Vegetable diagnostic services are supported by OSU and the Ohio Vegetable and Small Fruit Research and Development Program and there is no fee for Ohio vegetable growers. Resistant varieties should never be the sole means of disease management, no matter how tempting it may be to rely on this management strategy.

3) Use pathogen-free transplants. There is very little direct seeding of peppers, as growers have seen the many advantages of transplanting seedlings instead. However, the introduction of this phase (transplant production) to the pepper cropping cycle has led to at least one unexpected consequence; the opportunity for bacterial pathogens to expand and spread prior to planting. The greenhouse environment in which pepper seedlings are produced, if not managed properly, is highly conducive to bacterial leaf spot. Bacteria present on only a very small number of seeds (e.g. 1 in 10,000) can become a significant threat in some greenhouses. The following are practices that will reduce the threat of bacterial leaf spot: 1) practice good sanitation in the greenhouse; 2) use chlorine bleach-treated seeds; 3) do not raise exotic or experimental pepper or tomato varieties, or saved seed, in the same greenhouse with commercial seedlings unless all seeds are treated; 4) keep the greenhouse as dry as possible.

4) Optimize crop rotation and site selection. Crop rotation is an important strategy that not only reduces disease problems but also affects weed, insect and nutrient management. While in some areas, due to population pressures and other factors, land well suited for vegetable production may be scarce; in the long run it is best to rotate crops as much as possible. Crop rotation should be done among crop families; for example, peppers are Solanaceous crops, as are tomatoes, eggplants, and potatoes. Plants in the same crop family often share the same or related pathogens, and thus should never be used as rotational crops with each other. For bacterial leaf spot management, a relatively short rotation of two years out of Solanaceous crops is adequate. However, longer rotations would reduce other pathogen populations and should be considered if possible. Site factors to consider for pepper production that will minimize opportunities for bacterial spot development include good drainage and good aeration. These will reduce the amount of time that plants are wet after irrigation or rain, resulting in fewer opportunities for Xanthomonas and other pathogens to multiply and spread.

5) Use cultural practices that minimize disease spread. Increasing the organic matter content of soil not only improves crop growth and yield, but may also reduce some diseases. Organic amendments such as compost and manures are widely used in this context and should be considered if available within a practical distance from the farm. Organic amendments are best applied in the fall or early spring to allow leaching of excess salts from composts and destruction of any pathogens in manures. The benefit of composts is maximized with high quality composts that have undergone optimal heating to kill weed seeds, pests and pathogens. Other cultural practices are carefully controlling irrigation to minimize the time when plants are wet, and to avoid handling plants when they are wet.

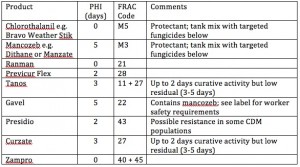

6) Use bactericides as needed. There are no really good bactericides for bacterial leaf spot control in peppers. They are especially ineffective in stopping the disease under favorable environmental conditions once it has become established. The combination of maneb or Manex with fixed copper compounds can be used to help prevent the disease. Depending on the weather, variety, history of the field, whether or not the seeds have been treated, and other factors, this bactericide can be applied on a 5-14 day basis after transplants are placed in the field. Maneb is an EBDC fungicide, which some processors have banned, so it is necessary to check with customers to determine if it is allowed. Many strains of Xanthomonas are insensitive to some degree to copper, so copper has become less effective over the years. If the other steps in the integrated disease management program have been followed, however, the need for bactericides is significantly reduced.