Last week my students and I read three different scholars writing about Yury Tynianov, the formalist literary theorist, literary historian, and writer of historical anecdotes and biographical fiction.

I first explored Tynianov with my professor, Yury Konstantinovich Shcheglov, while I was still in graduate school. Prof. Shcheglov was fantastic — a wonderfully intelligent and deeply compassionate and thoughtful man whose knowledge of everything from eighteenth century Russian poetry to contemporary American fiction amazed and amused me in the years I knew him. (More about that last later.) His erudition was legendary, as was his absentmindedness. Once I met him in Van Hise Hall, the languages building at Wisconsin. “Angela,” he greeted me enthusiastically. “I’m so glad to see you! Do you know where the exit is?” We were on the fourth floor, a floor with glass doors opening out in several directions, including toward the parking lot where he kept his car while teaching. (No, he didn’t drive, but his wife did. Thank goodness on both counts.) I gently grasped his arm and turned him away from the elevators and toward the proper door.

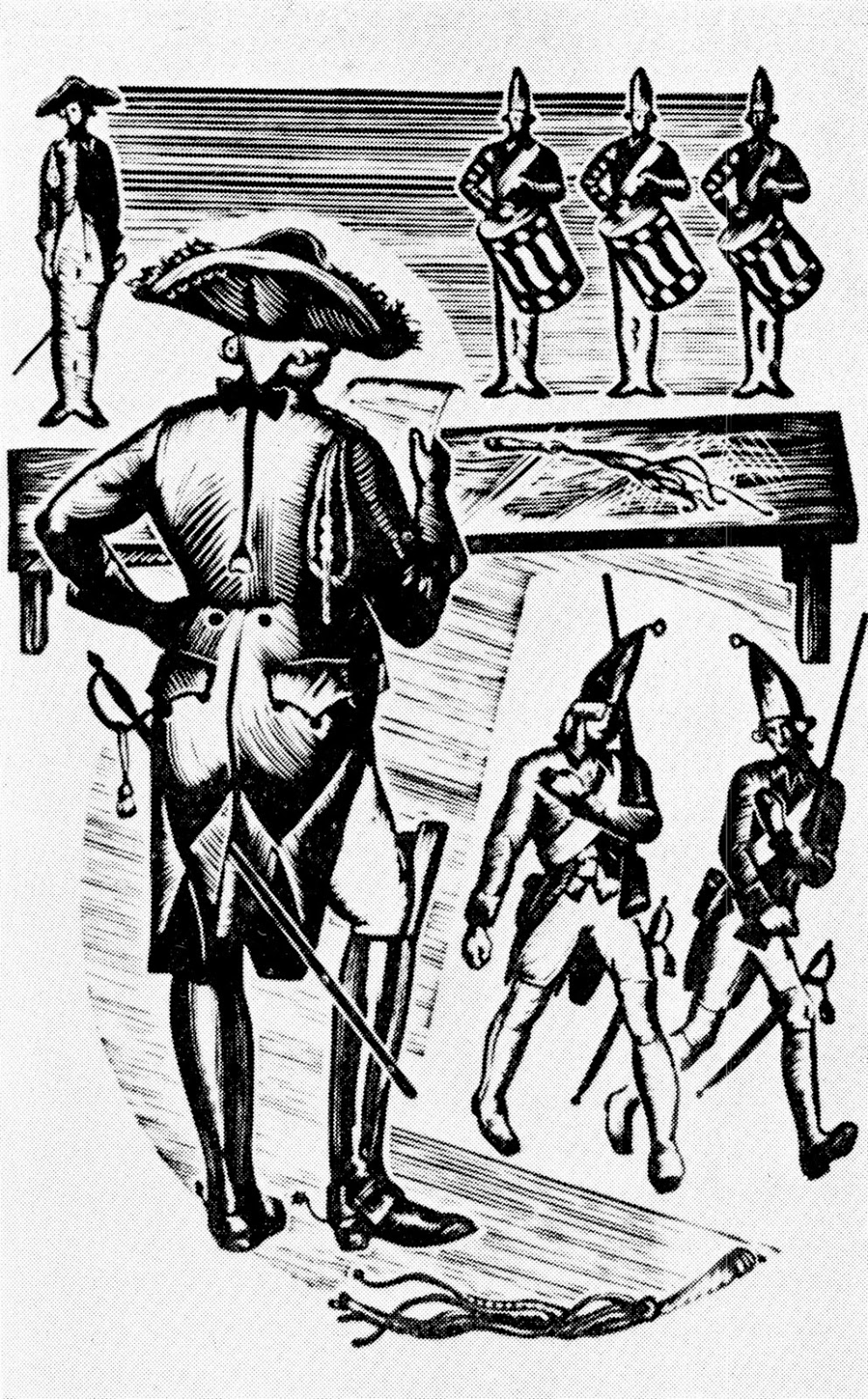

|

| R.D. Yakhnin, Illustration for Lieutenant Kizhe |

One semester I did an independent study with Prof. Shcheglov, reading Tynianov’s three stories set in the reigns of Peter I, Paul I and Nicholas I, trying to isolate the characteristic that linked them. My conclusions?

Each story was “believable” not only because each was infused with a special paranoia unique to its respective tsar, but also because its language was inflected with vocabulary and verbal structures from the appropriate era. Tynianov was a chameleon, able to endow his narrators with just the right linguistic coloration.

My dissertation and first book emerged from that in-depth study of Tynianov, which meant that reading two chapters fromWriting a Usable Past with my students was for me a journey back to the years when I first wrote some of those sentences — over twenty years ago.

About the same time as me, another scholar was writing her dissertation at Columbia — Ludmilla Trigos, whose work on the Decembrist myth also brought her to study Tynianov. My book came out before her article on Kiukhlia, which in the scholarly world means she had to cite me rather than the other way around, though we probably had similar ideas simultaneously. (Avril Pyman, the third scholar, did not cite us.)

Prof. Pyman’s piece, in the Mapping Lives book we are using as a kind of “textbook,” detailed Tynianov’s theory and practice, and several of the students seemed frustrated that there was no real attempt to integrate the two. But both Milla and I, it seems to me, came up with our own ways to finesse this point, identifying the cutting back and forth from one consciousness and even location to another (Milla, in Kiukhlia, about Kiukhelbeker and Nicholas I during the Decembrist revolt) and a deliberately “have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too” explanation in The Death of the Vazir-Mukhtar (me) where Tynianov “footnotes” his sources for those who want to explore the contradictions and vacillations of his portrait of Griboedov.

In class we talked about archives and sources and readings: what was “true” and what needed to be documented. Tynianov famously stated: “where the document ends, that’s where I begin,” but he also tried to claim a status as a prophet, that sometimes he instinctually wrote something and only found the proof later. A complicated individual, but a talented one.

|

| The protagonist of Twelve Chairs, Ostap Bender, here in Gaidar’s classic film. |

Speaking of which: Yury Konstantinovich. Some of his most brilliant published work was his commentaries to Ilf and Petrov’s novel Twelve Chairs. I tried to convince him to translate them into English for use as a teaching aid, but by then he had too many other projects he wanted to pursue.

He may have had a similar problem when I asked him to work with me back in 1992.

Faculty never get any “credit” for teaching independent studies; we do it out of our own intellectual interest and/or the goodness of our hearts. So when I asked Yury Konstantinovich to work on Tynianov with me, he proposed a bargain. “First, you will write a serious paper, 25-30 pages, by the end of the semester.” This was pretty scary for me at that stage, but I agreed. “And second, we will spend five-ten minutes at the end of every meeting talking about this paperback novel. I will mark pages for you to tell me: is this normal American English, or is it in some way linguistically marked, so that an American reader would find it unusual?” The novel was The Silence of the Lambs, and yes, much of it was unusual. Adorable, though, that this famous and brilliant scholar was so engaged with the culture around him that he was intensely curious about the literary language — even though he might not always know how to exit the building.