Coming to Bayeux has been one of the most intriguing, thought provoking, and worthwhile trips I have taken. This sleepy, French town is packed with citizens and tourist alike during the day and by 9 pm there is barely a soul in sight. I’ve dined on more baguettes and pastries than I ever have before (especially since I haven’t eaten anything with gluten in it in almost 2 years). I’ve eaten and enjoyed escargot, duck, chicken liver in an apple/calvados based sauce, real strips of bacon on a salad (attention America: let’s get behind this idea, no more bacon bits!), and SO MANY CREPES. Aside from the tourists who are obviously visiting to see the nearby WWII sights and souvenir shops, there’s no major evidence that the town had once been occupied by German soldiers and was liberated soon after D-Day. A few short bus rides from the town told a different story, though. At Pointe du Hoc, bomb craters and the remains of bunkers were strewn throughout the cliff. Evidence of one of the toughest objectives of D-Day was all around us. Of about 250 Rangers who took Pointe du Hoc, only 90 were able to fight again in the war.

A German bunker that survived D-Day at Pointe du Hoc

Taylor and I standing in a bomb crater at Pointe Du Hoc

The bombings didn’t stop after D-Day. One common theme that came up throughout the museums and films we saw was the French civilian suffering of allied bombing during the liberation of France. I unintentionally sparked a debate on the portrayal of French suffering after watching the short film “100 Days of Normandy” that was shown in Arromanches. While I did disagree with some of the others on a few small points, I felt that the majority of our disagreement was actually a misunderstanding of my criticism – especially since I was still chewing over all of the information I had taken in over the last few days. Wandering the streets of Bayeux on my last night here gave me the opportunity to really think on all of the information I’ve learned here in Normandy.

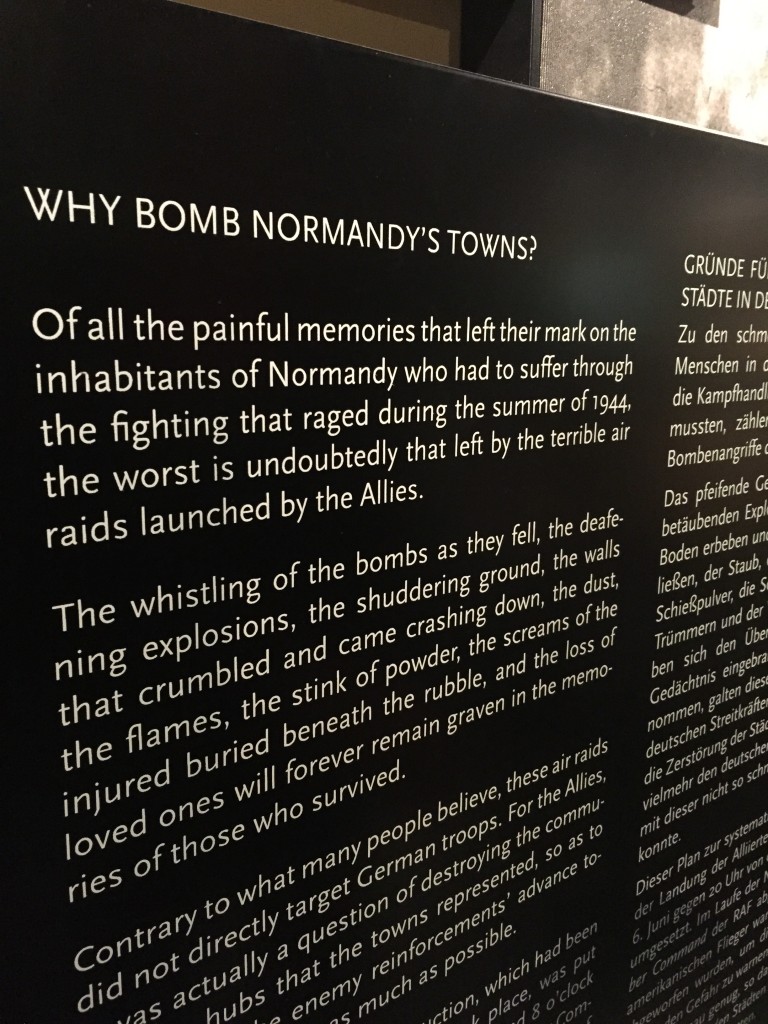

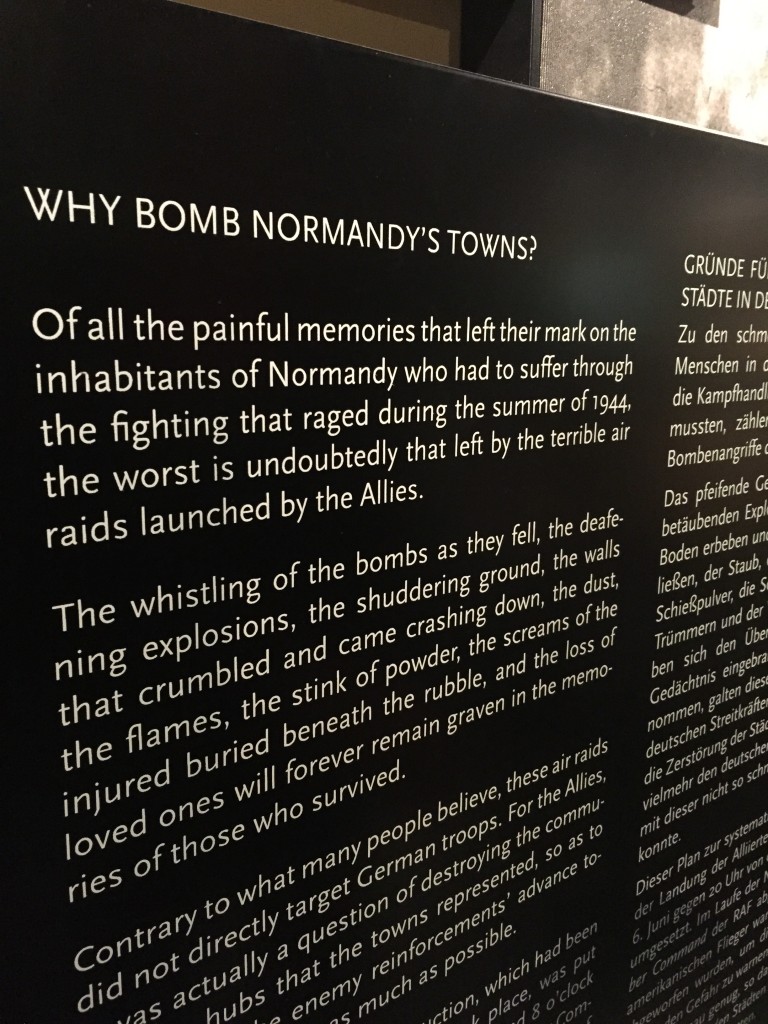

The French experience during WWII was unique. In 1940, France fell to Germany and the German occupation of France began, not ending until the liberation by Allied forces beginning on D-Day, June 6, 1944. The first indication I saw of a difference in the WWII narrative was in the Caen Memorial Museum. There was an entire section of the museum dedicated to French life during occupation and liberation. In this section, one panel addressed the question of Allied bombing of the French countryside. Strategic bombing of the French towns and railways were crucial to securing the defeat of Germany and had been approved by the French Resistance leader, Charles de Gaulle. The panel, part of which I’ve shown here in this blog, really took me by surprise when I first read it. It is extremely critical of the Allies and their methods of securing freedom for France. The text following the question “Why bomb Normandy’s towns?” did not explain the reasons behind the bombings; rather it seemed to be a question posed to the U.S. itself.

This panel, located in the Caen Memorial Museum, criticized the use of and effectiveness of Allied strategic bombings on the French countryside.

This sort of language appeared repeatedly throughout the various museums, but in my opinion, it appeared most strongly in “100 Days of Normandy.” There were many sequences of shots depicting allied bombing, then showing French women and children. Towns were destroyed. The French people were suffering. The destruction depicted in the film inflicted by the Allies, not the Germans. The Germans were shown surrendering, but all shots of bombardment were from the Allies. In my interpretation of this film (because there can be more than one), I believe the director was once again asking the question: “Why bomb Normandy’s towns?” When I was asked my opinion of the film, I responded that it left a bad taste in my mouth, which received some backlash from nearly everyone else. I tried to explain (unfortunately with a poor choice of words) that I believed the film presented a skewed view of WWII. The best way to explain this belief, I think, is to look at the U.S. narrative of WWII.

In the U.S., we aren’t taught about the suffering and bombing of the French people. Before spring semester, I had been completely unaware of the magnitude of French civilian casualties of the war. I knew that there had been some strategic bombing, but I was never fully aware of the implications it had on civilian life and death. Even then, it is difficult to imagine through reading the damage that can be inflicted by bombings. It wasn’t until I was standing in a 71-year-old bomb crater that I even began to fathom the destruction that was inflicted on the French countryside. The American narrative in the European Theater only has one theme: liberation. We were always taught that the U.S. was essentially savior of the French and all other countries under German occupation. This narrative focuses on national pride and gives the American people cause to believe in our country’s leadership and aims. There’s so much more to WWII, though! By promoting national pride, we’ve completely ignored the suffering we caused.

Now, let’s look again at the French narrative. How can a country bounce back from falling to Germany in less than two weeks? From collaboration with the Nazi regime? From needing to be liberated? The focus on elements that will bring them together – national pride. All of the museums highlighted the role the French Resistance played in the success of D-Day operations and the liberation of France (to an extent that almost seemed to exaggerate its role). They memorialized the citizens they lost. The entire country came together to remember these people and to rebuild instead of focusing on the German occupation. By ignoring and trying to forget the occupation, the necessity of Allied bombing comes into question. Thousands of French civilians were killed by Allied bombing – not German bombs. There is no doubt in the American narrative that the bombing was necessary to end the war, but in France, the bombings are called in to question and the Allies are criticized.

With all of this said, I will still say that the film left a bad taste in my mouth. It’s the same taste that is left when I (now) read American history books that exclude the French perspective. My time in Normandy has allowed me to really contemplate the true issue: the fine line between promoting national pride and distorting complete historical picture. To me, both the U.S. and France have crossed that line and contributed to misconceptions about the war. I believe 100% that it is important to remember the French civilian casualties caused by the American bombings, but I also believe it is important to remember why the bombings were necessary and the contributions they made to the war effort in shortening the war and reducing overall casualties. The experiences I’ve had here in Normandy have truly opened my eyes to a new facet of the war – one that I could never have even comprehended before coming here.