My husband and brothers-in-law are in an album club hosted over Discord. Over the course of two-ish weeks, they each listen to an album nearly ten times, then write up a few surprisingly formal paragraphs about the material.

At first, I wanted to participate in the fun. Like most people, I consider myself a music-lover, I think I have good taste, and I also struggle to believe that people will continue to survive without hearing my very important opinions on everything. But the idea of listening to the same album seven, eight, nine, or more times over the course of fourteen days didn’t sit well with me. Part of me wasn’t prepared to give that kind of focus to something, but I also felt ill-equipped because I am still processing the work of artists I started listening to years ago. If after who knows how many listens I still don’t know quite how I feel about Rumours (though, generally: yes, very good… except what happened with Oh, Daddy?), how can I expect myself to have anything to say about an album that is still so new to me?

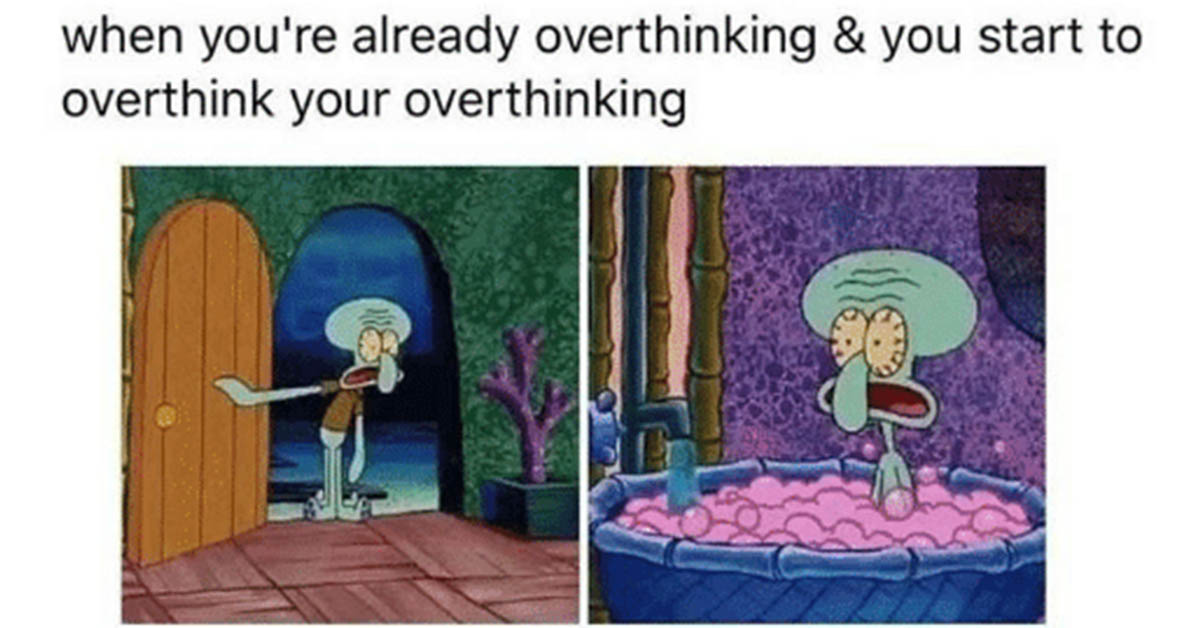

I am an iterative thinker (or a ruminator, if my mother is to be believed). I’m also an iterative reader, listener, writer. Recursion continues to show up in my life in many ways, and I am still learning to suspend my anxiety about it (a semester of Data Structures and Algorithms is enough to make anyone’s palms sweat at the thought).

I am an iterative thinker (or a ruminator, if my mother is to be believed). I’m also an iterative reader, listener, writer. Recursion continues to show up in my life in many ways, and I am still learning to suspend my anxiety about it (a semester of Data Structures and Algorithms is enough to make anyone’s palms sweat at the thought).

I am always coming back, reviewing, adding, taking away. Revision is the sine qua non of my existence. I feel like I could toy with one idea forever, if only there weren’t so many others. Sometimes this abiding curiosity feels like a vigil: sitting, waiting, watching. Usually I think what you’re watching for is most important. What you find changes who you are.

But, in a larger sense, this rumination is one of the consequences of literacy that Goody & Watt discussed in their paper. A study conducted by the University of Michigan found that 73% of people between the ages of 25 and 35 are chronic over-thinkers. While this statistic falls with age, it remains significant: as creatures, we are obsessive. Maybe this is because reading and writing gives us the opportunity to revisit ideas constantly. Our shifting understanding of time and history permits us to linger, and then walk away… and then come back. At the same time, we are prone to revisionist histories in the same way that the oral cultures we discussed are: we change our minds with new information, according to our needs. Our ideas don’t stay static. We struggle to agree on facts, even though we each believe that facts exist. This revision, too, has been made a literary process. The second reading of a text is different from the first.

Malcolm X described his literacy as freedom. I wonder if he found a sweet spot between illiteracy and rumination.