Written by Craig Gibson, Professor & Professional Development Coordinator and Drake Institute Faculty Fellow for Mentoring

During this pandemic-inflicted year (or more), all of us have experienced a range of experiences, emotions, interactions, hopes, and fears as we’ve thought about our work—our practice as professionals and as members of the university community. Time itself has become an uncertain and radically more subjective space, with the markers of days and weeks and signposts of events blurring, with some recognizable features but with more uncertainty and searching for stable milestones in our work and in our personal lives. Commentary on this uncertainty appears often in major media outlets, in blog posts, and in articles and books. We are living in an unmoored space, seeing each other across virtual meetings in Zoom rectangles, through phone calls, in emails, and occasionally in person, but the reality of teleworking for many of us has lessened connection and also presented opportunities for reflection on the uncertainties enveloping us. We are living, in effect, in a “liminal space.”

I am pointing to the idea of “liminality” here to raise some important issues about our work with our students and faculty. I first learned about this notion of “liminality” while co-chairing an ACRL Task Force, the one that created the Framework for Information Literacy, the generative and often controversial document that continues to cause interest, some disagreement, and productive discussions among teaching librarians. The theory behind the Framework, Threshold Concepts theory, posits that students or novices must learn the foundational and often counterintuitive ideas in any discipline by traversing a “liminal” space with uncertain markers and guideposts, with many questions, with unsettling ideas, that may upend students’ comfortable, unquestioned, and previously naïve conceptions about the discipline. The student must live with uncertainty for an extended period, the theory goes, in order to emerge with greater understanding of that field, its ways of thinking, the way its scholars and experts talk and write, their habits and signaling and the accepted norms of professional communication within the field. Only in moving through that emotionally challenging and difficult space of liminality can the student emerge as an expert, or at least more expert-like in habits of mind, and in understanding the big ideas of the discipline that organize the mental universe of the field. The student may oscillate between more expert-like thinking and revert to earlier naïve notions while in the liminal space, and that traversing through the fog of uncertainty is necessary for the pain of learning to occur.

I well recall, during one of the rich conversations in our ACRL Task Force, that one of the early adopters of Threshold Concepts theory in our profession observed that “threshold concepts themselves are a threshold concept for our profession.” She remarked on the collective “liminal space” that teaching librarians were living through in even considering this theory and adapting it to their teaching practices. Questions abounded during those years during virtual open hearings and at ALA conferences, and at other events, about our teaching role: how can these very complex ideas possibly be taught in our one-shot instruction sessions, which are our bread-and-butter approach to instruction? How can we possibly assess learning outcomes for these messy, complicated ideas? Shouldn’t we be focusing on the specifics of teaching databases and style guides and the immediately useful information students need for assignments given by faculty? How can our limited opportunities for teaching possibly reach for programmatic development if we tie ourselves to a theory developed outside the library profession, that many faculty hadn’t even heard of? These questions, among many others, challenged me and others, but we grappled with them, and understood that we were in our own liminal space in effecting change at scale across the profession. We made changes in multiple versions of the Framework through listening, responding, respecting a wide range of perspective offered by colleagues, while keeping our core principles about the emerging Framework before us. It was, as we often say, a learning experience.

I reflect now on the liminal space we’ve been traveling as a profession since the idea for the Framework first emerged from our Task Force’s discussion eight years ago, and see greater understanding of shifts in our teaching role because the Framework has provoked so much discussion, debate, and reflection. Some institutions have adopted it readily and have created structured curricula, partnering with Writing Programs, based on its elements of threshold concepts, knowledge practices, and dispositions. Others have taken parts of the Framework and created assignments or specific courses based on its elements. Some have adhered to an older—and in my view, outdated– set of Information Literacy Standards created over twenty years ago, which do not address the information challenges of this time. Among these are the authority/expertise problem, the reproducibility and data fraud problem in many science and social science fields, the misinformation/trust problem in media environments, the ideology/truth claim problem occasioned by Critical Theory in some humanities, the algorithmic mysteries of search engines and social media, and a general attention problem because of the bursts of information coming at us in our professional and personal lives. Sense-making as professionals about our teaching role as librarians is more challenging than ever in these times.

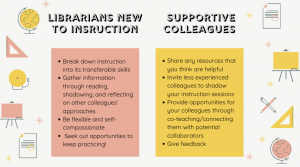

However, the liminal space we continue to traverse together offers opportunities for learning together. I have learned, through conversations and discussions with colleagues here and elsewhere, that our teaching role, whether based on the Framework or not, needs to be reimagined. We will need to navigate a difficult space of teaching in more traditional ways, face-to-face, in single instruction sessions, while planning for, and reaching toward, larger and deeper partnerships that build larger communities of practice for pedagogical innovation. We need architectures for deeper learning, multiple pathways that produce integrative learning, across longer trajectories of learning, in order to effect deeper educational change. The lesson from liminality here, for our profession, is that the uncertainty created by myriad disconnected one-shot sessions that don’t build toward something larger, leaves us in instructional limbo, in a service provider role, that of the occasional lecturer or guest presenter. Such a role matters, but what can be imagined based on it matters more: that of educational partner—in designing assignments and curricula, in joining communities of practice related to teaching development such as those sponsored by the Drake Institute at Ohio State, or in joining groups sponsored by academic departments reorganizing General Education courses, or in creating new ones founded on partnerships. The educational partnership role is vital for our continued success.

Another lesson learned from the liminal space opened up by the Framework is that the technocratic perfectionism of lesson plans and learning outcomes clearly specified, based on the previous Information Literacy Standards (or any other set of Standards), do not achieve the deepest learning possible, and don’t support the wide variability among students. We have learned much about assessment in our profession in the past decade, with proliferating presentations and articles about it, but learning outcomes that eliminate the spontaneous, the charged luminous moment in the classroom, the too-carefully managed activity, often remove the possibility for learning. Our students need to learn the vagaries and uncertainties of the research process, and too often our presentations and lessons are too “packaged” to give them that reality—the challenges of living with liminality themselves in working with disciplinary ideas in concert with information literacy concepts. A good example is teaching how to formulate a research question that is “researchable”: this is the reality that scholars and researchers grapple with all the time, but their expertise allows them to move quickly to another line of investigation, a reframed question, a new population, another perspective. Students need to be taught in depth that “Research is Inquiry” (one of the Framework’s big ideas), and to modify questions and develop better ones as they work through dead ends and uncertain lines of investigation. Only the extended experience of liminality disciplines their minds and their habits to develop better questions worthy of inquiry. That extended experience of productive liminality can only be provided by thematic connections provided by the Framework, or other uber-concepts, across time, as students grapple with those ideas together and with faculty working with them—not necessarily always as unquestioned experts, but as co-learners.

Another lesson from liminality in working on the Framework, and in reconsidering our teaching role in working with disciplinary faculty, is that faculty themselves are often the most neglected learners on campus (Rossing and Lavitt). Surely this is a counterintuitive “threshold concept” in itself! After all, faculty are highly educated, are experts in their field, have published extensively, conducted multi-year scholarly projects, have presented at conferences, and have sustained professional conversations with colleagues worldwide about the leading-edge questions in their fields. However, most faculty learn about teaching, if at all, episodically, and they are neglected learners in the sense that they often teach in solitude and may lack the time and commitment to make their expertise and knowledge more accessible to students and to a wider public. Professional learning programs offered through Centers for Teaching and Learning on many campuses, and through the Drake Institute at Ohio State, provide opportunities and venues to create community and collective learning to make that knowledge come alive for more students, with more diverse students, and to a wider community, and enliven interdisciplinary conversations that create a more vibrant intellectual climate. How can librarians become part of those interdisciplinary conversations? We need to learn, more deeply than before, how scholarly conversations and influence work, how faculty are incentivized, and learn the language of complexity within disciplines, but also across them. Our teaching role in communities of practice, in research partnerships such as those offered by the Office of Research at Ohio State, and in many “small significant conversations” on campus (Roxa and Martensson), can coalesce to help us, with our partners, move through our collective liminal space toward a reinvigorated community—beyond this pandemic time, but more importantly, toward a revitalized time of real community where all contribute and make learning more sustained and vibrant for all who teach and learn together.

Sources for further reading

Rossing, Jonathan P., and Melissa A. Lavitt. “The Neglected Learner: A Call to Support Integrative Learning for Faculty.” Liberal Education 102, no. 2 (Spring 2016): 1–10.

Roxå, Torgny, and Katarina Mårtensson. “Significant Conversations and Significant Networks—Exploring the Backstage of the Teaching Arena.” Studies in Higher Education 34, no. 5 (2009): 547–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802597200