An Inca quipu from the Larco Museum Collection

(Inca_Quipu.jpg, taken from Wikipedia.org <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quipu>)

Prior to Spanish colonization, the native peoples of the South American Andes, while having several distinct spoken languages, lacked any sort of written language or system of writing. Yet, especially during the Inca empire, they somehow managed to keep track with extraordinary accuracy of accounts, tribute payed and owed by the population, dates, stars, even historical events and more. The secret was lengths of knotted cords called “quipus.”

“Quipu,” simply enough, translates to “knot” from its native Quechua, the predominant native language in most of South America. Each quipu consisted of a thick length of cord (made of cloth, rope, llama hair, etc.) with many smaller cords hanging from it. In these smaller cords, various types of knots would be tied, different knots having different meanings. This is how the quipus were read.

A quipu in the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (quipu-new.jpg, taken from Newsdesk.si.edu <http://newsdesk.si.edu/snapshot/quipu>)

Looking closely, particularly at the shorter cords on the left, you can clearly see different types of knots tied throughout the hanging cords. While mostly associated with the Inca, quipus were actually in use long before the beginning of the Inca empire.

Quipus, despite their simplistic nature, were actually very complex pieces of technology often praised as such by the early observers of Andean society. On their simplest level, quipus were perfect for recording city populations. The most common use of quipus that can be gleaned from colonial records and research, though, is keeping track of tribute payments. In the Inca society, citizens were expected to pay a regular tribute of food, chicha (an alcoholic beverage made from maize), livestock, clothing and other goods, much like monetary taxes today. Inca accountants would keep track of who had payed what on quipus. That, though, is only one thing they were used for. Research into ancient quipus has turned up numbers correlating to those you might find on a calendar (days in a month/year, months in a season, etc.), adding up with startling accuracy. Some may have even been used to track the movements of other nearby planets. And while there is little proof that the knots on quipus represented anything more than numbers, there are documents that tell of them being used to keep track of historic events, including colonial writings telling of natives using quipus to tell conquistadores of times before the Inca empire.

Fun fact: The native South and Central Americans are among the first known civilizations to have a way of representing the mathematical concept of nothingness (in other words, the number zero)

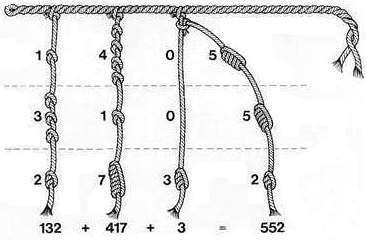

Quipus were read using several factors: the types of knots used, the positioning of the knots on the cords, and the color of the cords. It is generally agreed that most quipus were used for counting, and keeping track of numbers. Quipus used a decimal system of counting. The knots at the bottom of each cord represented units. The knots above those represented tens, the knots above those hundreds, and so on up the cord.

(quipu2.jpg, taken from jisuchoi.com <http://www.jisuchoi.com/blog/?p=313>)

A figure-eight knot represented a single unit at the bottom of the cord, the units place. A multifold long knot, as it is called, was tied into the units place to represent numbers between one and ten (so, two through nine).

(quipus_4_incas.gif, taken from contenidosdigitales.ulp.edu <http://contenidosdigitales.ulp.edu.ar/exe/sistemadeinfo_cont/el_quipu.html>)

Standard overhand knots represented units of ten, so that a single overhand knot in the tens place on the cord equals ten. Two overhand knots in the tens place would equal twenty, and so on. A single overhand knot in the hundreds place equals one hundred, two knots equal two hundred, and so on. This is the same for thousands, ten thousands, up to hundred thousands and over, if necessary (though there are few records of quipus counting that high).

There are three groups of knots on the first cord on the left. The one at the top represents 100, the three in the middle 30, and the twofold knot at the bottom 2. So the first cord shows the number 132. The other cords, with the exception of the last one hanging off on the right (the summation cord), are counted the same way. (paint3.png, taken from incaglossary.org <http://www.incaglossary.org/appc.html>)

Some quipus also included summation cords tied off the end of a group of cords, using long knots in every unit space to show the total of all the cords in the group. Some quipus consisted of cords of various colors. These colors were deliberate, different colors or patterns having different meanings (yellow cords might count gold, red cords might count soldiers, etc.).

There is much speculation as to whether or not quipus were represented some form of communication beyond numbers. As said by the man is this video, there is a theory (though he seems rather sure of its truth) that some quipus were read as a sort of binary code. There are also colonial documents that tell of Andeans using quipus to tell stories or memorize messages/prayers, though it is unknown how they did so. It has been suggested that the messages were not actually read from the quipus, but that the quipus served as a memory aid to already learned messages.

Usually, quipus were kept and read by a special class of nobility. These were called quipucamayocs. They are also referred to as quipucamayuc, quipucamayu and quipucamayo in different texts.

An etching of a quipucamayoc, as it appears in a lengthy letter to the king of Spain, written by the Andean Guaman Poma. (INCAS5.gif, taken from historiacultural.com <http://www.historiacultural.com/2009/04/organizacion-administrativa-decimal.html>)

Though not necessarily the only ones who knew how to read quipus, it was the quipucamayoc’s job to keep count of the various quipus used by the nobility, and read the quipus to them as desired. Quipucamayocs created and kept track of quipus concerning population, tribute, military operations, organized labor projects and more.

Writings say that quipus were also sometimes used by messengers called chasquis. Chasquis were positioned in three-mile increments along the roads between cities. One would be given a message to deliver to another city, and he would run to the next chasqui down the road and tell him the message, so he could tell it to the next and so on until it reached its destination. Sometimes one or more quipus would also be given to the chasqui to deliver with the message.

Image of a chasqui carrying a quipu (Chasqui_Inca_Peru.jpg, taken from meximayan.com <http://www.meximayan.com/Archaeological%20Articles/Archaeological_Articles.html>)

Though many Spanish colonizers were fascinated and impressed by quipus, they were also seen as a threat. Spaniards thought that the quipucamayocs were more loyal to their local rulers than to the Spanish crown, and that they would lie about what was recorded on the quipus. The church also saw quipus, along with many other aspects of Andean culture, as idolatrous and blasphemous. In 1583, a decree by the church council of Lima denounced quipus as the worked of the devil, and demanded they be destroyed. Though many quipus were destroyed and their used was discouraged, quipus did continue to be used for quite a while after. Eventually, though, as the native Andeans were assimilated into Spanish colonial culture, the use of quipus died out.

Quipus are no longer used in Andean societies today, and there is veritably no one who still knows how to create or read quipus correctly (as they were traditionally used, at least). There are some small villages, though, that still use quipus in a way. Tupicocha is one such village, which was visited by researcher Frank L. Salomon, who studied the quipus used by the people there. While not as complex and all-encompassing as ancient quipus, the villagers still use quipus todayto keep certain government records. The quipus also hold symbolic importance, and are used in special ceremonies when passing authority on to a successor.

And, while difficult to find, there are a very scarce few people in the Andes who still use quipus as their main method of record-keeping, such as the grandfather mentioned in the first video and the old man in this one. (skip to around 3:30)

Sources:

Day, C. (1967). Quipus and witches’ knots. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press.

Martin, C., & Wasserman, M. (2011). Readings on Latin America and its people. (Vol. 1). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Means, P. (1964). Acient civilizations of the Andes. New York, NY: Gordian Press, Inc.

Molina, C. (2011). Account of the fables and rites of the incas. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Nordenskiöld, E. (1925). Comparative ethnographical studies: The secret of the peruvian quipus. (Vol. 6). Brooklyn, NY: AMS Press.

Salomon, F. (2004). The cord keepers: Khipus and cultural life in a Peruvian village. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.