Wooster’s Scarlet, Gray and Green Fair returns after a one-year hiatus on Tuesday, April 22 — Earth Day. Full story …

Wooster’s Scarlet, Gray and Green Fair returns after a one-year hiatus on Tuesday, April 22 — Earth Day. Full story …

Month: February 2014

Focus on your forest’s future

Selling trees for timber? Do your homework first, says a CFAES forestry specialist: Make it work and be good for both you and your woods, both now and into the future. Two upcoming workshops can help you.

Selling trees for timber? Do your homework first, says a CFAES forestry specialist: Make it work and be good for both you and your woods, both now and into the future. Two upcoming workshops can help you.

Busy weekend

The Cleveland Plain Dealer’s Debbi Snook covered Friday’s ECO-farming workshop and Saturday and Sunday’s Ohio Ecological Food and Farm Association annual conference. CFAES experts led the former and gave more than a dozen of the 100-plus sessions at the latter; the former was part of the latter.

Bees, bad beetles turning blue?

CFAES’s Dan Herms talks about Ohio’s cold winter and its impacts on the exotic, tree-killing emerald ash borer … and on the domesticated, hive-living honey bee. The big freeze may have hurt one of them; the other, not so much. Watch (1:30).

Something’s brewing

Things are hopping today at OARDC. Witness the birth of an industry? OARDC is CFAES’s research arm. Related post.

Even more Buckeyes now making a difference

Ohio State now ranks No. 4 as a top producer of Peace Corps volunteers, up five spots from 2013. The university’s Peace Corps program falls under CFAES.

Ohio State now ranks No. 4 as a top producer of Peace Corps volunteers, up five spots from 2013. The university’s Peace Corps program falls under CFAES.

CFAES, Tanzania team up to shape next generation of Extension educators

Getting information to and from farmers is a huge challenge in Tanzania, a nation the size of Texas and New Mexico combined. Of the country’s 45 million people, 80 percent are engaged in small-holder agriculture and have limited access to new production information or knowledge of agricultural markets.

Getting information to and from farmers is a huge challenge in Tanzania, a nation the size of Texas and New Mexico combined. Of the country’s 45 million people, 80 percent are engaged in small-holder agriculture and have limited access to new production information or knowledge of agricultural markets.

Catherine Msuya, head of the Department of Agriculture, Education, and Extension at the Sokoine University of Agriculture (SUA) in Morogoro, Tanzania, points out, however, that the number of farmers who are sufficiently informed of the aspects of agriculture can increase through improved Extension services in Tanzania.

“Right now farmers ask, ‘How can I improve my production and where can I sell my crops? How can I add value?’ ” said Dr. Msuya (pictured with Gary Straquadine, chair of CFAES’s Department of Agricultural Education, Communication, and Leadership). “Farmers in Tanzania do not have easy access to this knowledge right now, but Extension can help them.”

Better Extension training and farming, greater food security

Disseminating this knowledge to rural farmers is a substantial challenge. For Extension professionals to help farmers increase production and add value, they must first be adequately trained and prepared to properly work with farmers in a way that addresses farmers’ needs.

Dr. Msuya visited CFAES from Jan. 26-31 along with two other Tanzanian colleagues: Anne Niediwe Assenga, director of training in the Tanzanian Ministry of Agriculture, Food Security and Cooperatives (MAFC), and Joyce Kuliwaki Mvuna, assistant director of Extension services in the Ministry’s Crop Development Division. Through their weeklong visit to CFAES, they learned about how to improve the training of future Extension educators in Tanzania and about methods for integrating agricultural research and Extension activities, which will ultimately provide farmers with better access to new production technologies.

The visit to Ohio State by the three Extension administrators was not by coincidence. The university, through the Office of International Programs in Agriculture (IPA), administers a major U.S. Agency for International Development-funded food security initiative in Tanzania, named iAGRI, in collaboration with SUA and MAFC. This project also involves five other U.S. land grant universities and other institutions in Africa and India. The goal of iAGRI is to improve food security and agricultural productivity in Tanzania by strengthening the training and research capacities of SUA and MAFC.

Providing new, better tech to Tanzania’s farmers

“Extension plays a critical role in working with farmers in Tanzania and seeing that improved technologies get to them,” said Mark Erbaugh, IPA director, “and through collaborations with our Extension and academic faculty we hope to forge future collaborations that can help improve the capacity of Tanzania to provide more effective Extension services.”

Meetings were arranged for the visitors to discuss their programs and challenges with faculty from OSU Extension; the Department of Agricultural Communication, Education, and Leadership; the Agricultural Technical Institute (ATI); the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center (OARDC); and the Center for African Studies, through its director, Robert Agunga.

Ms. Assenga, who administers agricultural Extension training programs for Tanzanian students, emphasized the need for adequate infrastructure and technology to build her country’s capacity to meet an increasing demand for food. Currently agriculture in Tanzania is responsible for 95 percent of the food consumed by the country’s citizens. When current population growth and challenges related to climate change are considered, this number assumes an even greater level of significance.

Support for Tanzanians’ growing entrepreneurship

Ms. Assenga added that the agricultural sector in Tanzania has been growing around 4 percent in recent years, but in order to adequately contribute to Tanzania’s economy in the coming years, it will need to grow at least 6 percent, and ideally 10 percent, per year. For this growth to occur, Extension services will play a key role in helping famers expand their current capacities in all respects, from production to marketing.

Individual Tanzanians are prepared to work toward overcoming these challenges through their own innovation as well. According to Ms. Assenga, students are expressing an increased interest in self-employment, not only out of concern that they won’t be able to secure jobs in government institutions or other sectors, but also because self-employment allows them to chart their own path to self-sustainability.

The Ministry of Agriculture views this entrepreneurial spirit as promising and is seeking to foster this interest through curriculum development and innovative outreach methods, including online learning. Ms. Mvuna enthusiastically shared that the Ministry plans to initiate “e-Extension,” an online program that is intended “to improve Extension service delivery and accelerate the dissemination of information in Tanzania.” Webinars and online conferencing are tools that OSU Extension educators already use extensively to connect with various constituents, whether farmers, natural resource professionals or consumers.

Visit opens doors to further teamwork

Their visit to Ohio State has opened doors for substantial future collaboration: OSU Extension staff now have opportunities to help their Tanzanian counterparts meet programmatic objectives related to food security, and also to learn about the challenges confronting their Extension counterparts and others involved in Tanzanian agricultural production.

Before their departure, the women expressed their gratitude on behalf of the Tanzanian people for CFAES’s hospitality and the college’s willingness to advance Tanzania’s agricultural capabilities through Extension services. They said they looked forward to returning home to apply what they learned so that future Extension educators are equipped with the necessary skills to continue Tanzania’s agricultural development.

•

For more information, contact Dr. Erbaugh at erbaugh.1@osu.edu or 614-292-6479. Contact the writer, Beau Ingle, IPA program manager, at ingle.16@osu.edu or 614-292-4221.

Raising crane

Work continues on CFAES’s new Department of Food, Agricultural and Biological Engineering Building, located on the Wooster campus of CFAES’s research arm, OARDC, in this shot taken Feb. 11 by Ken Chamberlain of CFAES Communications.

Work continues on CFAES’s new Department of Food, Agricultural and Biological Engineering Building, located on the Wooster campus of CFAES’s research arm, OARDC, in this shot taken Feb. 11 by Ken Chamberlain of CFAES Communications.

Sustaining the Sahel: CFAES students gain international research experience (and more) in Senegal

CFAES graduate and undergraduate students have been part of a research project in Senegal since summer 2013, sponsored by the National Science Foundation Division of Biology within the Partnerships for International Research and Education (PIRE) project. (Pictured left to right are Matthew Bright, Spencer Debenport and Chelsea DeLay.)

CFAES graduate and undergraduate students have been part of a research project in Senegal since summer 2013, sponsored by the National Science Foundation Division of Biology within the Partnerships for International Research and Education (PIRE) project. (Pictured left to right are Matthew Bright, Spencer Debenport and Chelsea DeLay.)

Richard Dick, professor of soil microbial ecology in the School of Environment and Natural Resources (SENR) directs the $2.6 million NSF PIRE project that is focusing on the Sahel, where landscape degradation is causing desertification and seriously reducing food security. A potential solution involves two unrecognized native shrub species that can be intercropped to provide benefits to soils and crops while restoring Sahelian agroecosystems.

The graduate students are conducting research for about two years in Senegal on these shrub species that can coexist with crops in the Sahel. They are focusing on the microbiology of shrub rhizospheres and associated interactions with crops. This includes studying beneficial bacteria and fungi, particularly mycorrhizal fungi. These beneficial organisms can promote crop growth by producing plant hormones, improving nutrient status, and increasing drought tolerance and resistance to diseases.

“This research is important because it is developing fundamental principles to design microbiologically based cropping systems that reduce or eliminate external purchased inputs and increase crop yields using a locally available resource,” Dr. Dick said. “Such a system is critical and appropriate for subsistence farmers in the Sahel who have limited resources and are risk adverse.”

He further reflected on the compelling educational component, stating, “The project is providing Ohio State graduate students a unique chance to do cutting-edge research in a developing country and expand their cultural horizons. It also opens up new avenues for international opportunities and collaboration in their future career.”

We recently had the opportunity to catch up with the students and learn more about their research and their observations of living and doing research in Senegal.

•

Matthew Bright (pictured kneeling, with Spencer Debenport) is a second-year doctoral student in SENR specializing in soil science, advised by Dr. Dick.

Matthew Bright (pictured kneeling, with Spencer Debenport) is a second-year doctoral student in SENR specializing in soil science, advised by Dr. Dick.

Matthew is doing his dissertation research on the ecology of mycorrhizal fungi in these shrub intercrop systems, focusing on pearl millet, the staple crop of Sahelian farmers. Mycorrhizal fungi benefit crops by infecting roots; their hyphae significantly increase rooting capabilities and in turn promote nutrient and water uptake. He is investigating how the shrub Guiera senegalensis can promote mycorrhizal spore innoculum and infection rates of millet. He is pursuing the very novel mechanism that mycorrhizal hyphae can connect the shrub roots to millet roots as a means of transferring nutrients and small amounts of water to the millet plant. The results could provide a whole new strategy for reducing nutrient and drought stress for crops in the harsh semi-arid environment of the Sahel.

Matthew reflected that his time in Senegal has been far more than just a research experience. “Each time we go to a rural village to sample a farmer’s field, we have an incredibly enriching experience sharing a lunch with the farmers and their families, being helped with our sampling by the village boys, and learning about the rich cultural heritage of farming in Senegal,” he said. “In addition, I do my daily laboratory research in Dakar with Senegalese and French students. This has enabled me to learn French and how other countries conduct research.”

However, research in Senegal can be challenging, with frequent water outages in the lab as well as constant heat, humidity and bugs. He said, “I am very grateful for this opportunity to be here where I can be stretched to learn about international research, the culture and people of Senegal while conducting doctoral research on tropical soil microbiology.”

•

Spencer Debenport (pictured holding a millet plant, with Matthew Bright and local farmers) is a second-year doctoral student in the Department of Plant Pathology. His adviser is Brian McSpadden Gardener.

Spencer Debenport (pictured holding a millet plant, with Matthew Bright and local farmers) is a second-year doctoral student in the Department of Plant Pathology. His adviser is Brian McSpadden Gardener.

While in Senegal, Spencer is conducting research on beneficial bacteria and fungi of shrub rhizospheres and how that influences the microbial communities on crops grown in association with the shrub. This will include testing these organisms for their potential to improve millet growth and resistance to diseases and possibly drought. Additionally, he is surveying the extent of disease organisms on millet. He is using microbial community molecular and culturing analyses in order to identify potential plant growth-promoting microorganisms associated with millet plants growing with Guiera senegalensis.

“Once identified, we can use information about the ecology of those organisms to improve this intercropping system in Senegal,” Spencer said.

Reflecting on his time so far in Senegal, he noted that although there are challenges to doing research in Senegal, there are rewards that would not be possible if he was doing the research in the U.S.

“Working on a project like this in a developing country poses unique challenges with logistics and customs — including having to schedule in time to drink ataya tea with our cooperating farmers — but it is so rewarding to be able to conduct basic research that we expect will directly benefit the farmers of the Sahel.”

•

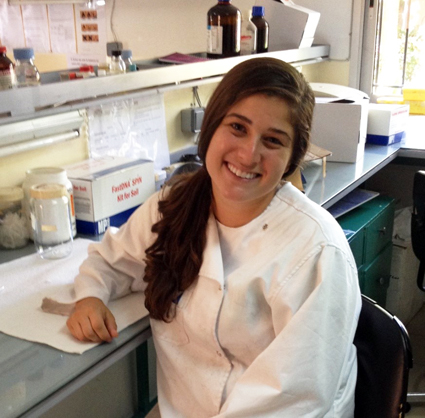

Chelsea DeLay (pictured in the Laboratory of Tropical Microbial Ecology of the Institut Sénégalais de Recherches Agricoles, Dakar, Senegal) is a soil science research associate in SENR under the direction of Dr. Dick.

Chelsea is investigating soil nitrogen dynamics of millet crops within and outside of shrub influence. In particular she is investigating whether these shrubs promote nitrogen (N) fixation by harboring microorganisms that can take atmospheric N and incorporate it into soils.

“Most of our samples come from farmers’ fields in various villages throughout Senegal, where we are always welcomed with open arms,” she said. “At the end of our sampling day, we are usually invited to eat and drink tea with the village chief.”

She reflected on the impact of the project, noting, “After spending so much time in the villages, I am much more aware of the positive impact this project can have for the Senegalese people, and I am very excited to see how our results can be implemented in the field.”

She also reflected on the experience personally and as a budding scientist: “So far my experience in Senegal has really taught me how to adapt to new situations, in both my work and personal life. Almost every day there is a new challenge I would not be faced with back home, whether it be working around issues in the lab or trying to bargain for the right price at the market. Communication is by far my biggest challenge so far, but most people are very patient with my French, and are persistent in trying to teach me Wolof, the native language.”

Despite these challenges, she said, “There has not been one moment I regret coming here.”

•

The project brings together French, African and U.S. institutions for the first time and includes Ohio State University (lead), the University of California at Merced; Central State University, Wilberforce, Ohio; Institut Sénégalais de Recherches Agricoles, Senegal; IRD, Montpellier, France; Laboratory of Tropical Microbial Ecology, Senegal; and the University of Thies, Senegal.

The NSF PIRE project, Hydrologic Redistribution and Rhizosphere Biology of Resource Islands in Degraded Agroecosystems of the Sahel: A PIRE in Tropical Microbial Ecology, is a five-year $2.6 million project. Dr. Dick is the project’s director. Co-investigators are Brian McSpadden Gardener, Department of Plant Pathology, Ohio State; John Reeve, Department of Microbiology, Ohio State; and Teamrat Ghezzehei, University of California at Merced. Additional components are a study on the hydrology of these shrub intercrop systems and a major educational effort that includes undergraduate internships in Senegal and two advanced training courses for early career scientists (U.S. and African) in tropical soil microbiology.

NSF’s PIRE program, instituted in 2005, supports international collaborations in research and education to advance scientific solutions to daunting global challenges.

Zero waste, big benefits: Compost course coming in March

CFAES’s research arm, OARDC, holds its 2014 Ohio Compost Operator Education Course March 25-26 in Wooster. The course is for people who work at or with large-scale composting facilities — places that handle tons of waste and compost, rather than bushels, at a time. Get the flier and registration form here. Register soon; five of the past six years have sold out (attendance is limited due to the hands-on nature of the sessions).

CFAES’s research arm, OARDC, holds its 2014 Ohio Compost Operator Education Course March 25-26 in Wooster. The course is for people who work at or with large-scale composting facilities — places that handle tons of waste and compost, rather than bushels, at a time. Get the flier and registration form here. Register soon; five of the past six years have sold out (attendance is limited due to the hands-on nature of the sessions).