By Brenden Wood

My grandmother was a heritage speaker of Polish, and I had always admired her ability to speak in another language. When I came of college age, I wanted to pursue Polish, but I was not able to during my undergraduate career for a host of reasons, the foremost being that it just isn’t widely taught. So, when I arrived to OSU last year to start my M.A. at the Slavic Center, I jumped at the chance to finally study Polish. I had studied Russian at that point for four years, and I was excited to be able to start in on a new Slavic language. Unlike with Russian, however, I had no career goal or aspirations with the language. The language is simply something that I have wanted to learn for a long time, and I am excited to finally have the opportunity to thoroughly explore the language. Therefore, when I had the chance to travel to Poland this past December, I didn’t hesitate.

Weirdly, I had no personal expectations for the trip. My family came from southeastern Poland, by Zamosc, but we have retained no connection with family in the area. My great-grandfather did not leave on happy terms. I did not have any glorious or romantic ideas to reach back into a forgotten past, and hopefully pull something forward. I figured that I would enjoy the journey, and see where it took me.

I toured Warsaw and Krakow and I went on an excursion to Auschwitz. Writing about what is there does not do it justice, but suffice to say that I did not walk away any more distraught or calmly than when I arrived. I instead got an unsettling sensation that I was a witness, and I felt a sense of odd displacement. It wasn’t that they didn’t make a great impression on me, quite the opposite. I think that it was more that I didn’t have any idea how I would feel after seeing these places, ravaged as they all were by history. It was easy to imagine that seeing Auschwitz would give me a sense of closure or understanding, but instead it just left me with a pensive feeling, as if I had left with more questions than when I had arrived. However, these questions now are still not clear.

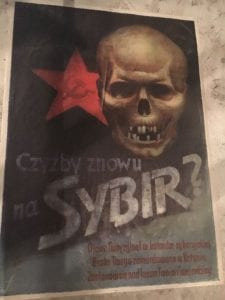

One particular event sticks out in my head as I attempt to come to terms with everything. I had the chance to sit down for a meal with relatives of a family friend who are natives of Poland, now living in the small town of Siedlec. As most know, Poland has had a difficult century in terms of political independence and stability. After being ravaged by the Third Reich in the 1940’s, Poland fell behind the Iron Curtain, and was subjected in many ways to the authority of the Soviet Union. Sparing everyone the well-known history lesson here, I’ll just say that as a result of this political situation, learning Russian became mandatory, which is what brings me back to my curious dinner in Siedlec.

My host and hostess both spoke broken English, but each commanded a decent vocabulary and passive understanding of the language. My host spoke excellent Russian, while my hostess had a better command of English. Naturally, they both spoke Polish pretty well. My command of English is that of a native, and my abilities in Russian, although by no means native, are not paltry. My Polish is definitely more primitive, but I can communicate and understand. What ensued over dinner was a conversation in a mixture of three languages, a conversation which conveyed to me sadness, anger, fear, but, above all, great pride. My hosts love their country dearly, and are proud of all that has happened there. What was odd for me, was that I understood the events we discussed not as a student of Poland, but as somebody who has long studied Russia and the Soviet Union. When at a loss for a word, my host and I would revert to Russia to clarify a word, while I would revert to English with my hostess. It was a bit disconcerting to use Russian at the table, as it clearly made everyone a bit uncomfortable. My hostess did not retain her knowledge of the language, and it clearly had been something that she had not made a point to remember. My host, who used Russian at work, had been forced by the nature of his profession to retain a technical command of the language. However, it clearly made him too uncomfortable to have to rely on Russian with me when we were all at a loss for words.

Probably the most interesting takeaway from this pleasant dinner was when we discussed how things had changed in Krakow. They told me that prior to the 1990s, Krakow had fallen into disrepair. They were not specific as to why the city was allowed to literally crumble, but it was clear that it was the result of a lack of funding and motivation under the communist regime. The answers are clear: feeling trapped by communism, the Poles were more focused on survival than maintaining the city and allowing the communists to enjoy the beauty and pride of Krakow. What was a bit perplexing was that the people of Krakow, who so clearly loved their city, allowed it decline to the point of shame leading up the 1990s, but immediately began to rejuvenate the city once Poland was once more democratic. The people of Warsaw had leapt to repair Warsaw after the war, even though they were at that time falling under the yoke of communist rule. This perhaps seems as if I am running circles around something with a clear answer, but I still pause and think. The anger toward the communists and the Soviet Union was tangible from the conversation, but so too was the pride at how Krakow has been revived. What is unclear to me is how this pride was maintained as a beacon and hope for all those years, but now seems to render itself both positively and negatively. It is positive in that they revived a beautiful city rich in history and culture, but negative in that this beauty is now viewed as a reminder of vindication for decades of being wronged. That is at least how it is seems to a humble foreigner.

I am still mulling over a lot of what I saw and discussed with people when I was there, but I nevertheless keep returning to that unsettling sensation I got while there. As I said, I felt a witness in a distant way to everything that has happened there. I see the logic and reasoning behind the fear, anger, and sadness. I also understand the pride. Being a student of post-Soviet space, I understand the importance of historical memory, and the difficulty that it poses to each individual. It was odd to be connected to Poland by blood, albeit distantly, but to understand it better through the lens of the Russian language and post-Soviet politics and memory. It was a very interesting trip, and I look forward to return.