Isabel Richards, Veterinary Science – South Africa and owner/operator of Gibraltar Farm

(Previously published with the Eastern Alliance for Production Katahdins (EAPK): February 28, 2022)

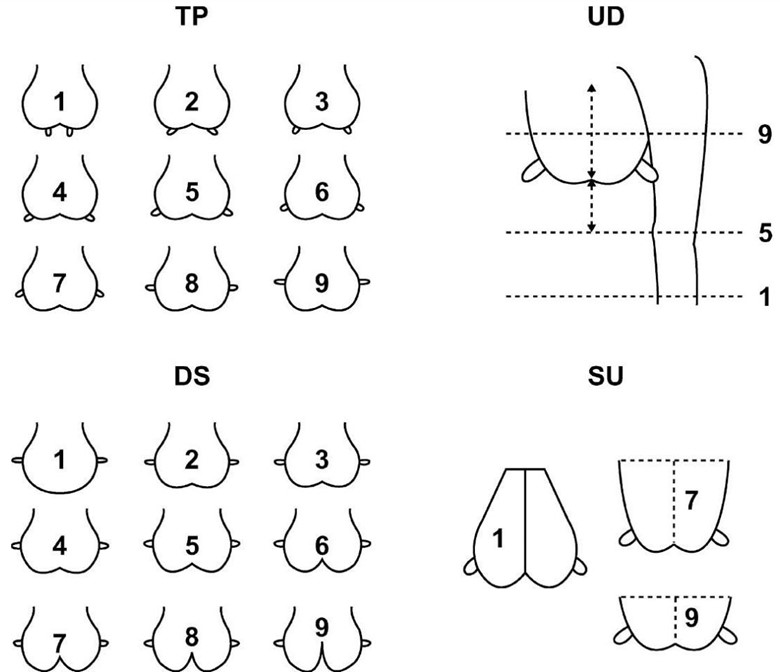

(Image Source: Alba et al., 2019)

Ewes only have two teats and hopefully raise at least twin lambs, so maintaining healthy udders and culling ewes with udder problems is important to minimize lamb losses and bottle lambs while ensuring optimal growth of lambs on your farm. Mastitis leads to lower weaning weights in lambs of affected dams, takes time and money for treatment, as well as slowing down genetic progress due to forced culling of ewes. Rates of mastitis are variable across different farms. It is important to keep track of the percentage of ewes that get mastitis each year or are culled for lumpy udders or poor milk production. You can then intervene as soon as you start seeing an increase in cases, and can track the success of interventions if you do have an issue with mastitis on your farm. Management as well as genetic selection (udder conformation) can also be used to improve udder health in your flock.

Mastitis

Mastitis is an infection/inflammation of the udder and can be either clinical (you see abnormal milk, swollen udder, sick ewe) or subclinical (milk and ewe look normal but you can culture bacteria from milk, there are white blood cells in the milk and lambs just do not grow as well). If you are seeing a lot of mastitis on your farm or if you are starting to see increased rates, it is important to culture milk from affected ewes so you can get a better idea of how to best manage the problem.

Clinical Mastitis

Mild – You strip milk out of the udder and it looks abnormal (chunky, gray), but there is no swelling or redness of the udder and the ewe looks perfectly normal. You are probably checking this ewe because you caught her lamb stealing. This will likely progress to more severe disease if you do not intervene. It is important to empty all the milk out of these udders multiple times a day as you are removing bacteria along with the milk. The longer bacteria sit in the udder the more they multiply and increase inflammation. Inflammation is damaging to the milk-producing cells and the more inflammation associated with mastitis the higher the impact on milk production for the rest of the ewe’s lactation. Intramammary infusions of antibiotics work well but need to be instilled into an empty udder to work properly. There are no intramammary antibiotics approved for sheep so this is extra label use. Make sure to consult with your veterinarian for proper use.

Moderate – The ewe’s udder looks abnormal, red, and swollen. The milk is abnormal but the ewe does not have a fever. You either noticed the abnormal udder, noticed her lamb stealing, or noticed the ewe limping on a rear leg. It is still very important to empty the udder. Antibiotics and anti-inflammatory medications are needed. This can be treated with intramammary or injectable antibiotics. Once again, be sure to consult your veterinarian as there are no antibiotics approved for sheep specifically for mastitis. You are likely to see a decrease in milk production for the rest of the lactation if disease progresses to this point before you start treatment.

Severe – The milk and udder look very abnormal. The ewe has a fever and she is sick. You noticed a sick ewe, she is probably limping or unwilling to get up. These ewes need aggressive treatment or they will die. The worst case of this is gangrenous mastitis (blue bag) where toxins produced by the bacteria cause blood clots in the vessels supplying the udder and parts of the udder die. Parts of the udder feel cold and the skin is pale, blue, or purple and can extend onto her belly. If the ewe survives the initial few days, she will get better but the affected part of her udder will eventually slough off, usually taking weeks or months to heal. During this time, she will be susceptible to fly strike and have an open wound where the dead tissue separated from the rest of her udder. She will likely not have milk for the rest of this lactation and only the unaffected part of her udder will be available to produce milk in future lactations. On my farm I will treat ewes aggressively for a day or two to see the extent of her udder that is affected and unless it is a really small area, I will humanely euthanize her.

Subclinical Mastitis

This has been studied extensively in dairy animals but few studies have been done in ewes that suckle lambs. Somatic Cell Counts (SCC), California Mastitis Tests (CMT), and milk cultures are used to quantify this. SCC measures the numbers of white blood cells in milk and has to be done in a laboratory. In general sheep have higher SCC than cows, but levels higher than 400,000 are generally accepted as indicative of mastitis. A CMT can be done on-farm. A small amount of milk is mixed with a reagent and a gel forms if there are a lot of white blood cells in the milk. CMT is scored from 1+ to 4+. In sheep, a score of 3+ or higher indicates mastitis. Milk cultures are done in a lab where the milk is incubated on bacterial growth media. Healthy milk should be sterile and will not grow any bacteria. It appears from multiple studies that a lot of ewes that suckle lambs have positive milk cultures, even if they do not have high SCC or positive CMT tests. Ewes older than 5 years had 13% higher SCC than younger ewes in one study.

Subclinical mastitis is important because these are the ewes that you never notice a problem with, but if you palpate udders before breeding, they have lumps or hard udders. They might just lamb with non-functioning udder halves or all of a sudden have a year where their lambs do not grow as expected. Studies have found that ewes with lower SCC reared heavier lambs. A study at MSU found that ewes with 500,000 SCC reared lambs that were 10.6 pounds lighter than ewes with 100,000 SCC. Selecting for good udder conformation and having good mastitis prevention management should help to reduce subclinical as well as clinical mastitis.

Udder Anatomy and Udder Scores

Udder Anatomy

The udder is composed of milk producing tissues as can be seen in the figure above. Surrounding and interspersed within this tissue are fat, blood vessels, lymphatic tissue, nerves, and connective tissues. A normal udder feels soft and looks symmetrical.

Having a bout of mastitis can severely affect a ewe’s milk production. If a lobar duct is blocked by a blood clot, pus, or swelling due to inflammation, the whole section of udder drained by that duct will dry off as the milk that is produced there cannot exit the udder. The buildup of pressure will cause those alveoli to stop producing milk. If you do not milk out the ewe that you are treating for mastitis the same thing will happen in the whole udder.

Ewe lambs are born with well-developed cisterns and teats as well as some of the larger ducts. But most of a ewe lamb’s alveoli and interlobular duct development occurs during the first few months of life, the majority happening when a ewe lamb is 2-4 months old. The fat and connective tissues of the udder develop at the same time. Overfeeding during this time can lead to preferential growth of fat and connective tissue in the udder over milk producing tissues. Two studies have found that a lower growth rate in ewe lambs between 4-20 weeks of age was associated with better milk production during their first lactation.

Udder Conformation

A lot of research on udder conformation has been done in dairy sheep to find the best conformation for milking. Ewes that suckle lambs have different considerations since they are “milked” by the lambs much more frequently than dairy animals so they do not need to store large volumes of milk. Milking machines require different teat placement than what is ideal for suckling lambs. There are certain udder conformations that predispose to mastitis in dairy animals that are equally applicable to ewes suckling lambs. Udder conformation is heritable so selection can be used to minimize mastitis risk.

Udder Depth (UD)

Udder depth (UD) is the distance between the udder cleft (where the suspensory ligament pulls up the udder in between the two halves) and the body wall. A score of 5 is where the udder cleft is in line with the ewe’s hocks, a score of 1 is a very low hanging udder that is close to the ground. Ewes with udder scores lower than 5 (udders that hang down lower than a ewe’s hocks) are more prone to mastitis. A study in the UK found that for every cm (⅖ of an inch) increase in UD a ewe’s Somatic Cell Count (SCC) increased by just under 10%. Selecting against deep udders can have a protective effect against mastitis. In dairy sheep there is a negative correlation between milk yield and UD because a ewe has to have a large udder to store large volumes of milk since she is only milked once or twice a day. This correlation should not be a problem for ewes suckling lambs as they only have to store milk for an hour or two at most as their lambs drink small amounts frequently throughout the day.

Teat Placement (TP)

Teat Placement (TP) is the distance between the lowest part of the udder and where the teat attaches to the udder and is scored on a scale of 1-9. Teats attached to the lowest part of the udder that hang straight down are scored as a 1, while teats attached above the widest part of the udder that point straight out to the side are scored as a 9. The ideal teat placement for ewes suckling lambs is a 5 (as can be seen in the “Anatomy of the Udder” picture above). A study in the UK found that ewes with TP scores of 5 weaned the heaviest lambs when compared to ewes with lower or higher TP scores. They also found more bite wounds (from lambs) on teats of ewes with TP scores higher and lower than 5. The lower the teat placement is on the udder, the easier it is to fully empty the whole cistern when machine milking. Ewes with TP-1 udder scores are great for milking machines but it is harder for lambs to find these teats and they have to bend them out (kinking the teat cistern and decreasing milk flow) in order to drink. TP-9 udders are hard to empty for machine milking as well as for lambs. These teats are also hard to find as they sit right against the ewe’s inner thigh. Chafing and teat irritation are also a problem with teats in this area as they constantly rub against the ewe’s inner thigh, unless she has a pendulous udder.

Degree of Separation (DS)

The suspensory ligament is very important. It functions to keep the udder close to the body wall and prevent mechanical trauma to the gland and teats. A strong suspensory ligament keeps the udder from swinging side to side and bumping against the ewe’s legs when she walks. The depth of the cleft between the two udder halves is an indication of the strength of the suspensory ligament. The Degree of Separation (DS) between the two udder halves is used to measure this. More separation is better, so 1 is the worst score and 9 is the best. The deeper a ewe’s udder depth (UD), the more important a higher DS score is.

Degree of Suspension (SU)

Degree of Suspension of the udder (SU) is the ratio between the width of the attachment of the udder to the body wall and the Udder Depth (UD). Wider attachments are better as they make for a more stable udder with less risk of trauma. A score of 7 is a square udder with the same depth and width, a score of 1 is undesirable and more prone to mastitis.

Teat Size

Teat size is also important. Ewes with shorter and narrower teats are less prone to mastitis. Lambs have trouble suckling from very thick and long teats. A UK study found a 7.2% increase in Somatic Cell Count for each square cm (0.155 square inch) increase in teat size.

In summary, selecting for ewes with UD of 5 or higher, TP score of 5 or closer to 5, higher SU scores and higher DS with shorter and smaller teats should lead to less mastitis and better lamb growth.

Management for Improved Udder Health

Environment

The bacteria that commonly cause mastitis are found on the skin (Staphylococcus and streptococcus), GI tract (E. coli), and respiratory tract (Mannheimia and Pasteurella). Having dry, clean bedding or pasture for ewes to lounge on decreases the exposure of udders and teats to bacteria. Poor bedding quality with a buildup of ammonia predisposes lambs to pneumonia. The bacteria causing pneumonia can infect their dam’s udders when suckling.

Rates of mastitis are lower in ewes on pasture when compared to ewes in confinement. Barns that are bedded more frequently leads to reduced rates of mastitis. Wet bedding offers a good environment for bacteria to grow so keeping bedding dry is very important.

Prevent Lambs from Stealing Milk

In non-dairy flocks, stealing lambs are one of the biggest spreaders of infectious mastitis in the ewes. An affected ewe’s lambs suckle from her, but she kicks them off and because they are still hungry, they then try to suckle from other ewes. Even if they are not very successful at it, they can deposit the mastitis causing bacteria on a large proportion of the other ewes’ teats. When you see lambs stealing, check their dam’s udder and separate her and her lambs from the flock to minimize transmission. Bottle feed the lambs if needed. If the milk is not very abnormal, the ewe allows the lambs to suckle and they are willing to drink, keeping the lambs on the ewe can help a lot during treatment as removing milk helps to flush out the bacteria and inflammatory cells. Milking out the ewe multiple times a day is necessary if her lambs are not doing the job.

Ewes with teat injuries will prevent their lambs from drinking. Look for chafed skin, skin infection, or soremouth lesions on teats. Treat appropriately and isolate her and her lambs until you are sure that she is letting the lambs drink. Bottle supplement the lambs if needed.

Ewe Nutrition

Inadequate protein and energy during gestation as well as inadequate energy during lactation has been associated with higher rates of mastitis in ewes. Ideally ewes should lamb in at least a body condition score (BCS) of 3 for optimal milk production. Lambs are more likely to cause trauma to a ewe’s udder if they are hungry, and thinner ewes tend to have more traumatic teat injuries from lambs biting them. One study found that lambs reared by a ewe in a BCS of 3 were 2.86 pounds heavier than lambs reared by a ewe with a BCS of 2.5 or lower.

Clinical mastitis, where you see a sick ewe with a visibly abnormal udder and milk, is not the only issue to watch out for. Subclinical mastitis, where you may not notice any abnormality in the ewe but her lambs do not grow quite as well as in previous years or you notice asymmetry of her udder or feel lumps at dry off or pre-breeding udder examination, is equally important.

Vaccines

VIMCO mastitis vaccine is available for goats in the U.S. It is a vaccine against Staph aureus and Coagulase Negative Staph (CNS). It was developed for dairy animals but can have its place on farms with problems with these specific bacteria (in addition to management changes). It is off label use to administer this vaccine to sheep so you will have to work with your veterinarian.

Anecdotally, farmers have found that vaccinating their lambs and pregnant ewes against pneumonia has led to fewer cases of mastitis.

Culling Ewes with Mastitis

Ewes that have mastitis in one lactation are more likely to have mastitis in subsequent lactations. Bacteria like Staph aureus can form small abscesses that protect the bacteria from antibiotics and can be very resistant to treatment. If milk cultures identify Staph aureus, culling is recommended to prevent spread throughout your flock. In cows they recommend culling heifer calves out of cows with Staph aureus (if they drank colostrum/milk from the cow) as they have found that they can be infected through consuming the milk and then calve already infected with Staph aureus. Flocks that do not cull for lumpy udders tend to have an increase in rates of mastitis.

Dry Off Management

If you leave lambs with their dams, the ewes will eventually stop producing milk naturally. The more milk a ewe is producing at the time of dry off, the greater the chance that she will develop mastitis. Studies have found a decrease in mastitis when lambs are weaned at 120 days vs 60 days. If you are weaning early and feed ewes concentrate, it is recommended to stop the concentrate about 7 days before weaning. A waxy plug forms in the teat opening shortly after weaning which prevents organisms from entering the udder and causing mastitis. It is best to not disturb this plug between dry off and the next lambing.

A study in the UK looked at the effects of applying a dry cow treatment to ewes at dry off to see if it could help cut down on mastitis in the next lactation. They treated half the flock and kept the rest as a control. One farm had low rates of clinical mastitis and they looked at Somatic Cell Count and milk cultures during the next lactation. They did not find a significant difference in the incidence of subclinical mastitis in treated ewes. The other farm did have high rates of clinical mastitis and they did see a significant reduction in mastitis in treated ewes, although the treatment did not prevent all cases of mastitis. They looked at the cost of treating the ewes and the savings due to ewes not getting mastitis and found that the reduction in mastitis was not worth the cost of the dry off treatment.

OPP

Ovine Progressive Pneumonia is a viral infection that can cause hardbag – udders that look full but are hard to the touch and do not produce milk. Other causes of mastitis can cause similar signs and testing ewes with these symptoms for OPP (a blood test) can help you identify this problem if it is present on your farm. If you do find ewes that are positive, a whole flock testing program can give you an idea of the prevalence in your flock. OPP can be successfully eradicated by a test and cull program.