Postcolonial Shakespearean Journeys, Zimbabwe and England

Keywords: Zimbabwe, South Africa, Two Gents Productions, Shona, Two Gentleman of Verona, Translation, The Moors, Non-Binary, Identity.

Interview audio

Published on 26 September 2023.

Tonderai Munyevu

Christopher Thurman

Interview transcript

Introduction

Amrita Dhar

Hello and welcome. My name is Amrita Dhar, and I am the Director of the project Shakespeare in the “Post”Colonies which is hosting a series of interviews with postcolonial Shakespeareans from around the world. In today’s conversation, our invited collaborator Professor Christopher Thurman of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg speaks to the Zimbabwean-born and British-based actor, writer, and director for theatre, screen, and radio, Tonderai Munyevu.

Conversation

Christopher Thurman

My name is Chris Thurman, I am the director of the Tsikinya-Chaka Centre at the University of the Witwatersrand, in Johannesburg, South Africa. Our centre supports research and practice, if we can, at the point of intersection between Shakespeare and transnationalism and multilingualism. And an artist whose work very productively benefits from that intersection is Tonderai Munyevu, who is, I’m very proud to say, an affiliate member of our centre. And so, without any further ado, I am going to ask Tonderai to give him, unfairly, a sentence or two to introduce himself. And then we will spend some time unpacking all of the details around his life and work. Thanks, Tonderai, over to you.

Tonderai Munyevu

Thank you so much. Yes, my name is Tonderai, as you said. And I trained as an actor, but I am a writer, and a director, as well as an actor. And one of the things that I always try to make sure that I say, especially to those who are listening, who are interested in making their own work, is that actually, beyond being an actor and a writer and a director, I would also say that I’m a producer. There’s quite a lot of work one has to do… is to put it all together, so that one has work that one can produce. So yes, I’m an actor, writer, producer. I’m particularly interested, obviously, in my own background as a Zimbabwean person who was brought up in England, about that intersectionality of culture. But also identity, which I think when we work with Shakespeare, we sort of have permission to explore. Because people feel that they know the stories already, and they just want something interesting about those stories.

Christopher Thurman

Fantastic. Thank you so much. You mentioned an interesting… I guess we could call it national or bi-national identity, and I’m sure this is a point of frustration to you when you are presented or when your work is discussed. Although of course, it’s also a very constructive nexus in your work. But can I ask you just to tell us a little bit more about how you see yourself either as a, what could we call it, a member of the Zimbabwean diaspora, or as a British African, or an African British person, or as a Zimbabwean in exile? These are the sorts of, you know, slightly dissatisfying labels that people will use when they’re when they’re trying to provide a synopsis or a location for your work geographically or imaginatively. But do you have any thoughts on that?

Tonderai Munyevu

Yes, I suppose it’s some of the things that you’ve run through. Ah, identities that at some point, I’ve tried out, you know, as a creative person. [laughs] Am I a Zimbabwean in exile? Why? What would that mean creatively for me? So, mentioning the different labels… I sort of feel like I’ve gone through that in my own life. Because let’s say if I said I was a Zimbabwean in exile, that would make my work sort of a bit more political, more exciting, I suppose. But it would also route me into a conversation with Zimbabwe and the politics of Zimbabwe, which I think my work goes beyond. If I was to say I was a Black, British Zimbabwean, I think it would place my Britishness into focus in a way that I don’t find in my work actually, despite having gone to university in England and having trained in England. So, those labels, when I hear them described, when I hear them mentioned outside of myself, I do find that that’s actually more to do with the world and where we are in defining ourselves, as opposed to what they say about me.

Having said all of that, one has to label oneself, and I think as I’ve grown as an artist I’m particularly proud to be a person who has a global outlook. A person who really feels that the stories they tell are not local. Yet, they come from a local perspective in some ways. So, I can speak from a Zimbabwean perspective. I can speak from the perspective of being a Black African British person, but who has an understanding really of Africa, in a way that some of my colleagues who are Black, British Africans have no understanding of Africa in a profound way that is based on their own experiences. So yeah, it’s a labeling game. And as you can tell with this answer, it’s a process. But I’m very, very proud to be a diasporan Zimbabwean, I must say, because I suppose when one is labeled that, there’s an understanding that you have a vitality about you, that you have a reference of many cultures, if not two, you know, you have more than that, potentially. And also, that you are somehow emblematic, you know. So, I like the idea that Zimbabwean person might look at me and say, yes, that’s a figure that I might tag along to, whether it’s the gay side of things, or the artist side of things, or the writing side of things, or the Shakespeare side of things. So that’s the most exciting at the moment.

Christopher Thurman

That’s wonderful, and very much… identity… what’s the word, the set of considerations that kind of opens up rather than closes down?

Tonderai Munyevu

Yes.

Christopher Thurman

I wonder if, given that many people who are listening to this interview might have some slightly clearer frame of reference for your location in the UK, than, for example, what it is like to encounter Shakespeare in Zimbabwe, or via Zimbabwe… And although you’ve talked about the challenges of being representative or emblematic, I wonder if you could tell us a little bit about your sense of how, either your own experience, your formative experiences of Shakespeare might differ from or be similar to something like the typical kind of educational encounters with Shakespeare in Zimbabwe? I ask that primarily because one of the concerns of this series of interviews is to think about the ways in which Shakespeare is encountered in educational settings in the global South of the postcolonial world. So, do you have a sense of, of being representative in that way?

Tonderai Munyevu

Well, I think I am representative, because I think when we were growing up in Zimbabwe… I left Zimbabwe when I was twelve, in 1996, and up until then, it felt to me that Shakespeare’s language was far more in use in day-to-day life than I found when I moved to England. So, I suppose because in Shona, which is the Zimbabwean language that I speak—we have many, Shona happens to be probably the most spoken in Zimbabwe—because we have proverbs, and sort of a natural tendency to poetry in our communication, I retrospectively realized that a lot of Shakespearean language that I knew was because people were using it in day-to-day use. You know, “all that glitters is not gold” or this fantastically wonderful, elaborate English, sort of poetry-based words that we didn’t know were Shakespeare, particularly when we were using them. So that was my first real encounter with Shakespeare at a very young age. But also always having, whether it’s Julius Caesar, King Lear, particularly the history plays just always available in the library is something that I think is powerful to think about, because of the fact that Zimbabwe is, was, is socialist when I was growing up, particularly with Mr. Mugabe as President. In a way that’s very different to when I came to the UK, and, you know, it was a required text that you sort of had to suffer through. So, there wasn’t a joy in the discovery of it. You had to do it. And you had to do it to a certain standard. You had to do it suddenly for GCSEs. And then you had to do it for A Levels if you did English. And so, there was a sense of obligation towards it. And I think I kept my love of it, partly because I could look at it through a Shona landscape, through a Shona framework. Especially King Lear. I remember at A level looking at that as a father dividing his kingdom, between his daughters and what that would mean. Suddenly, it meant that he was doing something terrible and unusual and something bad would happen as a result, because that’s what it would mean in my culture. So, I think that’s really the journey of it for me. Far more joy, I think, in terms of his language, when I was younger.

Christopher Thurman

Thank you so much for that. And it’s a useful reminder, and I think that might become a theme or a sub-theme in these interviews, that when we think about Shakespeare in the postcolonies or the global South, it’s not automatically an encounter of antagonism or clash. And that as you point out, the received wisdom would be that, you know, Shakespeare in the UK might be closer to or more accessible to those growing up there and studying. But in fact, as you point out, the kind of collective heritage that you could grow up in and enjoy as a young person in Zimbabwe facilitated that joyful encounter with Shakespeare rather than the schooling encounter in the UK. So that’s a very neat subversion there of some of our assumptions.

I wonder if we could talk a little bit more, skipping from your kind of formative years towards your professional identity, if we could talk about your affiliation with, or your founding of, Two Gents Productions, which would be something that a number of people might know you for, would associate your name and your work with. Of course, people who are listening to this interview might not know the full backstory of that.

And that’s a useful way for us to talk about some of your Shakespeare work. The two gents of Zimbabwe being the two gents of Verona: Two Gentlemen of Verona. And of course, Vakomana Vaviri Ve Zimbabwe, the production that was staged at the Globe as part of the Globe to Globe Festival in 2012. Um, um, so, tell us a little bit more about where that that came from: some of your collaborators and your own role in the project.

Tonderai Munyevu

So, Two Gents Productions was really three people. And the first person really was Arne Pohlmeier, who is German. But he had spent time in South Africa, actually. He was leaving South Africa and going to the UK. And he wanted to see if he could put together a company. And somebody had suggested that actually, a Shakespearean thing might be useful. And to do that in the tradition of the two-man Apartheid-era South African show would be interesting. And so, he came to London and asked around, really. So he asked around amongst other South African and Zimbabwean people that he knew who he could work with. I had just graduated from drama school at that point, and I certainly was hoping to be at the RSC [Royal Shakespeare Company] or somewhere else. And Arne came to me, and I just liked the idea of doing something and not waiting to be invited into a creative process. So, I remember that being the very first sort of combination was Arne and myself. And then a gentleman by the name of Denton Chikura joined us and we created Two Gents, really. And Arne had already selected Two Gentlemen of Verona as a play. And he thought that, you know, that would work particularly well, because it was Shakespeare’s sort of first play, and had wonderful duologues within it. So, it would solve the problem of having two men to do it. But there was enough complication in the broader, bigger scenes that he thought could be quite fun to watch.

And so it began, you know, and it was a really extraordinary time in my life because, you know, I certainly had a, an interesting journey with my own gender, which I felt got sort of, got aided by Two Gents because I could play women particularly well, and I enjoyed that. And so, it alleviated some of the pain that I felt that I wasn’t man enough for the industry, and that I didn’t look, you know—I was very, very, very androgynous at that point—and I didn’t look the way that would make me castable. I mean, thank God, the world has changed massively. And so really, it was the most fertile creative time that I’ve had certainly, in the sense that we started making work, and we started touring almost immediately. And then we had to make more work as we toured, while also growing up as people in our twenties, in a world that was very rapidly changing. And so, by the time we got to the Globe, that was indeed the combination of many, many years of hard work and tenacity. But also, we found a clarity of language, of theatrical language about what our work was, you know, we started to understand that yes, we originated with the Apartheid-era two-man show as inspiration, but that we really combined our particular interests, Denton’s interest in comedy, just pure, Charlie-Chaplin-esque comedy, beautiful comedy that was not political, and my need to explore my gender and to explore some sophisticated ideas around what I thought was what theatre could do, which I wasn’t seeing at that point. And Arne’s, just, energy of saying, “Well, if you want this done, let’s do it. We’ve got three weeks, let’s do it. ”

And so, it was a remarkable time. And by the time we got to the Globe, it felt suddenly that we knew who we were as artists, as diasporans. But also, that we combined all those different influences and elements into something really, really, really, really, really powerful. And to top it all off, you know, we were able to perform in our language, in our mother-tongue. Denton and I are both Zimbabweans, and we were able to perform for the very first time in our lives in Shona, which, as you know, is a beautiful language. And we found someone to do an extraordinary translation of it. And, I mean, that was transformative. I think I am what I am now because of those performances at the Globe. They just reached down in my soul, something much more operatic and, and far more human.

Christopher Thurman

Thank you. That’s a really moving account and generates some astonishing insights. I wonder if we could perhaps just stay on the subject of language for a little bit. Could you tell us a little bit about the… I don’t want to suggest a kind of order of priority or even a sequence… But something about the translation process? Because I think it’s very interesting that you describe the work itself developing around your own kind of expanding theatre practice. Was the process of translation kind of tied to that? Was there a corollary? Was there an increasing amount of Shona in your experimentation, and that developed into the production? Or was there a script that had been written that you then performed? I suppose I’m interested in that relationship between theatre practice, and maybe extemporaneous, spontaneous translation, as opposed to scripted translation.

Tonderai Munyevu

I mean, the spontaneous translations were from the very beginning, because we were very lucky. We had, you know, our director was white and German, so that immediately placed him in a position of being an observer, or as he likes to call it, a witness. And because he was in that position, we were able as two performers who share the same language and culture, we were able to experiment with how far we could go without being understood. Because somebody in the rehearsal room would be like, “Well, I don’t understand what’s going on.” But sometimes we’d push it so that his lack of understanding was actually part of our process. So, he, meaning him, standing in for the audience… The audience’s lack of understanding became part of what we were trying to actually do. We were trying to play with those dynamics of: what does it feel like to not understand for a while? And two things about that. The first was quite organic, that we, you know, Arne our director had always said, “Look, if this situation was in Zimbabwe, what would it be like?” You know, and we’ll be like, “Well actually, Lucetta and Julia’s conversation would be, yes, mistress and servant, but actually Lucetta would have a power of her own because, the, Julia would rely on her completely, you know, if this was a Zimbabwean setting. Julia wouldn’t know how to cook or run the bath by herself, you know. [laughs] So, the power dynamics will be very different.” And so immediately that led us into improvisation. And when we went back to the Shakespearean aspects of it, we of course, kept any of the things that Denton I thought were particularly juicy to perform, which the audience wouldn’t understand in terms of language, but they would understand in terms of how it made people feel, you know, especially the humour of it would be incredible.

And the other example, which was a bit more when we began to understand what we had and wanted to explore that further. We, in our Kupenga Kwa Hamlet [The Madness of Hamlet], we really felt that the Dido and Aeneas moment, that we could just do completely in Shona. And I remember we had to test that. And go “Okay, how much can we communicate?” I mean, how much is he saying? And there were long, long discussions about it. And ultimately, we just did a whole chapter of the play in Shona.

But what was extraordinary about that was the amount of pain that we could understand that the narrator ended up in by virtue of having to tell the story in Shona that was just this deeply, profoundly guttural way of expression, really, which in English you wouldn’t have. So that became actually… Shona gives you a certain set of performance elements that you just wouldn’t get. It’s a very onomatopoetic language, and you can do a lot of vocal tics that you just wouldn’t be able to make work in English. And you could be, actually, allowed or propelled into far more emotion than you are in English. So that in Shona, when you’re telling a story, and there’s an emotion required, you actually have to do that, that emotion. [laughs] It’s part of the responsibilities of the language, is you have to say “That woman cried,” you know [crying noises], “she cried,” you know. Because if you said, “That woman cried, she cried,” it just doesn’t communicate anything. People would be quite confused about what you’re doing or saying.

So, by the time it got to the Globe, there was an invitation from the Globe, whose whole point for the Globe to Globe was to say, “we want Shakespeare in all these languages.” And so, we had to commission an official translation. Which when we received in rehearsals, we were blown away. Because, of course, the depth of the language in Shona is not colloquial Shona. So, we had to go through the process that English people do when they are performing Shakespeare, of asking, “What does this mean? What does that mean? What does this mean?” And as people who hadn’t, I mean, I hadn’t grown up in Zimbabwe, so I to do a whole other journey of, you know, “What’s the Shona word for snow?” for example. And so, we were reading it and coming to terms with ourselves and humbling ourselves as well, to try to honour the language. And when we did, yeah, it was an extraordinary experience. I’ll never forget it.

Christopher Thurman

Mm. You’ve talked about the benefits of misunderstanding, or lack of understanding, or the challenges that can help an audience to obtain new insights if they don’t always follow the language directly. And in your case, as a performer, the challenges that come from encountering a not entirely familiar language or a particular dialect or register of the language that was a challenge to you, even as a Shona speaker. But I guess this brings us to an interesting and perhaps slightly painful nub, which is the question of audience and what one I suppose has to imagine would be touring these productions around Zimbabwe, and how audience responses might be different when there’s a familiarity assumed in all audience members, as opposed to, perhaps, you know, some Zimbabweans that you might have in a London audience, responding to the language with not just understanding but with on a, an intuitive level. I mean, do you have any further thoughts around that? Or am I making too much of that issue?

Tonderai Munyevu

Well, I mean, in Zimbabwe everybody understands both languages, which is great. But I do remember performing, I think it was Two Gentlemen of Verona, in English in Zimbabwe, in Chitungwiza, outside of the areas that we were traditionally performing in, i.e. white areas or white festivals, you know. Not necessarily white as in, they’re produced by white people. It’s just that audiences in Zimbabwe tended to be white because they, for various reasons, partly to do with money, but partly to do with the culture of theatre, as is said in this way, theatre is a middle class, Western sort of number, you know. And those problems, they extend across the world, and they certainly do in Zimbabwe and in Harare. So, I remember particularly us being dissatisfied with that, and wanting to go into the townships, for want of a better phrase. And we went to Chitungwiza. And we decided to perform Two Gentleman of Verona there. And, I mean, people were just incredibly bored, [laughs] just completely bored. And it was extraordinary, because we had had quite a lot of success. So, we were quite like “What’s going on?” And one of the things that we did just very, very naturally, was to just start translating the play on the spot. And we just kind of translated it on the spot, and sort of improvised it, and kept the story going. And it did have a response from the audience. And I remember that particular performance, because when we finished, people were very grateful. But I remember there was a movie that was coming on, not a very good one, but you know, some sort of film that was made, and it was in English, and everybody went silent and watched it. And that taught me something about theatre, that there was a way in which the audience was told a certain way of behaviour was expected.

But I don’t think for the film, they had to be told that a certain form of behaviour was expected. Because everybody somehow knows films. And theatre, somehow people were so grateful that we were there, that they sort of trained the audience. And you know, and had the audience not been trained, I think they would have just gone, they’d have, you know, people would have gotten up during the thing and walked away, or, you know. And certainly, some of them tried to do that. And that was frowned upon. And that affected the performance. Because again, it was “Is this a human experience? Or is it something else?”

Christopher Thurman

Hm.

Tonderai Munyevu

You know, because if it’s a human experience, I interact with it. If it’s not, I watch it. But then, why are you here? [laughs]

Christopher Thurman

Hm.

Tonderai Munyevu

I can just watch the film. And so, I remember that about language, how now we were wrestling with it. But actually theatre itself creates its own language that is tricky to navigate.

Christopher Thurman

Hm. That’s fascinating that it’s not, as you say, not just the linguistic language issue, but the medium as a kind of language as well.

Tonderai Munyevu

Yes.

Christopher Thurman

Now, I know that I will be in trouble if we don’t talk about two key productions, or points of reference. One is The Moors which we’ve sort of had hovering in the air. And the other is your work on The Red Dragon which is more recent and ongoing. So, The Moors, if we could discuss that briefly, and… Listeners to this will be able to buy the text with an excellent introduction and some further interview material. I think it was published by Bloomsbury. But The Moors we could see as a continuation of the possibilities of the kind of two-man model, which as you’ve rightly sketched, comes from Southern African kind of Resistance Theatre, as well as not just theoretically but materially poor-man’s-theatre model. And so, you’ve already talked about how that that has worked in some of your material, but I think that would apply to The Moors as well. But it also turns its gaze on to the contemporary theatre scene, not just in London, but elsewhere, onto questions of casting, I suppose we could say.

Tonderai Munyevu

Yes.

Christopher Thurman

Those who are familiar with Keith Hamilton Cobb’s American Moor might also, you know, find resonances there, although in a different key. And I guess, as you’ve mentioned, that you know, that so often the expectation is that lofty Shakespeare must end in tragedy, but The Moors [laughs], you know, we have the happy conclusion of weddings, as all good comedies must have. A really interesting, fascinating, rich piece of theatre that one can engage with in many ways. But how would you say The Moors marked a shift from the work that you’d done prior to that?

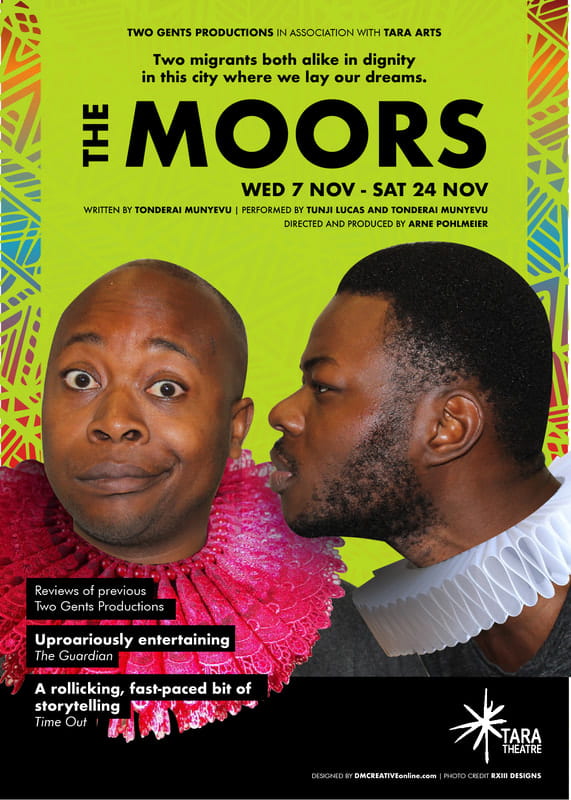

Poster for The Moors (Two Gents Productions, 2018)

Tonderai Munyevu

Well, it marks a shift because I suddenly thought, well, doing a version of a Shakespearean play that already exists, and editing it, and shoehorning myself into it was really powerful and interesting. But at that point, it wasn’t transformative enough for me. And actually, I’d had a very annoying experience with a director at the Globe right after the Globe Festival, because I was, you know, suddenly somebody at the Globe, I think Dominic [Dromgoole] said “Oh, gosh, you’re very good, you’re a very good actor. We should have you here, you know, we should have you here, you’re very, very good.” I was like “Oh, thank you so much, you know, because you know, I am a trained actor, I’m very good, you know.”

Christopher Thurman

[laughs]

Tonderai Munyevu

And so, I sort of do the rounds of auditions [laughs], because I was suddenly very visibly talented, you know. And one of the directors basically just asked me to translate bits of Macbeth on the spot in the audition. Which was very upsetting. It’s a famous name, so I don’t want to use it. But the person, I’m sure, didn’t mean it in that way. But I was very, very upset by it, because it “othered” me. And also, the, her production wasn’t going to be African in any way. So, I didn’t quite see… What it felt like was that there was an enjoyment of my African-ness…

Christopher Thurman

Mm.

Tonderai Munyevu

…and she wanted to experience it firsthand. And I think that’s very, very damaging. And it made me think about the ways in which that African-ness can be so enjoyable in my hands as a way of creating work, and it can be so beautiful for my audiences, who know what’s happening, you know. A lot of our audiences in, for Two Gents, they know what’s happening, they know that we’re selling a play so that, you know, when you do Hamlet, you don’t worry about ticket sales as much as if you do a new piece of writing, do you know what I mean? [laughs]

Christopher Thurman

Yeah.

Tonderai Munyevu

So, there was an exchange with the audience of like, “Oh, we know what you’re doing, you’re giving us something familiar, but you also challenging us with that, and you’re also making fun of us.” And so, it felt to me like a fair exchange. Whereas the situation in a private audition room felt abusive, quite frankly. And it has stayed with me for a very long time, and I just thought, wouldn’t it be great for Two Gents to do something that was Black, actually? So that looked at the Black characters in Shakespeare’s plays, because before then, we hadn’t looked at the Black characters in Shakespeare’s plays. We had made every character Black, you know, by virtue of us two being the people in the plays. Of course, one or two times, we would make someone explicitly white, just for fun, because, you know, you have to make fun of white people.

Christopher Thurman

[laughs]

Tonderai Munyevu

And we felt like, okay, we can do… But Two Gents didn’t feel like a place where we do Black work. Which goes back to that initial discussion we had about labels, you know, because, you know, if you’re Black British, what does that mean? If you’re African… you know, all of that stuff. So, it felt like Two Gents wouldn’t do a play about that. But what I did notice about the three Black characters in Shakespeare—we were just going to look at the Prince of Morocco, and then Aaron and then of course, Othello—is that I could identify them, not necessarily Aaron, but definitely the Prince of Morocco and Othello. I could identify them as migrants, and I loved that about them.

Christopher Thurman

Mm.

The Moors by Tonderai Munyevu (Bloomsbury, 2020)

Tonderai Munyevu

And once I realized that about them, it made me think of Aaron almost as a Black British person. So, it’s almost like there’s me, the migrant who’s potentially Othello, or Prince in Morocco. And then there’s someone who might be a very good friend of mine, who’s Black British, born and bred here—as it turned out to be Tunji Lucas in the production. And it was interesting to look at a Black British person, and what I perceived to be their existence, versus mine, you know. Which is that I know where I come from, I came here for a reason and all sorts of things. So that was really the starting point of that play. And once I knew that the migrant situation was significant for me, I just thought “What’s the most interesting, fun, vibrant way we can talk about these characters?” And, you know, I’ve done other work, which looks at refugees. But this felt like a completely different thing. Again, I wanted it to be romantic, but with a whole other level to it [laughs]…

Christopher Thurman

Mm.

Tonderai Munyevu

… where the romance of what happens in the play within the two couples isn’t really the issue. The issue is the world that we’re in. And yeah, it was also a turning point for me because as I look back on it, I remember feeling that it was very provocative when we did it. And now I’m like, I wish I had gone further. [laughs] I wish I had spoken even more about the real things that were in our vision at that point.

Christopher Thurman

Hm. I mean, this is now, me with the comfort of somebody who’s in the academy who would say something to a theatre maker such as yourself, well, “Can’t you just bring it back again and revise it?” [laughs] Obviously, you know, we know that there are lots of material constraints that prevent one easily doing that. And of course, also creative reasons why you might not want to do that. But before we get to the work you’re doing at the moment, perhaps just something to talk about in terms of The Moors is, again, we talked about audience in terms of geographic variety, or kind of the linguistic demographics. But perhaps you could talk a little bit about age as well, and the question of accessibility, you know. You’ve discussed the boredom or the difficulty of encountering Shakespeare in certain schooling contexts, and you specifically mentioned your own experience of that in the UK. But The Moors is a really, very accessible production of play, not for young people necessarily, but it kind of provides that entertainment, that vividness. Was that in your mind at all, when you were thinking about the work, when you were developing?

Tonderai Munyevu

Well, there was a sensibility of coming to terms with who you are. It was the sensibility of doing something for the first time. It was a sensibility of being misunderstood, almost like first love. That is something that’s always been a part of Two Gents, this idea of adolescence. Because I think one of the things that happens when you are a migrant, is that you are stuck at the point at which you left, you know. [laughs] I left at twelve, Denton left at eighteen, and to some extent, Arne was always a migrant, because he was educated outside of Germany. And so, we’ve talked a lot, I think, in the past about the Prince of Bel Air as a reference point for us. That kind of sense of joy and irreverence. And this idea that actually people are young. So, I think The Moors has that sensibility. I remember when I was playing in the show, I wasn’t thinking of myself as a thirty-something-year-old, at the point that we were doing it. I was just thinking of myself as a young person coming out, as a young person trying to do something. So I think that that was not deliberately aged, as in “This is young people’s work” but we wanted to situate it in a place where there’s an adolescent feeling, a sense of whimsy and romance, that I think young people really, really can easily access.

Now, part of that is to do with also the workshops that we do. You know, we’ve been doing workshops from the very beginning. And we noticed that when we kept things at a certain level, everybody could see into it. And if we didn’t, it would shut off certain people. So, when we were publishing the play, it was really fantastic that it was, “Okay, let’s focus this for young people. But also, let’s write to young people.” It’s like sending a love letter back to yourself, and just saying, “You can do this, and this is how you can do it. And go look out into your own world, see what else is there and make that thing for yourself.” So, I remember that being a particularly proud moment. Because it felt like the culmination of all the workshops we’ve ever done for our work, which we still do, and we’re very proud of. We work with young people all the time.

Christopher Thurman

There’s something quite profound about what you’ve just said about age, and experienced age, or imaginative age as an exile. So, thank you for that. And I’m sure somebody listening to this is about to go and write a PhD thesis on just the few sentences that…

Tonderai Munyevu

[laughs] Yes, thank you…

Christopher Thurman

But let’s talk a little bit more about your ongoing work. You’ve talked about travel, and exile, and your own movements and the travels, and movements of others that you’ve worked with, or audiences that you perform for. But I guess that also requires us to talk a little bit about the movement of Shakespeare, and people love when they are talking about that to invoke the Red Dragon episode, which may or may not have happened depending on where you where you sit. For those who don’t know the story: the idea that a ship, The Red Dragon, performed, possibly Hamlet, possibly Richard II, I think—or was it Richard III?—off the coast of first West and then East Africa on two separate occasions, depending on how you understand the story. I think the consensus seems to be that it’s apocryphal but it’s also a really productive idea, even if it’s not entirely accurate historically, that Shakespeare was performed, at least not in Africa, but off the coast of Africa in 1606, while he was still alive. Tell us what you see you have made of that story in your work on The Red Dragon.

Tonderai Munyevu

Well, I mean, it’s all very fascinating because, that one’s first instinct, one’s first response is, of course, great excitement: “Oh my god, I did not know that, you know, Hamlet was performed on the ship… and oh my god, to Sierra Leone!” And then immediately as an African person, you’re excited. And then of course, you have to go on a journey of, like, “Why am I excited by this?

Christopher Thurman

Yes.

Tonderai Munyevu

“Why is that a good thing?” [laughs] You know? And then, of course, as you say, you start looking into it. And there’s revelations about potentially how this is not what happened. And then that leads to the question of “Well, why does this still exist, and why are we all excited that this potentially did happen, even when we’re faced with the knowledge that it didn’t?” There’s something about us that wants us to believe it. And I think has to do with art as something that we believe transcends geography and all of that. But also, the British have done a good job of saying Shakespeare is culture, and Shakespeare is good. But for me, I was very, very interested in the idea of seeing how impossible this would have been [laughs]…

Christopher Thurman

Hm.

Tonderai Munyevu

… and exploring that on stage. Which means that it’s very, very difficult, because you’re like, “How do I convey the myth here, and what the myth is, and how difficult it would have been for this thing to exist?” But more than that, “How do I bring it into the here and now? In today, really?” And for me, it’s about looking at something that we’ve done as Two Gents, which I think other companies did do as well, which is that Black British people, not that we were British, but Black British people go to Africa, they go to India, they go to China, and wherever, and they perform Englishness, but now they’re Black British people, with British accents, doing that. And I find that so fascinating. Because it’s a neocolonialism…

Christopher Thurman

Mm.

Tonderai Munyevu

… if you like. It’s the same sort of thing that’s being communicated. But what if Black British people then think about their own history, which is linked to the sea, which is linked to travel, which is also linked to forced travel? What happens, then, you know? Let’s say that a company is brought to Sierra Leone in 2027, or whenever, and then they’re asked to do the sort of celebration of the Red Dragon having gone there. And they have their own realization of who they are, and what they’re actually doing. And I just thought that was interesting to explore it that way. And at that point, also speculating about how genetics will become far more important for people. You know, every one of my friends who’s Black British is having this test that tell you where you’re from, you know, 43% Nigerian, 23% [laughs], you know? In fact, somebody was saying to me the other day, they are 53% Sierra Leonean, which I found fascinating because one of my characters is a Black British person who has discovered they have a percentage of Sierra Leonean in them, and they arrive in Sierra Leone…

Christopher Thurman

Mm.

Tonderai Munyevu

… to celebrate this thing, which is violent somehow, really. And they have a moment of self-realization. And so, it’s really about that, really. That’s what I’m looking at. And so, a lot of questions, you know?

Christopher Thurman

It’s absolutely fascinating. I am impatient to have the opportunity to watch this work and to read it and to engage with it. Is there a sense in which you see a point of inflection between these investigations into one’s historical DNA identity… There’s the question of, you know, kind of national or regional identities or transnational identities. Would you say that there’s a kind of echo or resonance between that slippage or, let’s call it fluidity, and then questions of gender fluidity? So, we could talk about the kind of non-binary celebration of, or kind of non-binary existence in The Moors for example, and you’ve talked about, you know, how that influenced some of your work, whether we’re talking about gender or sexuality in Kupenga Kwa Hamlet or…

Tonderai Munyevu

Yeah.

Christopher Thurman

… in Vakomana Vaviri Ve Zimbabwe. Does that continue into The Red Dragon? Or, or, is, am I…

Tonderai Munyevu

It does. No, no, it absolutely does because I’m interested. I mean, there’s a lot of research I’ve been doing on it. And I’m interested in homosexuality on ships, and how if there was a performance, who would have played Gertrude and Ophelia, and what that would have looked like, but also of power and masculinity within that world. But also just then looking back at time, because we do have a character in it, who’s lived since the seventeenth century, he’s a Black man who’s lived by the shore. And, you know, how queer people in Shona culture, certainly—I’m going to do a lot more research about Sierra Leone—but the idea that the non-binary queer space is actually the spiritual space. And that’s connected to the water. And so yes, there’s an element about what the water contains, and who survives, and who’s in the third space, as we like to say, or that space that’s spiritual and human at the same time. And trying to thread that through the play has been quite a challenge. But I think the work demands it.

And it again, it has to meet this moment. The biggest thing for me with the Red Dragon myth is, is the idea that actually we should start redacting Shakespeare. We should start taking things out that are problematic. And I can’t believe I’m saying that. So it’s like, you know, Othello, this whole journey about the beast, and, you know, let’s just take it out, because Shakespeare was under the impression that this was potentially something interesting to people. But let’s just take it out, because it hurts our feelings as Black people today. But again, working through all these ideas of inherited culture, and what that means, also is to say, “Don’t make me a man or woman, I am a person.” I mean, you know, all of that. I think it’s about bringing it into the now in front of an audience, but also challenging that audience, you know, just saying, “What do you want from us?” And I think The Moors was really powerful at just saying, “You are complicit in this thing of me acting and you watching me, you are a part of it, and I need you to think differently,” [laughs] you know. “I need you to demand that this ritual of performance is changed.”

Title page of the typescript-in-progress for Red Dragon: A Protest Play by Tonderai Munyevu

Christopher Thurman

And if we briefly put our kind of theoretical lenses on, or put a theoretical framework to that, there’s the question of, to be good Judith Butler scholars—you know, of gender as performance. And to say, “Well, you know, there’s a complicity in your expectation of what I’m performing for you, but that also applies to the gender you expect me to be, or the kind of identity that you expect me to inhabit.”

Tonderai Munyevu

Yes, because then race, race becomes a part of that, you know? Sometimes one feels like race is a performance too, you know? [laughs] You start going, “Oh, I’m a Black man.” “Oh, I’m a Black gay man.” As a way of figuring out codes of behavior. You know, what are you without that? Then your performance of yourself is different. I mean, we’re all performing, right, to some extent? But linking that, one of the things that we want to do with Red Dragon is really to link in with the dilemma that Hamlet himself has, right? So, Hamlet is going, “I cannot do anything about this situation.” And he’s talking about that situation. And then the situation is forced upon him, right? The tragedy of the end. And it’s the same, I think, for Black people, or queer people. I am both that person making this work going, “Oh, I feel despondent about how much I can do. This is too big a challenge for me to take on. How do I take this on? I’m better off just getting on with it.” You know what I mean? This is bringing that full circle.

Christopher Thurman

Yeah, absolutely. And I’m not going to try and pursue an analogy or comparison to what happens in the plot of Hamlet. But I suppose what we could say, as people who’ve benefited from your work is to encourage you to continue [laughs] to carry that burden, to fight that fight or to dwell in that place of difficulty, because as is always the case with audiences, we thrive on the work that you do as an artist, which is hard and difficult, but also joyful. And that creativity is something that we can celebrate. And I’m so, so glad Tonderai, that we’ve been able to do that in this conversation. It feels like we could talk for hours and hours getting into more detail, but I think this has been a wonderful primer, I almost want to say, for listeners to get a sense of your work, your career, your life. But also, you’ve just opened up so many different ways of thinking about theatre practice from the perspective of the theatre maker as well as the audience member. Thinking about our location, geographical, national. Thinking about our identities in terms of race and gender. It’s been positively thrilling for me, and I can’t tell you what a great privilege it’s been to speak to you. So, thank you so much for everything that you’ve offered today.

Tonderai Munyevu

Thank you for having me. I, like you, we could talk forever, really.

Conclusion

Amrita Dhar

If you enjoyed this conversation, please subscribe to this podcast, spread the word, and leave a review. Do take a look also at our project website at shakespearepostcolonies.osu.edu for materials supplementing this conversation and for further project details. Thank you for listening, and until next time, for the Shakespeare in the “Post”Colonies Project, I am Amrita Dhar.