Postcolonial Shakespearean Authorship and Activism in India and the UK

Keywords: India, Great Britain, Imperialism, Education, Social Movements, We That Are Young, King Lear, Language, Kashmir, Intertextuality, Poetry.

Interview audio

Published on 3 October 2023.

Preti Taneja; photograph courtesy of Ben Gold

Interview transcript:

Introduction

Amrita Dhar

Hello and welcome. My name is Amrita Dhar, and I am the Director of the project Shakespeare in the “Post”Colonies which is hosting a series of interviews with postcolonial Shakespeareans from around the world.

In today’s conversation, my collaborator Dr Amrita Sen and I interview the South-Asian-inheritance, British-based educator, screen-writer, and novelist Preti Taneja.

Conversation

Amrita Dhar

Preti, could you start us off today by telling us a little bit about yourself, about your postcolonial inheritance, but that you’re in the UK? How has it been? Just a little bit about yourself, please.

Preti Taneja

So, I’m Preti Taneja, I am a Professor of World Literature and Creative Writing at Newcastle University, and I am a writer and activist and the author of two books. One of them is called We That Are Young, and it’s a transposition or translation, as I call it, of Shakespeare’s King Lear set in contemporary India. The second book is called Aftermath, and it is a kind of hybrid memoir, based on my experience teaching in prison, and terrorism. A little bit about myself in terms of the question that you asked, I was born and brought up in the UK, and I still work here. I don’t consider it could be a post-colonial relationship, obviously, because I don’t really think there is such thing as the “post-colonial.” I think it’s just a thing that changes shape. Living, working, being British, I have a different perspective on that, perhaps than people who, are in the diaspora in different parts of the world.

Amrita Dhar

Can you talk a little bit more about that? I think I find myself agreeing that this is just something that has changed shape in large parts of the world, changed vocabulary, but hasn’t really changed. Could you talk a little bit about what you mean by “there is no such thing as post-colonial” in your assessment?

Preti Taneja

Well, if you know the way that structures of power reiterate and repeat themselves, and a little bit about the British system, what happened after 1947 in India, in the Indian subcontinent, basically translated after the British left India, to recreating Empire back in Britain, essentially through immigration structures. So, we have a working-class Muslim, Pakistani, Bangladeshi community. And we have a middle class. That includes mostly Hindus, they mostly work in the professions rather than arts and culture. There’s a strict kind of curatorial system, is in place here that has been 75 years in the making, and it rests on one extremely important thing: the fact that we do not teach Empire at school in this country, where I am in the UK. So, the real harms and damage of colonialism do not exist in the public consciousness, generation after generation in this country, that continues to allow for violence to be perpetrated, for ideologies to take root here. Because into that void, which does not allow communities the dignity of origin stories, a number of ideologies are able to take root.

So, what you’re looking at basically is a reiteration, 75 years on, of divide-and-rule culture, which is extremely difficult to reverse at this stage. But luckily for us, we do have also a counterculture of solidarity, of resistance against whiteness and imperials, you know, human rights abuses, employment laws, segregationist practices, and so on. Solidarities that cross Hinduism, and solidarities that cross gender, and solidarities that cross Black and Brown. Those unique things have arisen out of a particularly British context. The stronger they are, the more pushback there is from the state. Tokenism is alive and well in this country. Some of us are beneficiaries of that system, and we carry the burdens of it, too. It’s a very interesting position to think and write from and to teach in.

Amrita Dhar

Yes. There is so much resonance. I grew up in Calcutta. So, I was always told that, you know, we are literally “post-colonial,” that my reality is of political independence. I was born in independent India. And the older I get, the more I realize that first of all, I did not grow up in genuinely post-colonial India. Perhaps I’m realizing that there is no such thing as actual “post-” that is after colonial political reality. It’s just changed. It’s a kind of neocolonial reality that India is in right now. And it’s unfortunately very similar in this country too, where there is a great a great deal of pushback against grappling with what this country stands on, the US, that it stands on genocide, on chattel slavery, on continuing war. We don’t like to talk about these things. And if we say, I mean, even something like just basic Critical Race Theory, it’s under legal attack in this country in multiple states. So, it’s not edifying, really, how similar… [laughs]

Preti Taneja

The impact of trans-Atlantic slavery on the Americas obviously has a huge and different relationship to racism, creates a different atmosphere…

Amrita Dhar

Exactly.

Preti Taneja

… the fact that, that guns are legal…

Amrita Dhar

Exactly.

Preti Taneja

… the fact that your healthcare is not state-provided. These important things make the situation in America more visible and more debated, and well, in America, slavery was visible and present in the country. In the UK, the violence of slavery was hidden from public view. Because it took place in the Caribbean, in Jamaica. It took place in Empire, in the colonies. The proceeds enriched British families at home. So, people in England got very, very wealthy on the back of something that no one else could really see the horror of in the same way as, obviously, that is visible in America itself. So that allows a culture of silence and denial that does insidious harm.

There is an ongoing problem with racism and the police. There’s an ongoing problem with the rise of right-wing fascism in this country. There’s a kind of colonialised mindset in institutions, which keeps people in place. It really is very difficult to get ahead—or to put your finger on what racism is actually doing and how it’s operating through more insidious ways.

Amrita Dhar

The biggest reason you’re in this series is this fantastic novel We That Are Young, which is, I would say as a Shakespeare Studies person, a brilliant transcreation of one of Shakespeare’s major plays, King Lear. I had two questions to get us into this book. One is what was Shakespeare like for you, as you were growing up, in your education, as you were coming of age? And second, what got you to write your first novel, your first major work, as an afterlife of Shakespeare, and especially King Lear?

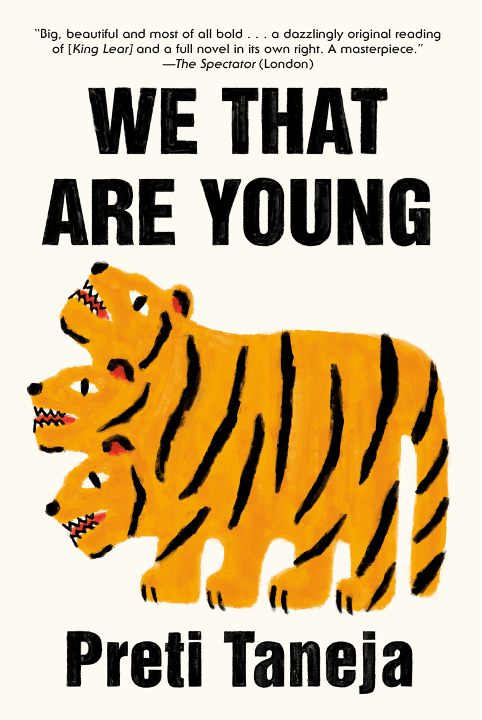

We That Are Young by Preti Taneja (Penguin Random House, 2019)

Preti Taneja

Well, to take the first question—what was Shakespeare to me. Shakespeare is the centre of the education system and literature in this country. From an early age I was reading Charles and Mary Lamb, watching animated versions of Shakespeare on television. There were filmed or televised BBC adaptations with great British actors. It’s in the ether all the time. And one cannot help but to be in thrall to the poetry and to the mystery as a child. You’re open. And that sense of wonder and awe at what language can do and what mysterious things can happen—and the plots of Shakespeare are so full of doubles and pretense and play acting. And they delight children.

I encountered Lear when I was probably sixteen, for the first time, and it was on the national curriculum as the literature text for our exams, GCSEs. Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet were the GCSE texts for the school I was at, and then King Lear was the A level text. And like I said, there was no teaching about Partition or Empire in British education system. But I was very aware of that history because obviously I had heard the stories from my mother and grandmother, from my aunts, and other relatives growing up. The reason I was born in England was that history. My grandmother was a Partition refugee. She was a young bride. She was pregnant with my mother, who was born in December in 1947, in Delhi. So, it’s a very alive history for me, but it was never endorsed at school, because there was no one talking about it. There was no books about it. It was almost like they were making it up. And then I studied Lear and everything clicked into place for me, because there at the centre of the English literature classroom—and I was an avid reader and literature was my subject—was the Partition story, was the story of obedient daughters and being made to perform. Which is very comfortable territory for, unfortunately, for South Asian women [laughs], in diaspora families, as well as India. Was the story of servants I had seen… Even in the most modest middle-class homes of family members in Delhi, there were people doing jobs which we did ourselves at home in England, who were employed by the household to do those jobs.

So, I was aware that there was a kind of feudal structure in the country of my parents’ birth that they had left. And all of these things kind of fused to me. And then there was, of course, the poetry, and the doubleness of the language, and all of these ways in which truth speaks to power in that play. And it became something that was like a talisman for me. And it wasn’t ’till I was in my early thirties that I decided to try to work through some of that, which has stayed with me all of my educational life and my work in human rights, to try to write this novel, which turned out to be We That Are Young.

Amrita Dhar

It’s so interesting. I mean, in my family… Both my parents were refugees of the Partition. When I grew up, 1947 was not thought of—I’m a Bengali—1947 was not thought of as the date of Independence. At home it was always referred to as the date of Partition, the date where when my parents, both their families, had to leave their homes and try to make a home in this new country that had just been sort of born as a nation in 1947. But it was not Independence, it was Partition. That was always the word that they used.

Preti Taneja

Yes. The trauma lasts longer than that sense of a new nation state’s borders being defined.

Amrita Dhar

And we’re having this conversation as, in the Indian subcontinent, the two countries that were then created, India and Pakistan—it’s been seventy-five years since then. And the scope of this interview is not such that we can unpack what it means to be seventy-five years onwards from 1947. There is a lot to talk about there.

So, in the novel, something that so resonated with me, was how—and this is something very Shakespearean about you—how wonderfully you can depict what power actually looks like. That is, we know Devraj is this magnate, he is the hub of power, he is the person of the Company. But, this is something that you were just talking about, you know, that you have servants who do certain things for you, even though you’re in a position to do those things yourself. You talk about this in more detailed, in more granular fashion, in the book, where you’re talking about, for instance, in Delhi, what the garden looks like. Someone who knows Delhi immediately knows, this is that arid bowl in the North of India, where any kind of ecologically responsible person is not going to have a green, green garden. Can you talk a little more about how you created the world of We That Are Young? How you made power visible, and then how you made the fissures in that world visible?

Preti Taneja

I’ve been visiting Delhi for long periods of time through my childhood and adulthood. It’s a very familiar city to me, a beloved city. And nooks and crannies of it, I feel a very personal and deep connection to as well as certain areas of the city which I’ve seen change and become more gentrified with the kind of changing fiscal nature, of the country over time. To create the Delhi of We That Are Young meant taking all of those memories, but also being very true to the idea of myth and fairy tale which the book is permeated with and setting in that epic space where anything feels possible. Because in India, I feel like, and in Delhi in particular, anything is possible if you have enough money. There’s references that readers might catch or might not to The Wizard of Oz, the yellow brick road, the yellow brick wall, and the lions and tigers and bears on the gate of the farmhouse. You’re supposed to feel like you’ve landed in the space of possibility, but also that has a kind of brutal edge to it.

I think geography, environment, and place and the way in which money can manipulate that do have a lot to tell us about how power operates. Once you have that kind of money, what is there left to do except order the world to your will, right? So, then you start thinking about, as a fiction writer, what might that feel like and that might that look like to read about? What do you want your reader to have as an experience? If you mean to create a situation where monsters prey on themselves, you have to stand in the shoes of each character in turn, and believe with them that they’re right, while you’re writing them, and then turn that kaleidoscope so the next character feels equally compelling and equally true and equally believable. And your allegiance as a reader switches, but you still remember that you were possessed by the previous character.

I do that in the book through structures. The book’s told in six voices, five young people, the three daughters and the two sons that appear in Shakespeare’s King Lear, and Lear himself. And I fill in some gaps that Shakespeare leaves us to, for our imaginations, voicing a time period, which is a lost time period in Act V of the play, where Lear and Cordelia just disappear from the action until Edgar goes, “Oh, great thing of us forgot!” and suddenly they come back. So, in the novel, you get to know where they were and what was happening during that gap. And it’s by kind of situating myself with each character in turn that I was able to create that prismatic sense of what power looks like, and what those power hierarchies are. So obviously, the patriarchy comes sharper into focus, in that sense. It’s a polyphonic narrative, and it comes from a carnivalesque literary philosophy, Bakhtinian philosophy, for people who read that kind of, that bent of criticism. As a novelist, I love what plays can do, the space in theatre, what the political theatre can do, and for our consciousness, as well as for our entertainment. My hope was to bring some of that hard-edged-ness to the novel.

Amrita Dhar

Which you very much have. You mentioned the word “epic.” There is an epic quality to this play of Shakespeare’s. Your chosen form, the novel, does enormous justice to that epic quality: in size, in shape, in how many poetic voices you allow yourself. The writing is ultimately sometimes hard-edged, yes, often hard-edged, but it is poetic. Which is something probably that you just do. But can you talk a little bit about this awareness of genre and you working through the qualities of the novel form, the epic form, and the theatrical form?

Preti Taneja

Yeah. There’s a writer whose work I really love, David Shields. And his book is called Reality Hunger. And in it he writes, quoting from someone else, that genre is a “medium-security prison.” And I believe that. Genre makes no sense to me. I don’t think it made sense to Shakespeare. Because the register, especially in Lear, goes from high to low in the same speech from the same character’s voice. And it’s very honest about the fact that we are what we read. And we read many things, from adverts to Twitter, to newspapers, to literary journals, to academic writing. We take in information through our eyes all the time, and it creates our voice in our minds. As well as the mother tongues, and I mean that in the plural, that we have as postcolonial subjects, or subjects of an empire, or growing up and being born in countries that our parents did not grow up or were born in.

For me, like, playing like that is really exciting. I owe a lot to poetry. I loved learning through close reading of Lear, just how subversive language can be. The English language, which was the language of being civilized, it was the language of being outside my family home. It’s the language of schooling and administration. Yet here I was, looking at this play at sixteen, seventeen, and learning that “bond” can mean money as well as love.

And patriarchy is there, just there, in that one word as you twist it. It feels very stark, it feels very obvious to talk about these kinds of puns now, but back then, it was what I found thrilling. That you could do that with language and pass into the canon. That power could be critiqued through language, and could still embrace that critique, because the language was just so compelling and beautiful. And so, it’s a lesson in how to break down what we’re constructed of and remake it to our own will. That’s, I suppose, what writers do, that’s what we are for. In doing that, we question language, question power. We question the limitations of our own imagination to pushing the boundaries of something all the time and saying “The form has no border. The sentence has no border.” [laughs] The possibility—because even if you think it ends at a full stop—as to the depth you can achieve. And it’s the deep dive through, through two or three words that you can make, and thrill the reader. Just as you were thrilled when you first encounter it in someone else’s writing.

Amrita Dhar

Right. And how infused We That Are Young also is… It relates to what you were talking about earlier: the specific realities of each person that is speaking. Which also is in obvious ways dramatic. It is in obvious ways, theatrical. It is in obvious ways Shakespearean. The play itself, of course has… It’s a play, but it has poetry. It has some of the finest poetry, I would say, in the English language. That, too, is clearly part of what you have taken from this work, King Lear.

Preti Taneja

The book itself was something I set out to keep as closely as possible to Lear in its characterization. My reading of those characters, the language, and the structure of the play. The scenes fell quite nicely into each character’s section of the book. And to cover everything I could about it. So, it’s got eco-criticism, it’s got gender criticism, it’s got religious and fundamentalist criticism. For me to know that from readers and other scholars, that I was even a little bit successful, that is really wonderful. But at the same time, I really want to draw attention to the other intertextualities in the book. Because it’s not just about Lear [laughs]. It’s about weaving together something for politics, for political fiction. In this book, you’re going to find Faiz Ahmed Faiz. You’re going to find Rumi. You’ll find Sanskrit aphorisms. You’ll find protest songs. All sorts of different languages, some that I made up. There’s places that don’t exist in India that do exist in the book, but the rest of the places are real. There’s a whole way of constructing a politics in fiction and using all those tools to make something that feels true to something, a source that also has to stand on its own, and feel contemporary, and have arisen. Just like second generation diasporic young people grow…

Amrita Dhar

Yes.

Preti Taneja

… into many languages, into many worlds, carrying all this poetry that we mix inside our own brains. And this is how it came out. It didn’t just happen, obviously, it took a long time to craft each sentence of that book, but its origins are a deliberation in hybridity.

Amrita Dhar

And I have to say that is true of Shakespeare’s moment of writing this play. Where he is inheriting what he is inheriting about the Lear story. The way he reworks it is about him existing as a writer in his moment.

Preti Taneja

That’s right. It’s about that feeling of you have something that’s happening, you have something to say. The world is changing, the lines on the map are changing around you. There’s a new king in town. There are different rules on blasphemy. There are things you can say, there are things you can’t say, and you have to find a way all the way around that in order to make art.

Amrita Dhar

I find it just absolutely stunning that what happens between the 1608 Quarto version, and the 1623 Folio version of the same play. And they kind of become different plays because of how Edgar looks.

Preti Taneja

Right, lucky me, I really liked the fact that Edgar has the last word in the Folio edition, and that’s why he has the last word in the novel, obviously. Because it gives the whole book its shape and its title and makes a lot of sense that it’s that character, the new fascist, the new [laughs] dictator rises when the old doth fall. That’s what we’re basically saying, to borrow from Edmund. But, you know, if I was to write We That Are Young now, things have changed a lot. In my own thinking about what those characters might be and do. For example, Radha, who is one of my favorite characters, is the Regan character from Lear, and the Radha in We That Are Young has very little power on the surface, but she has her own power in the technological world. She’s running a Twitter account under an anonymous handle, and she’s kind of manipulating the share price of the company, which of course, has ripple effects for millions of people. But I was writing before #MeToo. I think she would have had a different storyline, almost, if that had been happening around the same time of writing. So, it’s always interesting to see how you work dates and what you might do differently if you were doing it now. And yet, you have to stay true to the moment you were in.

Amrita Dhar

As a literary critic talking about this book, I am thrilled by the level of craft, and the level of faithfulness of this work to Shakespeare’s play. At the same time, part of me wonders, well, what would have happened if it weren’t as faithful? What would have sloughed off? What would have come in, and what kind of challenge was it? Or did it feel like a constraint to have Lear as the thing that came before this?

Preti Taneja

The only real constraint with writing with big, big canonical texts, with Lear, for example, is because the language is so compelling and so famous, and it’s so much inside the psyche, that when you’re writing those big set pieces, like a storm scene, or the love test, somehow Shakespeare’s language creeps in [laughs] and takes over. So there’s a constant thing about doing a little tussle with your own confidence or your imagination to say “How can I keep this in the world I’m constructing and let it stand on its own two feet with those flickering through of Shakespeare that people delight in if they know the play, and they won’t miss if they don’t, when they read the book?”

Amrita Sen

A lot of the reviews and a lot of commentators talk about how you place your novel, We That Are Young, in contemporary India. I want to specifically ask you why you wanted to set it within a corporate setting? Why not anything else? I ask this because compare it with, say, for instance, Vishal Bhardwaj’s cinematic adaptations. He sets them in the murky Mumbai underworld. So, his sort of preferred modus operandi almost, is the criminal underworld. And so, I was sort of curious to know why you chose to set your adaptation of King Lear in corporate India.

Preti Taneja

I wanted to stay as true to the spirit of the play as possible. I guess I’m interested structurally in the criminal overworld…

Amrita Sen

Ah…

Preti Taneja

… rather than the criminal underworld. For me, it’s really corporate power that is the kind of architecture of our society these days. Global capitalism, when it’s bolted into nation building, bolted into religious fundamentalism. That is really what I’m interested in. I’m interested in the heart of power, in the widest and broadest possible sense. I’m such a fan of the Bhardwaj adaptations and his work. What they do is shine light on those particular localities. But even those localities are inside a bigger structure, which is capitalism. A bigger kind of way of thinking about how all of us are implicated is what I’m interested in, in both my books, in We That Are Young and in the second book, Aftermath. So for me, you know, to think about the relationship between India and its roots in Empire, for example, contemporary India’s roots in Empire, which started off as a colonization through trade, through the East India Company, which is obviously going to lend itself to the idea of the Devraj Company, and the ways in which the traces of Empire have stayed and consolidated into what contemporary India is legally, and fiscally, and ideologically. It’s not British, but it’s a kind of different iteration of fascism, in my view. And I think looking at money is always the way to understand that most clearly.

Amrita Sen

It’s so fascinating that you mentioned the East India company, because you do refer to Devraj’s company as “The Company,” and it kept reminding me of the East India Company. I wasn’t sure if that was just me…

Preti Taneja

Yeah, there’s nothing in that book that isn’t intentional. It’s interesting because when you’re writing, you wonder: is this too obvious? Is this too on the nose, as they say, calling it the Company? But it isn’t, and I’m a big fan of linguistic duplicity and plurality, of puns, essentially. So, when I think about the Company, I think about theatre companies, which is obviously a lovely way of referencing the play as its original form, and it’s also East India Company, and the kind of global corporation that we’re talking about. So yes, it was completely intentional. I’m British, you know, I was born in England. For me, growing up at the centre of that empire, at the centre of that power, was the lens through which I wanted to critique what I see through the play.

Amrita Sen

Hm. Right, are there…?

Preti Taneja

When we think about it, you know, it really is because of the East India Company that Shakespeare came to India in the first place. So, it’s important that we acknowledge those chains of cultural dissemination and check chains, obviously, in that sense of being enslaved to something.

Amrita Sen

No, absolutely. In Calcutta, we were, you know, of the first areas that sort of came under direct Company rule, and the city itself, at least in part, traces its origins to the Company. There might have been three villages that were already there, but it didn’t come together as, as a global capital, before the Company. And the reason why we study Shakespeare here in Calcutta is again, very much because of the Company and specifically the elite class that it helped generate, right? Which would be Indian in skin, but English in all other sense. And I think it is equally important for us to acknowledge where we come from right? From, from that extremely privileged background, which is why, honestly, I think I’m sitting here talking about Shakespeare because I belong to the newly-generated middle class that came to be because of the Company in the nineteenth century. And its aftermath. The other thing that struck me about We That Are Young is something that goes back to Shakespeare’s original playtext, I think, which is the absent mothers. And I was wondering if you could say a bit about the absent mothers and how they seem to haunt the novel, right? I mean, Jivan’s mother, of course, but also the mother of the three girls. Also Devraj’s…

Preti Taneja

This question’s always been a really interesting one, because obviously, our mothers play such a large part in culture, cultural control and cultural conditioning in South Asian families. And often as instruments of patriarchy as well. So, when you remove that presence, you have a sort of anarchy, the possibility of anarchy, and the possibility of true connection. Taking it from the children’s point of view—anyone who was close to a mother that they’ve lost will understand this—but they never die. Not only do they never die, but they become what we wish they were at any moment that we want them to be that. Of course, in reality, they may not have been the way we wish they were or can imagine them once they’re gone. But they’re not around to remind us that they’re also human with complex foibles of their own, they would also have got annoyed with us, or told us off, or whatever.

But grief is a central kind of construction of the book, and the fact is that mothers do not exist in Lear in any embodied presence. So that gives the novelist an opportunity to think through, because obviously, with transmuting, or translating a play structure into a novel, there are certain things that formally you have to do that you can get away with not doing in plays. So, where the play space allows you for some more kind of existential spaces that open up, and silences… and our suspension of disbelief works in different ways, you can cross the stage from London to Dover in two steps. Or you can imagine that she’s just not there. When you’re writing a novel, those are the gaps that one has to fill, because narrative demands that, almost, or some kinds of forms of narrative. Of course, there are forms you can write in that you could probably replicate some of those more existential things. But my novel is sort of epic and hyper-real and it’s got that blaze of social realism to it as well. So, I had to answer those questions formally as an artist. What was Jivan’s relationship to his mother? How did they end up in America? What was her relationship to Devraj, and to her husband? With the girls—because the Kashmir storyline in We That Are Young is the heart of the book, really. And everything in the book drives its way to Kashmir just as in the play, all the action drives its way to Dover. How to connect this family, who are not Kashmiri, to that land, could only be through this missing mother. The annexation of the land could only happen through that marriage. For this particular family, which is a synecdoche for Hindu state violence in Kashmir.

A felled tree with the words “AZAD KASHMIR” etched on its trunk; photograph courtesy of Ben Crowe

Amrita Sen

I would actually like to hear more, especially with how you bring Kashmir in and how your novel effectively becomes a postcolonial critique, not just of Shakespeare, but also of the post-colonial state, in effect. So, if you could possibly say a bit more about that…

Preti Taneja

So, my background is in human rights advocacy and reporting. So, before I became a writer, and now an academic or teacher and university professor, I worked for a long time in minority rights advocacy. I travelled extensively.

A Kashmiri cook in front of a wood-and-coal fire, in the process of making Wazwan kebabs; photograph courtesy of Ben Crowe

A Kashmiri cook at work in front of a wood-and-coal fire, in the process of making Wazwan kebabs; photograph courtesy of Ben Crowe

The hands, needle, and threadwork of a pashmina embroiderer; photograph courtesy of Ben Crowe

Preti Taneja sitting across a pashmina embroiderer and admiring the embroiderer’s work; photograph courtesy of Ben Crowe

And I’m very interested in the traces of the law, and how the law replicates itself across time. So, when you look at the Indian constitution, or the Indian Penal Code, you see these laws and practices that were enshrined by the British into the Indian system. So they’re bolted into the psyche of what the nation state is and how it imagines itself. And they’re very useful things for people to keep using. You’ve got Victorian-era laws on gay rights shutting down the right to your freedom of sexuality. You’ve got colonial-era laws on the powers of the Army to act with impunity. And this is something that Vishal Bhardwaj draws on very much in Haider as well, which is obviously set in Kashmir. And they just lasted into a period where the state’s violence, the new nation state’s violence was taken to work. So, when we step into those boots, what are we becoming? That’s the question that Lear is asking of us. When we think about becoming our elders, or our predecessors in the legal sense, of taking on those colonial-era violences that allowed the British army to act with impunity towards Indians. [laughs] Now Indians are using them against Muslims, or people from different parts of the country, different kinds of minorities. What has the state itself become? What do you mean when you say “post-colonial,” because I don’t see any “post-” in this whatsoever. And as a person who is in the diaspora, and lives again, like I said, in the sort of heart of Empire, what I see in Britain is that this thing never ended.

An old houseboat on Dal Lake; photograph courtesy of Ben Crowe

You know, they may, the British may have quit India in 1947, but they just came home and recreated it here, with the same structures of power, with the same kind of “Hindus can rise in certain classes, and Muslims may not,” so we still have that here. And what we’re seeing in Britain at the moment, is that void in our education system, because we don’t teach Empire history here, is now being filled by the same Hindutva violence of ideology that’s happening in India. So, we’ve had, you know, communal riots in Asian areas of Britain over the weekends, the last few weekends. It’s crazy. It’s like watching Partition re-unfold in real time and here at home. So, the book’s, just to come back to the novel—Obviously, I wouldn’t have written about that, because the book came out five years ago, and I was writing five years before that. Any good novelist with a journalistic background especially, you’re used to looking at minority rights abrogations as a barometer for fascism and fascism’s rise. You can literally trace the playbook if you know what you’re looking for. That’s what I was doing when I was thinking about the presence of Kashmir and how to make the story, weave that story into the novel. And luckily, Shakespeare understood the viciousness that borders and boundaries do to our minds and to our lands and to women’s bodies. [laughs] It just translates, maps almost scene for scene onto that play.

Amrita Sen

What’s really intriguing is that both mothers, I mean Devraj’s wife as well as Jivan’s mother, they seem to come from the margins, I mean, if not geographical margins, then certainly societal margins. If Devraj’s wife is Kashmiri, and then, which occupies its own type of politics. Then Jivan’s mother comes from Punjab, from an old family of performers. I kept thinking about how, during colonial rule, the profession of the dancer or the profession of tawaif [courtesan], was actually criminalized. Whereas before this, that was not the case at all. That also seems to occupy its own type of further marginalization and persecution that empire seems to bring. So, the two women were doing really interesting things in terms of pointing out the really fraught colonial legacies about specifically how we deal with the body of the nation, in effect. So, more like a comment than a question, but I really thought that, that’s a really interesting and intriguing.

Preti Taneja

Devraj’s wife is a Kashmiri Pandit, she comes from a Pandit family. The reason why he marries her is because of Land Laws that give him access, as a non-Kashmiri, to Kashmir. So, when you say the margins, I mean, margins are relative to where you believe your centre is. And obviously, Pandit history is Nehru’s history. So, one of the main reasons why he wouldn’t give up Kashmir is the promise of plebiscite that’s never, still not happened. And all of this trauma was solidified in Partition, was because of that Pandit ancestry. So, in many ways, she was an elite, the daughter of an elite. This is a very, very heightened issue, this question of Kashmiri Pandits versus the seven decades of sanctions that Muslims have faced in the valley.

And the book… My personal view is that violence should not beget violence. Some of my dearest friends are Kashmiri Pandits, people who I love, in my family, who brought me up. And yet I’ve worked in minority rights all my life, and I just think at some point, we have to kind of stop. Otherwise, where are we going with this? And opening a multiplex and flooding the place with tourism of a certain ilk—it might be a panacea and change minds, but those things are still there under the surface. I mean, so many people have died. So many women have lost their husbands, so many sons have been disappeared. It’s, it’s extraordinary how many years of education have been lost. And so, the book really tries to think through the legacies of that empire-level violence. And then capitalism bolted on to this settler-colonialism, which is now creeping, creeping, creeping even further. Which I could see coming, on the ground, when I was there when I was researching the book in 2012. It came to fruition, with the sweeping away of those protections, of constitutional protections. Three years after the book was published. But it’s there in the book, that prediction…

Amrita Sen

Yeah…

Preti Taneja

… I think there’s a paragraph… I can’t even remember what it says now because I wrote it, you know, a while ago, but there’s a moment where Kritik, who’s the Kent character, tells Sita, the Cordelia character, that the Constitution doesn’t mean anything, and if he wants to, he’ll just pay some money and sweep away that law that means that Kashmir has a semi-autonomous state. And I wrote that in August of 2016? ’17?

Amrita Sen:

Yeah, yeah. But something else that I also wanted to talk about, which are the other voices, literary and otherwise that enter the novel. Shakespeare of course, but you start off with Kabir. And there are, are references to the Slumdog Millionaire, and also to Bollywood movies. I wanted to think about and talk about what the plurality of other literary and cinematic and creative texts are doing in the novel. And, perhaps how they might be working towards opening up another type of space?

Preti Taneja

Intertextuality is a political choice for me, it’s a craft. It’s a resistance choice. It creates an identity which won’t be pinned down. Because it de-borders us, it decolonialises us [laughs], and it allows us as hybrid people who come out of all of these different traditions, especially as women, as South Asian, Brown women with diaspora upbringings and colonial-era influences—you speak English, you speak Bengali, you speak some Hindi, you understand the poetic traditions of all of those three places, you grow up with American culture dominating mainstream global culture—so how can we deny that when we’re writing about the societies in the world that shape us?

So for me, to weave all of those things in together creates this refusal to think of nation-state borders as fixed boundaries for my imagination, and for my identity in my body. And I think that’s true with many, many millions of people who live within the word that is India, the word that is England. For me, you know, multiplicity in language and intertextuality is a way of me making new worlds and expressing the world as I feel it really is. Obviously, if the setting was different, if the characters were different, if the novel demanded it, that would be different. But this novel, demands that this will be accurately represented in all of its hybridity as a positive thing, not as a “I’m so ashamed that I’m miscegenated in some way.” I’m not. Because we all are. [laughs] There’s no such thing as authenticity, there’s no such thing as purity.

Amrita Sen

Thankfully. The absolute horror of the “pure” and the “authentic,” right? It, it’s much more fun, and interesting, and life-giving, I think, to…

Preti Taneja

So much more life-giving. And I think, you know, that this novel and a lot of my work, this book, the next book, the stories, they upset people who want that. I have questions in England, “How dare you write about Shakespeare, with Shakespeare?” I heard questions in India, “Why don’t you write about your own country?” I have people in reviews concerned, outraged, that this book exists, because it’s doing something that shouldn’t be allowed, because it doesn’t have a genre, doesn’t have a category, refuses categorization. And I think brilliant, just refuse, refuse, refuse. I love books that say “no” to literature in that sense…

Amrita Sen

Hm.

Preti Taneja

… and I hope I always make that kind of art.

Amrita Sen

Yes, absolutely. We also wanted to touch upon your newest book, Aftermath.

Preti Taneja

Okay, so Aftermath is a creative nonfiction book. It’s based on me thinking through a terrorist event I was involved in, in which a man I had taught in prison—creative writing—after he was released, he went on to commit an atrocity in which two people were killed, one of whom I, I knew very well, who I worked with. So, I was in the centre of this event in a very strange way, in my own sense. And there were many centres. And of course, the real grief belongs to the families of the victims and the people who died. But because I taught creative writing to this person, because he was British-Pakistani, I’m British Asian, Indian, we have a shared South Asian origin history in Partition and Empire. And both of us were born in this country, he was a little bit younger than me. So, having that relationality, in the context of the UK, brings with it to me a certain set of responsibilities about how to think through grief, how to think through atrocity, and how to understand, again, these kind of structures of power that keep us incarcerated: immigration, poverty, austerity, the Tory policies that have marked the last two decades in this country. And “Tory” shorthand for Conservative.

So, Aftermath uses a lot of the same strategies as We That Are Young. It uses a political intertextuality. It’s woven through the sentence level with poetry from abolition poetics, from Faiz Ahmed Faiz, from resistance fighters, Joy James, all sorts of places; who, people who have come before me who’ve thought through prisons, state violence, individual violence, and thought about this idea of what “radical” means. So, for me to actually make that work was a kind of way of thinking through what happened in my position to it. Then I have to think as well about the literary life, and literary culture, and literary culture’s role in creating a divided society. If we read, therefore, we must find empathy through the characters. If we write, therefore, there must be something about us that’s inherently good. If you teach Shakespeare to a man in prison, and he writes a story, is he on his way to redemption? These are very pervasive myths, and they’re bullshit. So, the book really looks at what is behind some of those ideas. What kind of saviourism, hero narratives—fundamental mythic structures—are behind some of those ideas.

Aftermath by Preti Taneja (Transit Books, 2021)

Then in the third section of the book, I look at a few different novels and short stories of very popular that have dealt with terrorism and police and Islamophobia, and prison. And I contrast those with my experience of teaching men who were incarcerated in high security for three years. “High security” obviously means Category A crimes, including terrorism. One of the books I look at as Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed, which is The Tempest, and it’s set in a medium-security prison in Canada, where the Prospero figure, Felix, goes into this medium-security prison to teach “a bunch of Calibans”—her words, not mine—Shakespeare, and perform a version of The Tempest inside the prison. It’s a really interesting book to look at in this context of white saviourism and racial injustice and the ways in which the school-to-prison pipeline works. And I’m also bringing this back to the UK all the time because I grew up here and it’s the context I know the best. And the race elements in that as well. Because I think literary culture has a lot to answer for. The ways in which these stories get written, who gets to speak, how they get to speak, the reach they have when they speak, is something that as writers and critics we should be thinking about. That’s the way in which Shakespeare really appears in Aftermath.

Amrita Sen

And looking ahead to your future writing projects, can we expect to find more of Shakespeare?

Preti Taneja

[laughs] Possibly not directly. I’m not working on a Shakespeare trilogy of my own. But I don’t think that what I’ve learned from the language, and the poetry, and the structure of polyphony and the ways they think about dramatic themes, which are obviously inspired and inflected and infused with Shakespeare will ever go away. So, can I talk a little bit more about the unearned access that Shakespeare has? This is a really big subject, which I alluded to a little bit earlier. So, on the one hand, there’s the undeniable fact of the beauty of the poetry and the language and the sophistication of thought and theme and human feeling in the plays and in the sonnets. Undeniable. Then there’s the question of dissemination, which happens through colonialism. Then there’s an earlier question of how, how come Shakespeare in his own time became Shakespeare, so that he was the one they took on the boat to take him to India and all the colonies, right? [laughs]

So, news historians, and historians, and Shakespeare scholars, and early modern scholars are thinking about that question: who did this guy elbow out of the way? What culture perpetrated the myth of Shakespeare in Shakespeare’s time? But we all know that, you know that in our own literary culture, the market gets behind a select bunch of people. But that doesn’t mean that those who are not selected are no good. So, we don’t know what we’ve lost. We don’t know from that period of the sixteenth, seventeenth century, eighteenth century, who else we could have heard from, by the time we got to the twentieth or twenty-first century because that was decided for us before we were even imagined. And yet, Empire made sure that that particular set of works reached all the corners of where the sun never sets. We could call that unearned access. Indian Shakespeareans, Indian poets of all different Indian languages, took that work and they did what they wanted to with it. And they did what they needed to with it politically and artistically. And that gives it a richness and an afterlife that no one can control anymore. Nor should it be controlled.

Amrita Sen

Right. Thank you, thank you so much.

Conclusion

Amrita Dhar

If you enjoyed this conversation, please subscribe to this podcast, spread the word, and leave a review. Do take a look also at our project website at shakespearepostcolonies.osu.edu for materials supplementing this conversation and for further project details. Thank you for listening, and until next time, for the Shakespeare in the “Post”Colonies Project, I am Amrita Dhar.