[Professorial Lecture series post eight]

“Digital scholarship is the use of digital evidence and method, digital authoring, digital publishing, digital curation and preservation, and digital use and reuse of scholarship” – Abby Smith Rumsey.

Digital Scholarship include activities such as writing, research, and communications that take advantage of technologies in the digital world. While digital scholarship might be found everywhere from Twitter to Tumblr to WordPress, it most frequently centers around the development of scholarly works. I can say with a high level of confidence that everyone reading this post has used some form digital scholarship within the past 48 hours. If you don’t think you have. Look at what you are reading.

One can argue that any young scholar entering our profession cannot hope for a successful career without embracing digital technologies and engaging in digital scholarship. Digital scholarship is opening up a world in which in more forms of communication that use richer media, permitting easier, faster and deeper interpretation of the information.

The ability to generate and analyze unprecedented amounts of data has significantly changed many areas of scientific research. Such data sets are becoming a significant part of the scholarly record and are being published in repositories such as The Dataverse Network so that scholars can use, find and manage them as easily as journal articles and books.

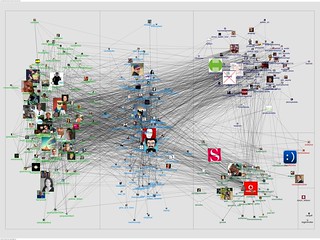

The use of interactive diagrams or multimedia such as images and videos that show procedures, sound recordings, presentational materials, and other forms of media still on the horizon can help facilitate the understanding of complex concepts. Multimedia can be used so that data can be observed in action rather than simply reported. In this sense digital scholarship is more than just using information and communication technologies to research, teach and collaborate. When taken together, the current networked environment has opened up exciting opportunities for new kinds of data-and information-intensive, distributed, collaborative, interdisciplinary scholarship.

Digital scholarship requires us to yet again to come up with new metrics in an attempt to more fully capture the influence of scholarly work. For instance, the Public Library of Science publishes a variety of metrics for each of their publications including article usage statistics (page views), comments, and blog posts citing published articles. Such metrics may help scholars gain a firm understanding of the impact of their scholarship and outreach, provide transparency to the research community and allow richer depictions of a scholar’s influence and impact.

Digital scholarship can only have meaning if it also represents a break in scholarship practices brought about through the possibilities enabled in new technologies. A 2012 survey by Ithaka S&R notes that even though “digital practices may influence these scholars’ work in a variety of ways,” few scholars see “the value of integrating digital practices into their work as a deliberate activity.” Some scholars commented that using digital methods would simply “not be worth the time. ” Even about one-third of the respondents stated that they do not know “how to effectively integrate digital research activities and methodologies” into their research and scholarship and have no desire to learn.

As Martin Weller notes in the Digital Scholar:

“Academic research is in a strange position where new entrants (researchers) are encouraged to be conservative while the reinterpretation of practice and exploration is left to established practitioners… This should be an area of concern for academia if its established practice is reducing the effectiveness of one of its most valuable inputs, namely the new researcher.”

[ Next: Scholarly Communication: The Future ]