Written by Jakob Miller

Back in 2012, something weird happened during the presidential primaries. It was quite a bit like the primary season we’re going through now — fewer candidates, but the same jockeying for position. Nothing odd there.

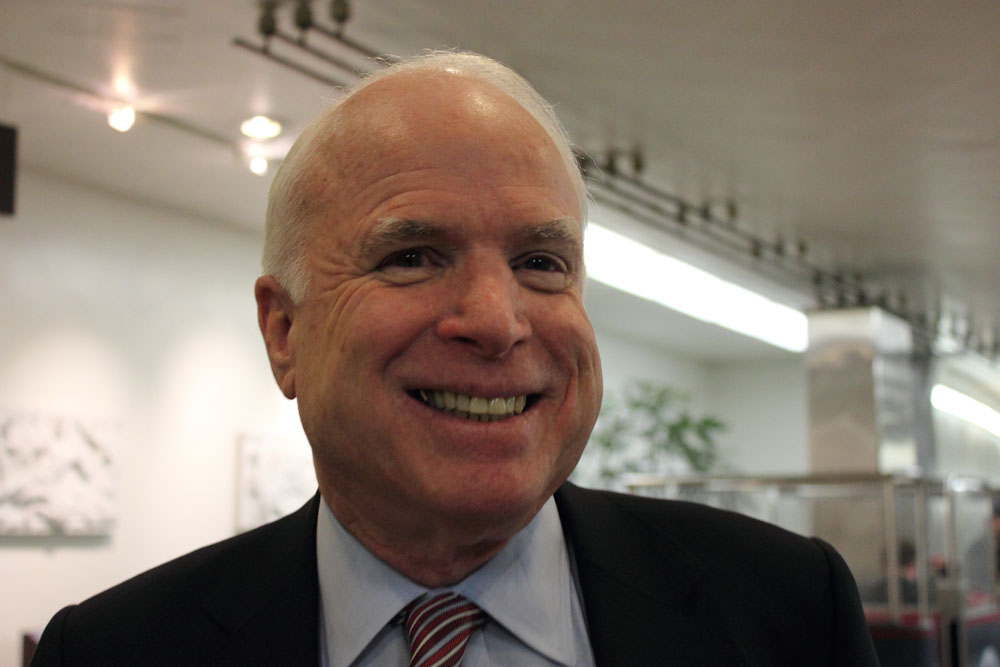

No, the odd thing was who was supporting who. The doves in the Republican party — the anti-war camp, that is — were largely backing John McCain.

Photo by Medill DC. (CC BY 2.0)

Now, if you’re familiar with Senator McCain, you’re probably quite puzzled at hearing that. If you aren’t, then McCain’s position can perhaps best be summed up by the fact that at the time he was criticizing the Pentagon for not asking for enough soldiers. He was going to send more tanks than they even wanted. A gung-ho hawk, in other words.

So why would anti-war folks back a heavily pro-war candidate? It’s not a one-off mistake. Norpoth and Perkins1 point out that when Eugene McCarthy ran for President in 1968, for example, he somehow got the support of those in favor of the Vietnam War — despite being against it himself.

Instead, it all starts to become clear if you think of people like Frankenstein’s Monster.

Photo by ICH. (CC BY 2.0)

Frankenstein’s monster can’t form complicated opinions, just an object and a level of satisfaction. So “FIRE…BAD!” is about the limit there.

The American voting public is about the same. “TAXES BAD! FLAG GOOD!” So if you’re a dove in the Republican Party and John McCain starts criticizing the way the war is being run, you’re thinking “WAR BAD” and he’s saying “WAR BAD”. The actual content of his criticism — that the current war is bad because we aren’t sending enough troops — never makes it across.

Imagine the sum total of all those unsophisticated opinions — this is the zombie army version of the Frankenstein’s monster model, if you like. So we take all the demands for conservative policies (“TAX CUTS GOOD, MILITARY CUTS BAD”, etc.) and we get a general sense of the public’s policy mood: the degree to which the hordes of American voters are droning “CONSERVATIVE GOOD” or what have you.

When you change the temperature on your thermostat, you don’t have a complicated opinion either. It’s too hot or too cold, and you give the knob a twist in the appropriate direction and wait to see how you feel. Repeat that pattern until some acceptable temperature is achieved. The public treats voting the same way: Things feel too liberal out there? That making you mad? Throw a Republican into office and see how you feel now!

Now, this style of voting is not exactly the democratic ideal. The public isn’t sitting and weighing the costs and benefits of one candidate’s policy platform against the others. They might not have any idea what either candidate’s position actually is: but that McCain guy’s mad, and I’m mad, and that’s good enough for me!

You can see this in our current voting cycle as well! We currently have two outsider candidates doing far better than anyone predicted.

Photo by Chicago Tribune, used under Fair Use.

Photo by Chicago Tribune, used under Fair Use.

Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump are definitely from opposite sides of the aisle – and that’s what makes it odd when voters say things like this:

Daniel Nadeau, 22, of St. Albans, Vt., said of Mr. Trump. “Bernie is my No. 1 choice, and Trump is No. 2. They’re not that different.” New York Times.

They may be bitterly opposed ideologically: but Bernie and the Donald are both angry. They both give voice to pent up political frustrations. And for a lot of Americans, that’s good enough.

Now, if you’re cynical enough that that doesn’t surprise or bother you:

- Congratulations on your future career in politics! And..

- Consider the implications.

If you’re in an elected office, conventional wisdom would say that you should deliver. If you got in because the public was in the mood for more liberal policy, you had better come up with some liberal reforms if you want to keep your seat.

Buuuuut… If you only got elected because the public was hungry for change, then it’s in your best interest to keep them hungry. If you actually go around delivering on your campaign promises, you’d reduce the public’s demand for liberal policy. All those angry zombies that got you into office would quiet down, and you’d have handed the advantage over to your conservative competitor come reelection time as his zombies get all fired up.2 If the public was paying attention to the details of what you actually did, and rewarding you appropriately, then there wouldn’t be a problem: but ![]() .

.

America is like a country with a broken thermostat — when we turn the heat up, the furnace has a vested interest in keeping the house cold because of how much it hates the air conditioner. So the next time a politician gets under your skin for not keeping their campaign promises, consider this: would you do any better?