This project is a presentation of media and text to present the significance of Andean Indigenous Women Leaders in the 21st century. In the Andean pre-colonial era, women played a relevant role in society, often becoming leaders over their tribes, chiefdom, or larger groups. In the colonial era after the arrival of the Spanish, and the implementation of their new code of laws, indigenous people and women in particular lost power and control in their society. A new power of inheritance was introduced that displaced the traditional Andean system. This system allowed women to maintain some economic control of power but marginalized their political power. When the independence against the Spanish began in the 19th century, life for the indigenous people in the region changed dramatically. Many fought in the independence wars and contributed to the war effort. But in the end did not receive the promises that they believed they would earn for the their efforts. Life in this post-colonial era became much more difficult for the indigenous people. They were constantly viewed as bottom class of society, and a problem by the creole elites. The communal lands, lands shared by indigenous communities, were privatized, broken up, and sold to larger land holders. This forced many indigenous peoples to relocated and create new lives for themselves often becoming tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and migrant workers. Life was hard for most indigenous communities in the 20th century. Andean governments did little to improve the conditions of these communities. Indigenous women’s lives were mostly influenced by local governors, judges, and priests. The endured much abuse from these groups. During the 20th Century life among indigenous women improved, but they did little to move forward in politics and education, these conditions would improve in the later part of the 20th century. Though indigenous women did move more into the cities. Many of the younger women took on domestic jobs in urban life. Others became mediators and more independent and entrepreneurial in local markets. In the latter part of the century things began to change. Indigenous people and women became more active in politics and pushing for their rights. Women like Dolores Cacuango, Nina Pacari, Paulina Arpasi Velasquez, Remedios Loza and Isabel Ortega became influential Andean indigenous women leaders in late 20th century and early 21st century. These women some still revelant and active in politics today are shaping a new post-neo-liberal political landscape in the countries of the Andes.

Source: Smith, Bonnie G. “Andean Groups since 1500 C.E.” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford, England: Oxford UP, 2008. 563-67. Print.

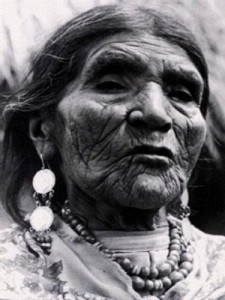

Above is Dolores Cacuango, an Indigenous women from Ecuador, who in the 20th century became in influential figure in the Indigenous rights movement. She escaped from a hacienda at a young age and was unmarried. At this time she spoke little Spanish, but spoke her native Quechua. She would eventually learn to speak Spanish and used it to challenge the state, and the cultural ways of indigenous and non-indigenous Andean people. She went to major cities in the Andean region, challenging the ways in which native peoples were represented. In 1931 she, along with Jesus Gualavisi, organized an indigenous strike against haciendas in the region of Cayambe, and were arrested for attempting to organize a country wide indigenous meeting. She was a communist activist, and wanted equality for all, but did so in a way that captured the struggles of people in her region against the state. In 1945 she along with other political activists formed the FEI or Federation of Ecuadorian Indians, the first political organization in Ecuador for Indigenous people. She became the secretary-general of the organization. This organization would eventually help the indigenous earn reform laws that benefited the people. She wanted to create a positive image of her people, which for so long had been viewed culturally in a negative way. She was a profound speaker and could connect the political environment around her in a way that everyday people could understand. Her voice became one that indigenous people could recognize and identify with. Although she did not live into the 21st century she laid the foreground for Andean women, and the leaders that succeeded her.

Sources: Baud, Michiel, and Rosanne Rutten. Popular Intellectuals and Social Movements: Framing Protest in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004. 62-63. Print.

Gutiérrez, Natividad. Women, Ethnicity, and Nationalisms in Latin America. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate Pub., 2007. Print.

Ross, Clif, Marcy Rein, and Raúl Zibechi. Until the Rulers Obey: Voices from Latin American Social Movements. Oakland, CA: PM, 2014. 213. Print.

This is Nina Pacari, a modern 21st century Ecuadorian indigenous female leader. She was born Maria Estela Vega Cornejo, in an urban town in northern highlands. She changed her name to Nina Pacari, which translated from Quechua means “fire dawn.” It is a symbol of ethnic pride, and expresses her envisioned future for ethnically Andean people. She grew up in between two different worlds, separated from rural communities and isolated from the predominantly Mestizo people that she lived among. She faced a lot of racism being in this state. But this eventually helped her gain a sense of ethnic pride. She would eventually move forward and attend college in Quito. During this time in her life she said the racism was worse in the big city. She was not allowed to enter restaurants, pools, and hotels just for being Indian. But this did not stop her from holding her pride. She eventually graduated as a lawyer from University. Then she set up practice and became more interested in the ethnic movement. She joined the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, becoming a legal adviser for them. She was the first women to hold this position. Her job was to administer land and territory. She would alter become one of the founding members of Pachakutik, holding the same position there. Eventually her new party allied with military party of Lucio Gutierrez, who would become president of Ecuador. During his presidency, Pacari was appointed to be the minister of foreign affairs. She also became the first Ecuadorian women elected to Ecuador’s National Assembly. She would resign from her post because of political disagreements with Gutierrez, and she did not want to compromise goals of creating a purli-national state. She helped organize street protests through her indigenous political organizations. She has become an influential Indigenous women leader from Andean. Her success shows there is a growing indigenous pride in South America and an overcoming of adversity and racism.

Sources: Stahler-Sholk, Richard, Glen David. Kuecker, and Harry E. Vanden. Latin American Social Movements in the Twenty-first Century: Resistance, Power, and Democracy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. Print.

Torre, Carlos De La, and Steve Striffler. The Ecuador Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Durham: Duke UP, 2008. Print.

This is Paulina Arpasi Velasquez. She is a modern day congresswoman from Peru and Aymara women from Puno. She was elected to parliament in 2000. She is known for dressing in traditional Aymara outfits with pride. She promotes indigenous rights and believes there is not enough political participation from civil society. She wants to promote more participation of the people in government. She believes that their would be less protests and marches in the street if people participated and had dialogues within the government. She is one of the few Indigenous female participants in the Peruvian government. She is challenging the history of a male and Creole dominated Peruvian government. She is opening the doors for further indigenous women participating government in Peru, creating a more equal society in terms of gender relationships and political activism.

Sources: Smith, Bonnie G. “Andean Groups since 1500 C.E.” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford, England: Oxford UP, 2008. 564. Print.

McNulty, Stephanie L. Voice and Vote: Decentralization and Participation in Post-Fujimori Peru. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2011. Print.

This is Remedios Loza, she was born the city of La Paz in Bolivia in the mid-twentieth century. She became popular among Bolivians through her appearances on radio and television. She got this start by working with Carlos Palenque on his radio show. She became involved with the CONDEPA political party. In 1989 CONDEPA had successful performance in the elections and won several seats in congress. Palenque the head of the party appointed his co-host on his radio program Remedios Loza to one of these seats. Through popular vote she became a senator within the republic. In 1997 she became the first indigenous women presidential candidate in Bolivia. Of the major candidates she was the only one with an indigenous and populist background. In the elections she would finish fourth, one in which the indigenous voice was poorly represented, even though she was an indigenous candidate running. Incumbent Hugo Banzer would maintain his status and win the election. Remedios would retire from politics in 2002. But her influence is no less felt. Her legacy and strides she made in politics helped legitimize indigenous people and women involved in politics, in country that had little political activism among indigenous women its history. In 2006 Evo Morales become the first indigenous person elected to the presidency in Bolivia. Her push in the 1997 to try and become the first indigenous president in her country helped influence and allow for Evo Morales to accomplish this goal and help push new rights, protections, and opportunities for ethnically indigenous Andean peoples.

Sources: Morales, Waltraud Q. A Brief History of Bolivia. New York: Facts On File, 2003. 221-222 Print.