WHAT IS THE PANCREAS?

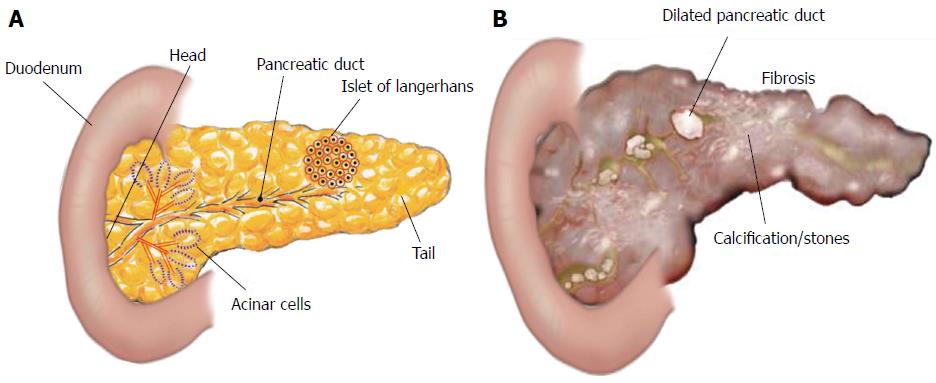

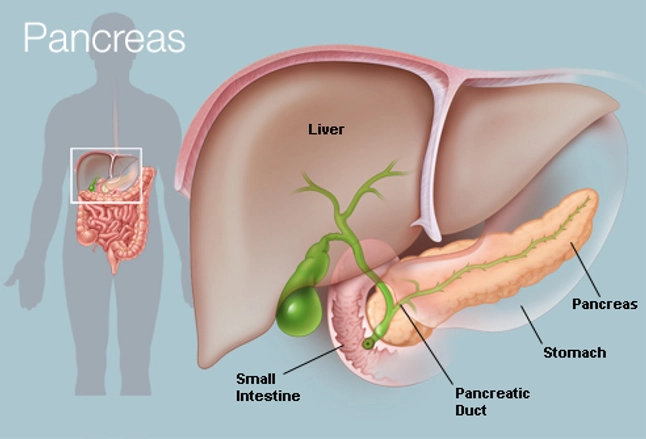

The pancreas is one of our body’s vital organs. The pancreas is located behind the stomach, and it is connected to the rest of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract via the pancreatic duct (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 656). The pancreas functions as an endocrine and exocrine gland. The function of the exocrine pancreas is to secrete enzymes and alkaline fluids that aid in the digestion of meals (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1312). The function of the endocrine pancreas is to produce hormones that help our bodies use the energy from food (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 656-658).

(Hoffman, 2018)

(What is pancreatic cancer?, n.d.)

The pancreas is composed of 5 main sections: the tail, the body, the neck, the head and the uncinate process (Ellis, 2007). Within the pancreas, there are multiple ducts including the pancreatic duct, the common bile duct, and the accessory pancreatic duct. These ducts enable different enzymes and hormones to enter the gastrointestinal tract and the bloodstream (McCance & Huether, 2019, p.657).

(The pancreas, n.d.)

HOW DOES THE PANCREAS WORK?

ENDOCRINE PANCREAS

The pancreas releases hormones via endocrine glands directly into the bloodstream. The hormone secreting cells in the pancreas reside within the Islets of Langerhans, and they include the alpha cells, beta cells, delta cells, and F (also known as PP) cells. Alpha cells stimulate glucagon, a hormone that stimulates the liver to breakdown glycogen. Glycogen is our body’s glucose reserve, primarily stored in the liver. As this is broken down, it increases our blood glucose. Glucagon can also stimulate the body to break down fat and to stop the release of insulin. Both of these processes also increase blood glucose levels. Glucagon release is chiefly controlled by blood glucose levels, with inhibition occurring with high blood sugar and activation with low blood sugar. Beta cells secrete insulin and amylin. Insulin is a hormone that functions to control blood glucose levels by regulating the uptake of glucose into cells. Insulin release is regulated by the parasympathetic nervous system prior to food consumption. It is also regulated by the blood glucose level, the presence of amino acids within the blood, and alterations in other GI hormone levels. Amylin is a hormone that is secreted with insulin and functions to control the blood glucose level. Amylin regulates the blood glucose level indirectly by controlling the pace of gastric emptying and aiding in the inhibition of glucagon after eating. The F (PP) cells release pancreatic polypeptide, which is a hormone controlled by the blood glucose levels and the presence of amino acids. This hormone results in an increase in gastric secretions and blocks the action of cholecystokinin, a hormone that stimulates the breakdown of fat and protein. The delta cells secrete pancreatic somatostatin as well as gastrin. Pancreatic somatostatin functions to control the actions of both alpha and beta cells within the pancreas in response to blood glucose levels. The action of the pancreatic somatostatin on those cells leads to the inhibition of the hormones they release such as insulin, glucagon, and pancreatic polypeptide. The hormone that is inhibited is determined by the blood glucose level. Gastrin functions to increase the release of gastric acid and promote the digestion of proteins (McCance & Huether, 2019, p.656-658).

EXOCRINE PANCREAS

The exocrine pancreas is made up of acinar cells and a complex duct system. Acinar cells are arranged in acini, which are spherical groups surrounding a secretory duct. The function of the acinar cells is to release enzymes that are involved in digestion of nutrients. The enzymes released by the exocrine pancreas include proteases, amylases, and lipases. Proteases are enzymes that break down proteins, and they include trypsin, carboxypeptidase, elastase, and chymotrypsin. Proteolytic enzymes are released as inactive enzymes, and this occurs to protect the pancreas from self-digestion. The proteolytic enzymes are activated within the duodenum so that they can break down proteins during digestion. Amylases are enzymes that are responsible for breaking down carbohydrates into glucose. They include pancreatic alpha-amylase, which is released already activated into the duodenum. Lipases are enzymes that break down fats into fatty-acids. This action occurs via the breakdown of triglycerides, phospholipids, and cholesterol. The pancreas’ duct system is responsible for releasing alkaline, or pH basic, fluids via the ductal cells. This alkaline fluid is primarily composed of bicarbonate, which aids in neutralizing acids. The fluid’s function is to dilute pancreatic juice so that the correct pH needed for digestion is obtained. The two main ducts within the pancreas are the pancreatic duct (i.e. Wirsung duct) and common bile duct. Some individuals may also have an accessory pancreatic duct (i.e. Santorini duct) that can release the alkaline fluid/enzymes directly into the duodenum. The smaller secretory ducts drain into the pancreatic duct, which connects to the common bile duct at the ampulla of Vater. The common bile duct will drain all of the fluids/enzymes into the duodenum (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1312-1314).

(Function of the pancreas, n.d.)

WHAT IS PANCREATITIS?

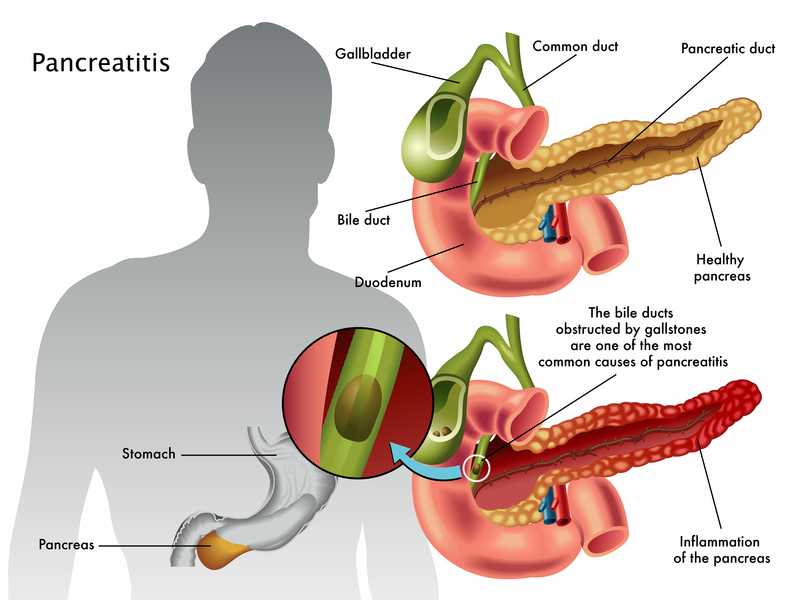

Pancreatitis is a pathological disorder in which the pancreas becomes inflamed. The condition’s incidence does not vary among genders, but it does tend to increase in age with an average onset at 50-60 years old. Pancreatitis can be chronic or acute, and may be life threatening in some cases. There are risk factors for developing pancreatitis including excessive alcohol intake, dyslipidemia, smoking, development of peptic ulcers, trauma to the abdomen, genetics, and obstructive biliary tract disease (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1354).

ACUTE PANCREATITIS

Acute pancreatitis is most commonly caused by a blockage within either the bile duct or the pancreatic duct that leads to a buildup of pancreatic enzymes within the pancreas. The disease may also be caused by drugs or an infection, typically viral in nature. For most cases, acute pancreatitis is fairly mild and resolves on its own. However, there are cases that will require hospitalization. Since the exocrine pancreas releases digestive enzymes, there is self-digestion of the pancreas when the enzymes remain trapped within the pancreas. It should be noted that under normal circumstances proteases produced within the pancreas are in the inactive state until they reach the duodenum. In an instance of a blockage, however, the pancreas is signaled to released activated enzymes to speed up the process of digestion in the duodenum. This reaction occurs because the body begins to lack nutrients due to the lack of enzymes to break down nutrients. As a result of the self-digestion, the pancreas becomes inflamed and swollen (i.e. edematous). The edema can decrease the amount of blood that reaches parts of the pancreas (i.e. ischemia) that leads to cell death (i.e. necrosis). This is a condition already occurring at the same time due to the self-digestion. In addition to the necrosis and inflammation, the pancreas may also create pseudocysts, or pockets of fluid, in an attempt to package up the enzymes and reduce further damage. In the more severe cases of acute pancreatitis, it is possible to see systemic symptoms including increased white blood cells, cytokine release, blood vessel wall damage, and issues with the ability for blood to clot. All of these systemic effects can lead to dilation of blood vessels, hypotension, and in severe cases even shock. Instances of severe pancreatitis can also lead to harmful complications such as kidney failure, infection of the abdominal lining (peritonitis), sepsis, heart failure, hypertension within the abdomen, and respiratory distress. If the inflammation within the pancreas is not resolved quickly or flares up multiple times, there can be activation of the stellate cells within the pancreas. The stellate cell activation causes fibrosis and scarring of the pancreas, thus leading into chronic pancreatitis (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1354-1355).

(Acute pancreatitis, n.d.)

CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

Chronic pancreatitis occurs when the pancreas undergoes inflammation and scarring of the tissue (i.e. fibrosis). The risk factors for chronic pancreatitis include excessive alcohol consumption and/or smoking. Chronic pancreatitis can be further classified into chronic calcifying pancreatitis, chronic duct obstructions pancreatitis, and auto-immune pancreatitis. However, it is important to recognize that 25% of chronic pancreatitis cases are idiopathic in nature (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1355).

CHRONIC CALCIFYING PANCREATITIS

The most common cause of chronic calcifying pancreatitis is chronic smoking and alcohol consumption. Both of those activities can lead to acute pancreatitis flare ups, which overtime lead to fibrosis (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1355). As the disease progresses, calcium deposits form inside the pancreatic duct and its branches. These deposits cause the pancreatic duct to distort, narrow (forming strictures), and break down (Majumder & Chari, 2016).

(Manohar, Verma, Venkateshaiah, Sanders, & Mishra, 2017)

CHRONIC DUCT OBSTRUCTION PANCREATITIS

Chronic duct obstruction pancreatitis is most commonly caused by gallstones, tumors, or trauma to the abdomen either accidentally or from procedures such as endoscopies. In this form of chronic pancreatitis, there is a great degree of fibrosis and stricture formation. The area of the pancreas impacted is related to where the obstruction occurs. The parts of the pancreas distal to the obstruction will experience the chronic pancreatitis symptoms (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1355).

(Health publishing, 2019)

(Pancreas, 2016)

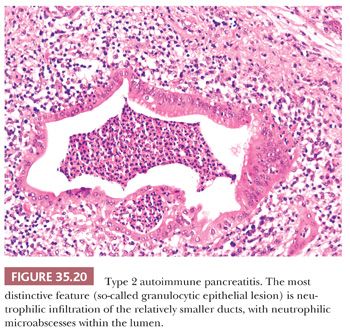

AUTOIMMUNE CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

Autoimmune chronic pancreatitis involves two subtypes: type 1 and type 2. Type 1 is also referred to as lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis. It is a disease that involves fibrosis and inflammation in multiple systems through the action of immunoglobulin G4. This type of autoimmune chronic pancreatitis causes changes to the pancreatic ducts and veins that lead to a painless form of jaundice. Type 2 is also referred to as idiopathic duct centric pancreatitis. In this form, the disease only occurs in the pancreas and involves neutrophils. The neutrophils pack into the pancreatic duct, leading to obliteration and blockage. Both type 1 and type 2 autoimmune chronic pancreatitis can be treated with corticosteroids and immunomodulators (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1355-1356).

HOW IS ACUTE PANCREATITIS DIAGNOSED?

The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis begins with a thorough medical examination and health history. The physical exam should include a pain assessment to determine the location, intensity, and quality of the pain. In acute pancreatitis, the pain will normally radiate from the upper left abdomen to the back, and may be associated with nausea and vomiting (Shah, Mourad, & Bramhall, 2018). The provider will also cross-reference previous disorders the patient may have that are considered associative disorders with pancreatitis. The provider will also need to order bloodwork and imaging such as a CT-scan and/or endoscopy. The most characteristic lab finding with acute pancreatitis is a three-fold increase in the concentration of the individual’s serum amylase, though this number alone will not be able to give information on the severity of the pancreatitis. For diagnostic purposes, however, the individual’s serum lipase will also need to be elevated at least three-fold (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1354-1355). In some individuals, the alanine aminotransferase enzyme will be elevated to over 150 IU/L (Shah et. al, 2018). In order to determine how severe the disease is, a provider may also order a C-reactive protein blood test as well as utilize a scoring system per hospital policy.

HOW IS CHRONIC PANCREATITIS DIAGNOSED?

The diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis also begins with a thorough physical examination and health history. Most individuals will report pain that may be continuous or intermittent. They may also exhibit weight loss, diabetes mellitus, deficiencies of vitamins (especially fat-soluble), overall status of malnutrition, and/or fatty streaks in stool (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1356). The provider will order imaging such as CT scans that can show evidence of atrophy and fibrosis. Other tests include looking at pancreatic function tests collected via endoscopy (Duggan et. al, 2016). It is the presence of the fibrosis, strictures, and/or atrophy that differentiates chronic pancreatitis from acute pancreatitis (McCance & Huether, 2019, p. 1354-1356; Duggan et. al, 2016).

**ADD PANCREATIC AUTO-ISLET TXP**